Practical, antipolitical refusal of the metaphysics of class ‘morals’ are a matter of murmuring. To feel fully the aspirations of the people to which you belong would bring about a terrible and beautiful differentiation in murmuring, an harmonic irresolution of and with and in the choir, in anticipation of a shift in flock, where belonging is in flight from belonging in sharing, at rest in an unrest of constant topographical motion. The weapon of theory is a conference of the birds.

— Fred Moten and Stefano Harney, All Incomplete

from "On Border Dweller Love"

Editor’s note: the below are excerpts from an essay Anna published, “On Border Dweller Love,” which give context to the above poems.

One of my first memories is not even a memory really, but instead, the earliest notion of scale I felt against my body. I near-remember and sometimes dream of standing in the morning shadow of this large looming thing, where even my hand in my mother’s feels cold. Here, for the first of countless times, I measure myself against the height and process of the U.S., Mexico border’s Port of Entry; the armed line separating Ambos Nogales, intersected by the Union Pacific railroad; the oldest rail crossing of any border port entry along the U.S/Mexico border, known for killing workers and migrants traversing its scheduled path.

Standing alongside people, old and young, lined up to be processed and inspected, with the smell of diesel fuel and winter in the air, I inherit a skilled nervousness about how to hold my bladder least suspiciously or how to stifle a wave of anger at the border cop’s roughness with my mother’s belongings. On this morning, I learn that there are at least two types of people in this world: those who ask questions and those who are forced to answer them.

///

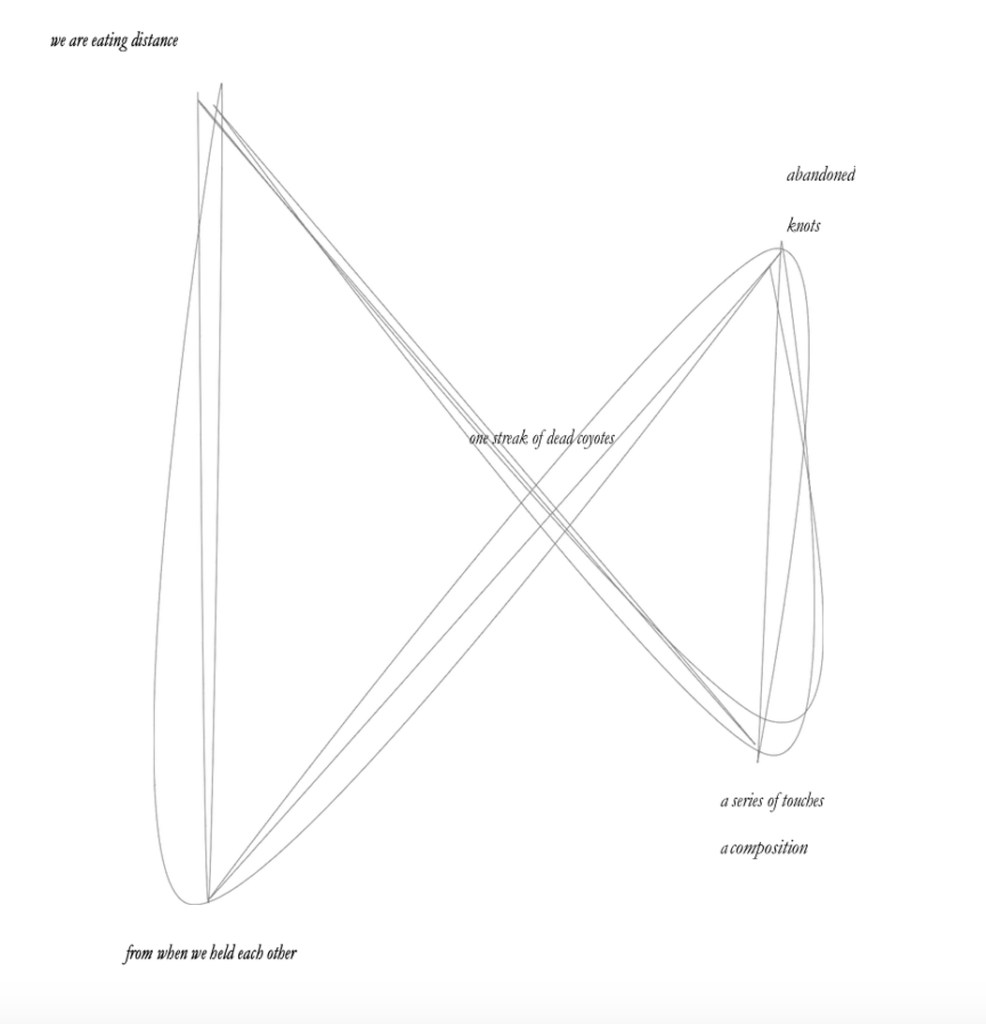

In the kin-based site of the mixed-status family, we develop forlorn care methods for each other. Policies trap us into status categories, creating cracks where presence should be. And so, we let home rot. We un-gather into a constellation of our individual migrations, stuck at separate points on the way to one another, interrupted by criminal records and legal fees. Our bodies trace the shape of a city beneath two countries, an old city where the river runs with a neverending song; a song across different altitudes, many wars, and varied enforcements. Every wrinkle on my elder’s face is a chord in a melody of endurance against the laws and structures that steal us from each other.

///

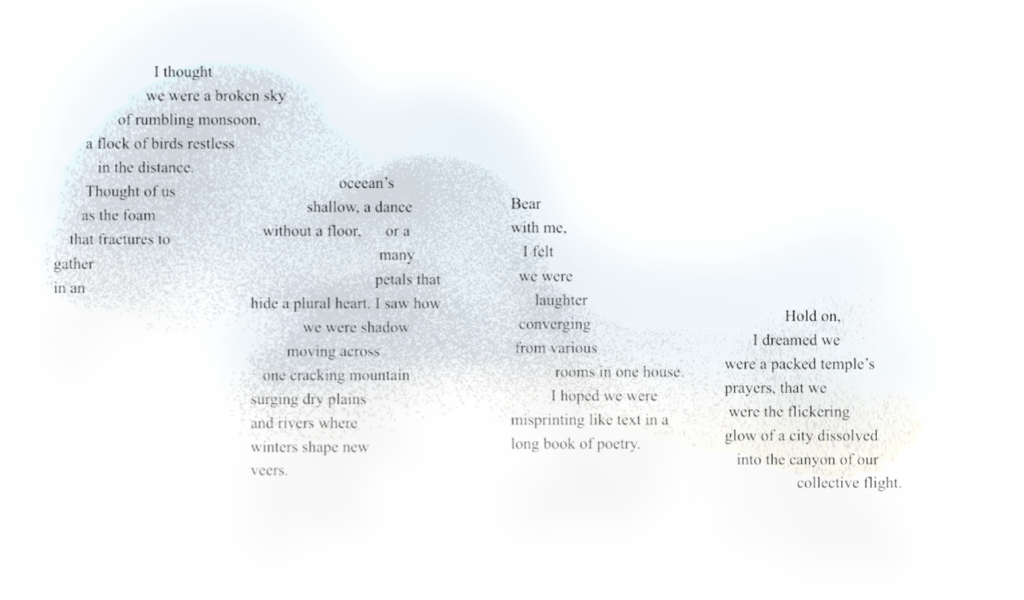

On the page, I unravel sentences into ledges from where I peer into the regional, ancestral practice of naming, questioning, and wondering what a border is made of. Is a border made of steel and sheet metal? Is it made of iron, made of fear? Arrogance? Cheap labor? Is it made first on paper with ink? In a court? In a hateful heart?

It is the Fall of 2024, and on my television screen, the U.S. presidential candidates promise to plan the most appropriate consequences for, “hordes at the border.”

“Horde” is a word from Turkish Urdu, the official language of Pakistan; derived from the phrase: zaban-i-urdu which means “language of the camp.” This word’s phonemic relative (with apparently no shared linguistic roots) is “hoard” from the Old English which is defined as, “a treasure, valuable stock or store, an accumulation of something for preservation or future use.”

At this border, there exists a constant, glimmering mass of people—a prophecy of wandering and returning, ancient to these lands and this desert. The border itself is a wound-born infection, a sickness like a blueprint poison that manifests as legislation and policy, budgets for guns and drones and firearms, fees, uniforms, interrogations, letters from jail, calls from detention centers, searches for bodies, and for the families of the unnamed dead. It is a brutal yet always failing attempt to stifle a mobility that can never be fully controlled. As people gather like antibodies at the site of the lesion, I ask myself: can a wound be the force that drives our resistance? Can the poison be part of our medicine? Can a weapon be corroded to death by its targets?

///

Volatile attitudes and violent policies impacting immigrants, refugees, and Indigenous People make the border a site of continuous loss, however; in this loss, we find a truth about the ultimately failing efforts of colonialism. Our sense of defeat against the court’s legal processes clarifies us. From this clarity, the border-dwelling family occupies ways of relating that subvert the enclosures of legislation and distance.

We love against all odds. We love through dreams, prayers, and offerings. We love through ancestral wandering and sacred commutes. We love through resource sharing and lapses of void in conversation. We know love as a portal, as a way to become and become over again, evading the tracking eyes of many forms of surveillance and category.

Close