For three years, I boarded a bus in West Pullman, then transferred to the Red Line train to attend Chicago’s Roosevelt University. Black bodies strolled up and down train cars hawking loose squares, loud, socks, and bootleg movies. Men would lean across the aisle or sit next to me even though there were many open single seats and say, “How you doing baby girl? You got a phone number?” Other riders loathed my fat body spilling over into the seat next to me, judging me with their eyes. Occasionally, riders fought or debated whether or not a person could be born gay. I covered my ears with sound to shield myself from these things. The melodies in my headphones could not block out the churning of the bus or the train screeching along the tracks, but it could mute everything else. If I stared down at my hands, I could forget someone else was driving; it could feel like someone was tugging me along a bumpy road. This was a kind of freedom.

Like being nestled in hasty piano chords as a pitchy voice sang, “If I were any older, I could act my age. It’s not the way I’m meant to be, it’s just the way the operation made me.”

Like feeling caressed as a high-pitched nasal voice proclaimed over rolling guitars, “All alone in space and time, there’s nothing here but what here’s mine.”

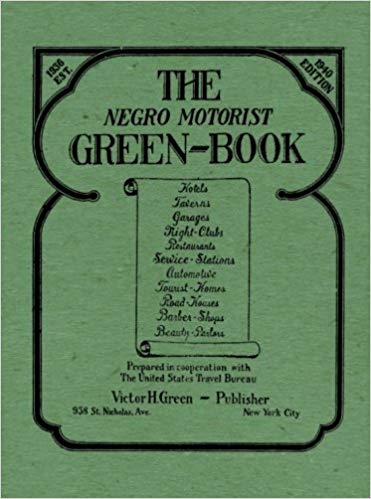

At Roosevelt, I was introduced to Victor Green’s the Negro Motorist Green Book in a class called the American Road Narrative. First published in 1937, the slim paperback book catalogued New York area businesses — six or seven to a page boxed in green — committed to regarding Black Americans and their coins with respect, not violence, in the era of Jim Crow. Its first page is a short introduction written in green ink on paper I imagine was once the color of eggshells. Now, it appears brown with age like a high school English or history project, tea-stained for historic accuracy. On a page titled “Preparedness,” Victor Green, the book’s publisher, writes colloquially — like an uncle delivering loving advice in his appeal to the Negro motorist — explicitly urging them to protect their cars, not their bodies.

“Nothing is more of a killjoy when the motor starts to spit and pop and then stops. To overcome this and add comfort and uninterrupted pleasure; everything should be done to prevent these enforced halts,” Green warns. “A motor tune-up is the solution. This checkup, when done properly, will remove the hidden evils, and will allow your motor to perform at its maximum efficiency.” But the Black reader of the day knew this was doublespeak. When Green warned about the “enforced halts” and “hidden evils” of a faulty motor, he was also talking about the violent evils lurking in racist restaurants, hotels, attractions, and white motorists in New York City. Consulting this book before any trip to New York was the checkup needed to ensure “comfort and uninterrupted pleasure.”

The warm hug of Green’s casual language, the soothing caress up and down the back as the warning is delivered, is another talk.

Like the episode of Blackish where Ruby is warning her toddler, teenaged, and adult son, Dre, that, “America hates you,” in the same cadence and conviction that you might say, “I love you. I want you to be safe.”

Like that episode of Scandal where Olivia and her father stand in an airport hangar. He is urging her to repeat the mantra that has looped in her mind in his quick, reverent tone since childhood: “You have to be twice as good as them to get half of what they have!” There is harshness in those words but love reverberates through them. Her father seems to say, “You are not afforded the ease of latitude your white peers enjoy. You need to seize every opportunity for mobility afforded to you. Then, when those opportunities are exhausted, create your own so you can be successful.” Once, my own father gave me a talk about road travel.

One morning in early May, I stood on my grandmother’s porch and watched my father as he leaned next to his car, his nose nearly touching his phone screen. He wore a pair of black trousers that begged to be hemmed, slimmed out in the thigh, and taken in at the waist. His white collared shirt looked as though it had been trampled. This look could not be saved, but a black leather loafer might have at least improved it. Instead, the overly long hem of his trousers was stuffed into the tongue of black and purple Shaq’s from Payless. RIP Payless.

Once my grandmother said her travel prayer — the one she said no matter how far or how close her destination, no matter if she was the driver or the passenger — she appeared on the porch. Her salt and pepper hair was hidden under her church-and-special-occasion wig — a jet black shoulder-length bob. Her body was clad in a robin’s egg blue skirt suit.

As we descended the stairs, my father and I exchanged greetings before I called out to him, “What are you wearing?”

“Clothes. Why?”

“You don’t wear sneakers, let alone Payless sneakers, to a function,” I replied.

“They’re just clothes. Chill out, Tiffany.”

“Ain’t no such thing as just clothes. Clothes demonstrate your intentionality, how much you care. Also, value your feet more, bruh. You must do better.”

“Girl, just get in the car. I said be ready at 8:00, it’s 8:30”

“Whatever.”

My father, my grandmother, and I loaded into his ash gray Neon — a tiny little thing that was his ex-wife’s in the late 1990s — to attend my graduation from Roosevelt University.

As my father drove, he talked at my grandmother, Mommy Mae, in his high-pitched lisp while she rode along in the passenger seat. She listened to him, or at least pretended to, her “mmmhmms” and “uh huhs” placed perfectly. I sat in the back seat.

Midway into our journey to Downtown Chicago, we hit mild traffic. Not the kind that confines you to a small stretch of road for several minutes before traffic moves briefly and you find yourself confined yet again. We moved steadily, but slower than my father’s usual ten or fifteen miles over the speed limit.

“See this is why I told y’all to be ready at 8:00,” he said, annoyed, glancing from the road to my grandmother, never catching my eyes in the rearview mirror. “Look at all this traffic. Y’all better hope we don’t miss the whole thing.”

As the wheels rolled slowly beneath us, my father’s complaints about the traffic flowed into the backseat at a similar pace. As we inched toward our destination, my chest began to constrict, then rest, like a hand balling into a tight fist, then releasing the tension in the fingers, opening itself only to ball up again. My left arm lay against the backseat, made immobile by the heaviness of nerves. I’d spent months in therapy, debating whether I should invite my father to the graduation I’d never planned to attend, questioning if sharing his blood could soothe the hurt he inflicted the way my grandmother said it should. “He’s your father, you can’t just not talk to him,” she would say after every upset.

Mommy Mae wanted to sit in the front row of Roosevelt University’s auditorium wearing her Sunday best to watch me do what so many family members said I couldn’t do, what so many citizens of our nation said a Southside hood rat couldn’t do. What so many citizens of our nation said my grandmother couldn’t do when she was spending the daylight hours picking bulbs of cotton barefoot on a plantation in Tchula, Mississippi, instead of attending school.

When at least five of her seven children (my father included) told Mommy Mae that I was a worthless child nobody, not even my parents (my mother included) wanted, she took me into her home. This graduation was her victory lap. This woman who graduated eighth grade in a one-room schoolhouse, wearing her only pair of shoes, wanted to sit perched with a smirk while my father sat next to her and watched me receive a sliver of the knowledge she had accumulated over her 88 years.

I wanted joy for my grandmother as much as I wanted her to realize that I didn’t need just any father, I needed a father who would hold me physically and emotionally the way I needed to be held — with consideration, with care. I wanted her to know that reveling in her victory could stir in my father the harshness that led me to her home all those years ago. Still, I agreed to attend. A few months after that, I agreed to invite my father. Mommy Mae had given me so much. I gave her the only currency I had: a graduation.

“Hey, can you do me a favor and stop complaining about traffic? It’s moving, we’re moving. I’m not trying to be rude, it’s just you’re making my chest hurt, making me think we ain’t gone make it.” I did not have to yell; the backseat was so close to the front I could have whispered in his ear. “Since it’s your day I’mma’ let you have this one! This is what people do when they drive, Tiffany! They complain about traffic!” my father replied.

I was surprised by such a benign response, but only momentarily.

47th St.: “You know, you need to learn some respect. This is my car.”

35th St.: “This is why my family don’t fuck with you now. You so disrespectful, always running your damn mouth. You should be working anyway, not be twenty-five and just graduating college.”

Cermak/Chinatown: “I’ll put your fat ass out my fucking car! I don’t care if we are on the Goddamn expressway!”

Lake Shore Drive: “I’ll beat your fucking ass, bitch! Who the fuck do you think you talking to?”

As my father navigated the crowded downtown streets, the police detector suctioned to his windshield beeped fast and loud like a scream to alert us of a nearing CPD vehicle. I shrank deeper and deeper into myself. There was horror inside. There was horror outside.

I wanted to encase myself in 80 beats per minute and above, sounds faster than the car could move in traffic. If I had taken the train, I could have adorned my ears with headphones and settled into the bumps forward as we moved downtown and the lurches backward as the train came to a stop. Exiting the subway there could have been the assuredness of ground underfoot — a pleasure greater than that of buses and trains. The comfort that only I could propel myself forward. Seconds later the ash grey neon pulled up in front of the school. “I know what the fucking problem is, what the problem really is,” my father said, turning toward me, so close I could feel his spit sprinkle the tip of my nose. “You need to grow your ass up and learn how to drive.”

He seemed to say, “You need to seize every opportunity for mobility afforded to you. Then, when those opportunities are exhausted, create your own so you can be successful.” Like Olivia’s father, I imagine he knew the crudeness in his words but could not help himself. “If you could drive, you could have protected yourself from me,” I thought I heard him say. I imagine Olivia’s father felt that if she hadn’t forgotten the implications of the color of her skin, she could have been spared his manipulative intrusions.

Still, at that moment, all of my accomplishments and failures seemed to collapse neatly into one phrase: You are twenty-five and you can’t drive.

Like in Clueless when Tai tells Cher, “I don’t know why I’m listening to you anyway! You’re a virgin who can’t drive.”

Chicago’s transit system can take you anywhere, but living out South, where the overwhelming majority of the city’s Black population is housed, amenities and necessities like shopping centers, restaurants, and entertainment are often not within walking distance. From my grandmother’s house in West Pullman, I could travel Downtown or up North on public transportation with relative ease. Still, on the Southside, public transportation to an address a fifteen-minute drive away from my grandmother’s home could take as many as three buses. On days where I could not bring myself to make those cumbersome trips, I would ask my aunt or a friend for a ride. In some cases, the answer was no. If the answer was yes, I curated the music, became the GPS, cracked jokes, anything to keep myself in the driver’s good graces. When I failed, the ride was overtaken by the driver’s distaste for my asking this favor or commentary about how grateful I should be that they were willing to grant me this kind of movement.

Like so many people saying, “How do you, like, do anything if you can’t drive?”

Like men who wanted to have sex with me taking pleasure in saying some variation of, “Anything you don’t know, I’ll teach you,” after learning I could not drive.

Like my teacher’s curled lip as he said, “You can’t drive? That’s crazy. But, like, you love music so much. Songs gon’ sound so different when you can drive.”

Like the love interest who drove around my grandmother’s block jerking his shoulders back and forth while blasting, “Meet me in the trap, it’s goin’ down.”

“This song was cute for like eight seconds in the early 2000s,” I said.

I sat in the passenger seat. My hands covered my face in an attempt to hide my nervous laughter. The bass boomed so loud he could not hear my chuckles. I was embarrassed — not for myself, but for his poor music selection after a string of otherwise solid choices.

“This song still goes,” he said, rounding the block a second time. “You just never heard it while you were moving like this.”

I was never one of those teenagers holding a fresh driving permit, asking my parents if every family car trip could become an opportunity to practice my driving skills. That is a rite of passage I didn’t experience. Permit carrying teenagers — the driving initiated — soon became adults driving to their full-time jobs and picking their children up from school before retiring to their homes for the evening. Homes in cities and rural areas we now call the suburbs, places where human lives were devastated to ensure cars had enough space to move and rest. In some places, Black neighborhoods in urban city centers were demolished to build expressways as a solution to the traffic that increased along with the boom in car ownership, and a cure for the fear white folks held of living near large Black populations confined to small spaces.

But white fear never dissipates, it only transfers. As those displaced Black families spread across cities, many of them moving into white neighborhoods, white folks gathered their things (seemingly overnight) and moved to new, more affluent suburbs where, because of the new expressways, they could travel to the city for the day before returning home to a place where, because of loan and job discrimination, Black people could not live. Now, parking lots take up a quarter of all available land in some cities, expanses of land that could be used to house displaced Black families or create affordable housing for poor people of color. This history is a central part of that rite of passage.

Driving became an important rite of passage for Black Americans when — physically and mentally worn — they took to the road. A historian in the documentary Driving While Black proclaimed that in the 1930s, “If you are African American and you can afford a car, even if it’s a used car, it provides a powerful alternative to the daily indignities of riding the rails, of riding the streetcar, of riding the bus.” As he speaks, a black and white image of a Black man in a three-piece suit appears on the screen. The man stands proudly next to a car in 1934. The car and its shiny rims are a symbol of abundance. Not just financial abundance, but the abundance of possibility. Now, after being confined to tight spaces for so long, Black folks could load Blackness, with its rich regional cultures, into a car and transport it across the interstate, exchanging cultures and sharing similarities with Black folks across the country. The ability to experience other Black lives in other places meant experiencing what was possible. In his crisp, starched suit, this Black man takes pride in that promise.

Like a Chicago accent with southern edges painting us this picture: “Plus, he had the spinner from his Daytons in his hand. Keys in his hand, reason again to let you know he’s the man.” Like the bling era of the late 1990s and early 2000s. Boast had long been a hallmark of a hot sixteen, but when rapping about the diamonds on their twenty-inch rims, the Cash Money Millionaires wanted you to know that this group of men from New Orleans’ Magnolia Projects were no longer confined and could whip candy-painted cars to experience other possibilities. These men adorned their cars with Lorenzo rims, Yokahama tires, and animal skin on the interiors to honor the symbol of possibility that allowed them to momentarily grip their fate between their hands as they rode.

Like a New Orleans accent light on the “R’s” rapping, “Alligator seats with the head in the inside/swine on the dash, G-wagon is So Fly,” to a melody like a lullaby.

In Driving While Black, there is an image of another woman sitting in the back seat of a car, her lips a straight line of neither glee nor despair. “You have control over where you sit. You aren’t being supervised by bus conductors, train conductors,” the historian says. “You don’t have to defer to whites in ways that are really dehumanizing when you’re traveling by car. So, there’s a way in which being behind the wheel gives African Americans a degree of freedom, a degree of immunity from the slings and arrows of Jim Crow on a daily basis. … Many long-distance Black travelers traveled at night because the police regularly targeted African American drivers, leading some to decide to travel at night, so they aren’t as easily seen. During the day, African Americans could be spotted much more easily by cops and were disproportionately targeted for what would later come to be known as driving while Black.”

The man and woman in Driving While Black’s images could have been two of many Black grannies and aunties, Black granddaddies and uncles who piled into cars in Alabama, Mississippi, and Arkansas and drove to Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles during the Great Migration. These Black folks seeking political asylum were hardly reported by most media outlets between 1916 and 1950, when the movement was at its height. The Chicago Defender, however, ran opinion and reported articles about the arbitrary lynch mobs and other violent acts taking place — though not exclusively — in the Southern United States. The headline of one paper simply read, “The Exodus.” As Black folks were fleeing the South, hoping to experience “a degree of freedom,” Victor Green’s Green Book reminded them how small of a measurement a degree was. These freedoms were only momentary.

In 1944, Mommy Mae was one of the Black grannies and aunties that took the train from Tchula to Chicago during the Great Migration. The same sure footing that moved her down rows of Mississppi cotton moved her across Chicago’s Northside where she lived and cleaned the homes of white families. In the Alged Gardens Housing Project, her feet carried her to the macaroni factory where she worked and back home where she nutured seven children. Later, those feet carried her to my preschool where she picked me up if my parents were working. I leaped into her arms, thinking that she could do anything. Even though she didn’t roll on four wheels, Mommy Mae was never lacking. She lived in Chicago for thirty years before the urge to drive overcame her.

“I got tired of begging folks to take me places it was hard to walk or take the bus to,” she told me. “If I could get them to take me, they would act like they didn’t want to go the whole time. Then, when we got to where we were going, they would rush me.”

My father would like you to believe that he taught my grandmother to drive with patience, that he gently instructed her through two-point turns and parallel parking. Her version of the story differs. In her version, my grandfather and father taught her to drive, yelling from the passenger seat if her turns were too wide or too narrow, threatening to cease lessons if she parked too far from or too close to the curb. More than thirty minutes on the road and my grandmother’s stomach lurched with every bump, stirred as she felt the wheels gliding over smooth stretches of road. Still, she drove herself (and occasionally me) everywhere until she could no longer drive at night. Then, in her early eighties, cataracts overtook her eyes and her license was revoked.

My grandmother never read The Green Book’s warnings, but in the time before and after her migration, many other Black Americans did. By 1938, The Green Book had reworked how it described the places along the highways that Black Americans might be safest. The book expanded beyond New York City. There were listings for Alabama, Connecticut, Georgia, Illinois, Kentucky, and Louisiana, among others. The font remained green, but instead of advertisements for every restaurant, hotel, and leisure activity (these only appeared occasionally, I assume at a fee), there were rows of listings for each category in each state. Each listing had just a name and an address. With each passing year (save the break Green took in World War II) The Green Book grew glossier and more detailed. The covers, once just plain green writing, now featured black and white drawings of Black American passengers, or photographs of trains and crowded expressways. As Black Americans continued to flee the South (nearly half of the southern Black population) and spread out across the north, The Green Book spread with them, adding more cities each year.

Like that time I took a road trip with my father, my cousin, and his wife. On the drive back to Chicago, state troopers pulled us over. Tinted windows.

Like that evening my father drove me back to my mother’s house after a weekend visit at his home in Indiana. Minutes away from my mother’s home, at a busy six-lane intersection, two police officers pulled my father over under stars and moonlight. I sat in the last row of the van peering out of the window as cars zipped by. When they were halted by a red light, some Black people in the vehicles next to us looked on knowingly. Some appeared visibly annoyed — this police stop was blocking a lane.

“Why am I being pulled over?” my father asked.

“A black man in a big white van kidnapped a little girl about ten or eleven in this area. Can we see your license and registration?”

My father said, “Sure, man,” and reached for the items in his sun visor. I was alarmed. His voice was not its usual lispy high pitch.

The more vocal officer, a white man, shined a flashlight into the driver’s side window of my father’s white Astro van. My father did not complain about the light.

“You got a little girl back there?” he asked.

“That’s my daughter, man,” his voice was lower, trembling at the edges.

The officer ignored him. “You OK, sweetie?”

“Say something, Tiffany!” my father demanded before I could speak a word. He seemed more afraid, more desperate than angry. Horror. Outside. Inside.

“I’m OK.”

The officer shined the flashlight on his license before handing it to his partner to run in the police cruiser.

We sat in silence — a new thing for my father. I watched the remaining officer watch us. My father gripped the steering wheel and looked straight ahead.

After retrieving my father’s license from his partner, the officer said, “Everything looks good. Sorry about this, man. Have a good night.”

In the introduction to the 1949 edition of The Green Book, Green writes, “There will be a day sometime in the near future when this guide will not have to be published. That is when we as a race will have equal opportunities and privileges in the United States. It will be a great day for us to suspend this publication, for then we can go wherever we please, and without embarrassment.” Two years after the Civil Rights Act passed in 1964, The Green Book was published for the last time. There are still just as many reasons for me to drive as there are for me not to.

I am twenty-eight and I cannot drive.

Before moving their vehicles, every driver I have ever known carefully selects music for their journey.

Like in How Stella Got Her Groove Back, when Vanessa, Stella’s sister, cannot drive the ambulance she operates until hip-hop bass booms through the speakers and she can bounce as she rides.

Like Cleo stealing a car in Set It Off and tossing every CD in the stolen vehicle onto the parking garage floor before hearing, “I ain’t no joke, I used to let the mic smoke” over the speakers. I still do this, carefully adding songs to playlists to soundtrack my own movement. I still enjoy the momentary freedom of not driving the vehicle transporting me through time and space, the freedom of being enveloped in the music wrapped around my ears as if I were being tugged along a bumpy road.

When I walk, the horns blare and the drums boom to the rhythm of my steps. When I hear a proclamation like, “N—a, I get my by any means on whenever there’s a drought. Get your umbrellas out because that’s when I brainstorm,” I trust that my legs will carry me anywhere.

Like when Fiona Apple sang, “I still only travel by foot and by foot, it’s a slow climb. But I’m good at being uncomfortable so I can’t stop changing all the time,” softly over upright bass. By foot, I have trekked around La Bastille dipping fries in McDo’s curry sauce, stuffing chocolate and pear pastries in my mouth. I climbed the stairs of Place Du Trocadero to watch the Eiffel Tower shimmer as I rapped, “Got my n—-s in Paris and we going gorillas!” My legs carried me across an ocean to Brighton’s seashore. They’ve carried me to the edge of Brooklyn and back to my grandmother’s house in West Pullman. On the sidewalk outside of my father’s neon, they walked a reluctant mind and teary eyes into Roosevelt University after on a phone call where my mother said, “Your niece missed a field trip to the zoo to see you walk.” They held up my body as it waited in line between smiling graduates in caps and gowns. In those few moments on the main stage under an umbrella of countless warm lights, seizing the opportunity that was the paper symbol of my education did not inch me closer to the kind of latitude white people enjoy. If we are working twice as hard to achieve what they have, we will mimic their history of harm as well as their successes. That is not freedom. I walked across that stage not to be closer to their achievements, but to take a lap for both my grandmother and the legacy past and present that brought us there.

There is no guarantee of safety for a body like mine no matter the place or movement apparatus. I cannot seize and create opportunities that do not bring me joy to preempt the harms I may endure. Each one of us gets to our degree of freedom differently. My brogues tapping the hardwood as I walked off the stage alone, I looked out at my grandmother — the woman that gifted me the power of doing things on my own terms — and felt the freest I’ve ever felt in my life.

Like when 2Pac rapped, “Can you see me now? Move to the side a little bit so you can get a clear picture. Can you see it?”

This is me rollin’.