The summer before I published my first — and so far, only — book, my husband Alonso and I finally saved enough money and time to spend a week in Paris. It was 2018, and we were celebrating our seventh wedding anniversary, which felt significant. I had not returned since the summer before graduate school, just weeks before I met Alonso. A turning point, decades ago. And as we dreamed of our future, Alonso and I imagined traveling to Paris together someday. With another turning point ahead (my book), it was time. I enticed him with descriptions of the delicious yogurt, pastries, and hot chocolate that did not taste the same anywhere else in the world and the best places to view the city at different angles and times of day. Not that he needed much convincing. Alonso had always been interested in France, especially Paris, as it was a mythical place in his imagination — a historically renowned refuge for African American artists and writers. Together, we said aloud the names of the Harlem Renaissance writers we had read: Zora Neale Hurston. Langston Hughes. Nella Larsen, Richard Wright, Dorothy West. Over many years, whenever we fantasized about traveling to Paris, my husband would wonder aloud if this could be true: Was there a place in this world where the weight of white supremacy felt lighter?

Alonso and I grew up in different worlds. Me in New England, an immigrant from the Philippines. He in the South, a Black American. And yet, we are so alike; we were both raised Catholic within a close-knit multigenerational family. We’ve both experienced racism, then and now — but it was not until later in life that I realized how much our perceived identities shaped these experiences. So much of me wanted to believe we were the same and that any of our differences could be understood through the sheer force of love.

Growing up, we both spent our free time reading in the public library, and this love of books brought our lives together one sunny afternoon on a college campus in Southern California. We were the first to arrive at a reception for graduate students of color on full fellowships, our funding meant to encourage diversity in the academy. We were both far from home and in our early twenties, our cheeks flushed in the late summer heat. We shook with the nervous energy of two people who believed that their real lives were about to begin. I was drawn in by Alonso’s Southern accent and physical presence, attracted to his warmth and kindness.

By spring, we were dating and in love, glorious love. Together, a beautiful future seemed inevitable. We were grandiose, believing that the very existence of our interracial relationship imbued us with the power to remake the world. And wonderful, magical things did seem to happen around us. The first time that we attended the Los Angeles Times Festival of Books, two women in their eighties sitting in front of us turned around to stare. They smiled approvingly as they studied us up and down, and we beamed right back at them as if to agree with their assessment: Ah, yes — here is a mixed couple whose very existence is living proof of the bright future of America! They introduced themselves as Grace Paley and Tillie Olsen, whose work I had just taught from an anthology. I felt as though they were blessing us.

Soon, Alonso and I were living together in Long Beach and on our daily commute to school, we would listen to 92.3 The Beat, a Los Angeles hip hop radio station with the slogan “no color lines.” Alonso would drive, stopping and starting in traffic, and I would nap in the bucket seat next to him, my hand resting on his leg. No lines between us.

Together now for half of our lives as husband and wife, we are so intertwined that I sometimes forget that we are not exactly the same. People are generally happy to see me, especially if I am smiling, which I have learned to do a lot and very pleasantly as a kind of grease for the wheels of my life. The worst things that have happened to me in interpersonal encounters are the occasional, insulting ideas about Asian women’s subservience or the shortsighted assumption that my English is very good for an Oriental. Conversely, besides the sociological consequences of structural racism, almost every aspect of Alonso’s life is haunted by anti-Blackness. Since he has encountered white people, their racist insults have wormed their way into his ears and shaped his thoughts, and from the time he entered school, his body had begun to absorb the countless slaps, punches, and kicks of white supremacy. Shortly after we moved to Boston, he was attacked by a group of young men while he walked to an evening meeting. They kicked him so furiously that his head swelled, misshapen and monstrous. At the hospital, I did not recognize the man I slept beside every night. If you’re wondering if this was just a random act of violence — wrong place; wrong time — while they beat him, his assailants also used that word, the one that I’m told is an important word that new immigrants to America learn, along with racist jokes, so that they can know what they shouldn’t be. When I encountered my husband’s bloody and bruised body against the white hospital sheets, I thought, Here is the word made flesh. I was devastated to learn not long after that my husband’s projected life expectancy is a good ten years shorter than mine.

On occasion, our class differences come up, too. My parents and their immigrant friends were physicians, or they owned small insurance or real estate businesses, while Alonso’s single mother worked shifts at a phone company after graduating high school. When Alonso first told me that his grandfather was a painter, I gushed, “What did he paint?” I imagined thick oils on framed canvases. Alonso answered, “Houses,” and still, I didn’t understand. I was curious about why his grandfather’s subject as a painter was houses. Alonso corrected me, “Sometimes the inside walls; mostly the outside.”

It wouldn’t be the last time I’d make the mistake of assuming that Alonso experienced the world the way I do. After all, I grew up on a steady diet of aphorisms assuring me that the color of one’s skin didn’t matter. No color lines. Love conquers all. As a child, white people would tell me how they didn’t see color. I could be purple or blue and they would still accept me. And yet, despite all the love supposedly abounding in the world, racism is still a formidable conqueror. I should know better. I’ve experienced bigotry and the effects of systemic racism firsthand as an Asian American immigrant woman. But even from my view in the passenger seat of my husband’s life, I cannot fully appreciate and comprehend the extent to which his life has been determined by anti-Black racism. We talk about race almost every day of our lives together. Not by choice, but by necessity.

Alonso once told me that when he was a boy, before he left the house to play with friends, his grandmother would ask if he had a dime, later upgraded to a dollar, in his pocket. Granny told him that this was to “keep the ‘haints’ off you.” When I asked him what a “haint” was, Alonso explained to me, his Asian American wife, that “haints” are part of Black American folklore, a version of “haunt” in African American Vernacular English used to describe a ghost or a spirit. But as he understood it growing up in the South, they used “haint” to specifically reference being haunted by the police. If you didn’t have any money on you, you could be picked up by the police for loitering, an easy crime to be guilty of. And before he stepped out the door, Alonso’s mother could not stop herself from telling him for the umpteenth time that he couldn’t act out in public the way his little friends did. He could not get away with things the way white boys could. “You’re not white,” she would remind him. As if he could ever forget.

Alonso’s ideas about France began back when he was just a boy growing up in Louisville, Kentucky. He and his family lived in Smoketown, in an area of the city that was built by his ancestors after they came out of slavery. Discussions about the impact of racism and white people went on every day; they could not escape it.

After school, while his mother worked her shift at the phone company, Alonso’s grandfather watched him and his twin brother in the afternoons. They played on a patch of grass behind the brick house that the St. Peter Claver church owned, where his grandparents were allowed to reside in exchange for work. Later, we learned that the Catholic church put up St. Peter Claver churches in African American neighborhoods in particular, as he was the patron saint of enslaved people. My husband lived in this same brick house after his mother left his father, alongside his two uncles, who went to work digging ditches and working the factory line right after they earned high school diplomas. The family lore is that his uncles had been offered the chance to go to college, but didn’t pursue it.

By the time Alonso was in middle school, his grandfather knew that he was dying of cancer, but he still had enough energy in the afternoons to pull a discarded mattress from the shed and hold court from a prone position in the center of the floor. He told stories about his life, which made my husband want to see the world — including Paris. Despite the horrors he experienced in World War II, his grandfather had wonderful memories of being in France and serving in the US Army, which brought him outside the prison walls of the Jim Crow South for the first — and last — time in his life. After his military service, his grandfather would never leave the US again. I don’t think he even left Louisville.

In one of his stories, Alonso’s grandfather recounted how one day in the mountains of France, at a pitstop, he’d heard his name being called out — “Bill Wright!” — in a cadence that only someone from back home could affect. Standing there, an ocean away from Smoketown, was his cousin: an apparition, a reminder of his past life, and undeniable proof that wonderful, magical moments happened in this world.

French women were very beautiful, his grandfather made sure to mention on more than one occasion. And the villagers were polite, even when they were nicely asking to see his tail. His grandfather had initially been confused by the request. Why did the French villagers believe that he had a tail? He soon learned that the white GIs encouraged the white villagers, who had never encountered Black Americans before, to ask the Black troops to pull down their trousers so that they could prove that they were part monkey. What a funny prank.

If curiosity about Paris as a respite for African Americans was the reason my husband wanted to travel there, I wanted to return to that city because it was there, many years ago, that I had first conjured him, describing him in my notebook even though we hadn’t met yet. A few months before we found each other, I had quit my job and moved to Paris for the summer. Funded by scant savings and multiple credit cards, I spent many afternoons in cafés drinking café au lait and smoking Gauloises while I filled French notebooks with my writing. In a small gray notebook, I made a list of what I wanted in the man I would someday marry. Even then, I sensed I was describing an impossibility; and yet, two months later, Alonso appeared in front of me, moving in and out of a yellow beam of sunlight that was getting in his eyes.

Back then, I was young and naïve enough to believe that being in Paris would help me become a writer. I also believed that spending time there would change me into someone worthy of love. I’m not sure where I learned these ideas, but I planned to return from Paris a better woman having breathed the Continental air, having spoken French, having looked at art and architecture, having absorbed Culture. When I would walk past tourists in line at the Louvre and the Eiffel Tower, I believed they were wasting their time. I was seeing the real Paris as I fetched my baguette from the market or wandered to some out-of-the-way neighborhood or garden. I spent many leisurely hours at Shakespeare & Company bookstore where I met the owner, George Whitman, and attended his literary gatherings, drinking lemonade in the company of cats and fellow wannabe writers.

I imagined that I was creating a superior version of myself. All I needed to do to become a real writer was stand in front of famous paintings at the Louvre, sit at the cafes where Hemingway did, and walk along the Seine. At least, that’s what I believed at the time, even though I did not even speak enough French to do anything more than simple customer service transactions. Decades later, I would realize this was a ridiculous notion. I could never spend enough time or money in Paris to become white.

To prepare for our trip to Paris in 2018, Alonso learned enough French to order deux café au lait and deux croissants sil vois plait, the only French we really needed. While he doesn’t speak French, he picks up languages easily. He is fluent — speaking, reading, and writing — in Spanish and Portuguese. His graduate study in linguistics and these two languages, he says, makes it easy for him to comprehend spoken French. We had heard that sometimes Parisians could come across as rude to tourists, even if one tried to speak French, but we thought — innocently, or perhaps ignorantly — what kind of person wouldn’t appreciate a visitor attempting to speak their language?

Despite our best attempts to be good travelers, however, our first days in Paris did not live up to the romantic idea in our heads. And how could it, after a lifetime of imagining oneself into postcards and paintings beside the Eiffel Tower, the Arc de Triomphe, and Notre-Dame? There was more traffic and more crowds than we had anticipated. And we witnessed more than our fair share of moments when resentments and inequities bubbled into actions, like when our taxi driver raged against a fellow taxi driver until he punched out his side mirror. We watched a man grab a tourist’s bag and run through the square, as if in a relay race, to hand it off to another man who disappeared almost instantly.

And there was also the fact that by the time we set foot in Paris, we were fully middle-aged with most of the romantic notions of youth long-dissipated. For his work as a photographer, Alonso had traveled extensively throughout Africa, Asia, Europe, Latin America, and almost all of the United States, observing societal differences in every place — but he still held out hope that the Paris we visited in 2018 might still be the Paris of the Jazz Age. He was disappointed to see such rampant segregation, inequality, labor stratification, and people who looked like him in the lower end of the economic hierarchy. He tried to be a good tourist and keep from asking the tour guides, “Where did this wealth come from? On whose backs?”

Midway through our trip to Paris, we booked an excursion to Monet’s garden in Giverny. Blocks away from the Eiffel Tower, and with just minutes to spare before we needed to get on our tour bus, Alonso and I stopped to grab a bag lunch at a nearby café. There were cute baguette sandwiches with pâté or ham and butter, apple cakes, and croissants in the glass display case. Everything looked good and we were hungry. We stood at the register and waited patiently as waiters walked past us; it wasn’t clear who would serve us. A woman wearing a white apron, someone I assumed was a bartender, stood behind a brass beer tap and cleaned glasses with a white cloth. We stood there for long minutes and thought of leaving, but we had already invested too much time at this place to start the process all over again at another café.

I watched the woman by the tap wipe the inside of another glass with a white cloth and then turn it over. She took another glass and then pulled on the tap. I watched her drink the beer in one gulp and then dry her hands on her apron. I pleaded at her with my eyes, and Alonso might have waved to her then, in a friendly way, not in a way that demanded her attention. Finally, in French, she asked us what we wanted. My husband spoke first, pointing at what he wanted. He held up two fingers. “Deux.” The woman and my husband went back and forth a bit and seemed to have concluded their interaction, so I asked, after a small beat of silence, to add a slice of apple cake to our order. I didn’t notice anything amiss, but perhaps I’d been too focused on catching the bus, imagining myself into the next place and not being present. Alonso held out our euros to pay. The woman stood in front of me and waved her hands. She raised her voice, speaking enough English to say, “He is slow. He is stupid. I don’t talk to him anymore. I talk to you.” I couldn’t see Alonso, but as I counted out the money, I felt his presence behind me, shrinking.

My body understood the blow before my mind did. The hair on my arms prickled and I suddenly wanted to cry. I didn’t understand what was happening, but we were already so far into the play that I continued with the improvisation, yes and, until we finished the scene. The bus was leaving in mere minutes. I paid for the items and accepted the change, averting my gaze from both the woman and my husband. Even though I couldn’t name it until later, something traumatic had just occurred, and my initial response to freeze in the face of overwhelm was instant and familiar, an old trauma response many years in the making. I am a person with one eye on the exit routes of any room I’m in, and all I wanted to do in that moment was to escape. I felt ashamed, but I desperately wanted to escape it. We grabbed the bag of food and walked away silently.

Blocks away from the café, my husband finally spoke. “That was racism,” he said. He had been feeling uneasy since we’d first arrived in Paris, but wasn’t sure why until that woman called him “stupid” and “slow.” Finally, his observations and complaints over the past few days had begun to make sense. Despite France’s policies against collecting data on race and ethnicity and their insistence on a colorblind society, even here, my husband was haunted by the specter of racism.

I stopped walking. Finally in the fresh air, I could think again. “Let’s go back and complain to the manager,” I said. I wanted him to know that I supported him. That I would stop everything to show him that. So what if we forfeited our paid excursion that day?

“And what will that do?” he countered. “We’re going to miss our bus.”

When I thought back to our various interactions with Parisians at restaurants, museums, and shops earlier that week, I realized that even though Alonso had taken the time to learn some French, I would always take over to pay for and conclude the transaction. I’d thought I was jumping in to make things faster and simpler, because I often had my wallet ready. I had not given this impulse a second thought, nor had I ever entertained the notion that some people might not want to talk to him because of how they read him as an African immigrant or Algerian or some other Brown person they despised. Needless to say, our day was ruined, and frankly, the rest of our long-awaited trip to Paris had also soured. My fantasy of returning to the place where I had dreamed my husband up and fantasized about us strolling along the Seine at sunset, hand-in-hand, quickly evaporated.

Next to me, Alonso seethed in silence the entire bus ride to Giverny. In my mind, I went over what happened, “perseverating” as my husband sometimes complains, but I couldn’t find a way to change the story, to explain it any other way than what it was: a customer service experience of interpersonal racism that was so direct and simple that it was confusing. “Your husband is stupid. I am not talking to him anymore,” the woman had said to me, her blue eyes big behind her glasses. Her face scowled as she handed me the white bag of pastries and I’d only thought of the bus we needed to catch and how I wanted to complete the transaction as quickly as possible. But even now, I can remember the sudden electricity in my arms; how I felt a hundred needles as thin as hairs prick my skin; how my body screamed for me to act. Why hadn’t we left the bakery as soon as we realized what was going on? Surely a few hours of physical discomfort, low blood sugar, and churning stomach acid was worth enduring in order to show this woman that we refused to swallow her racism.

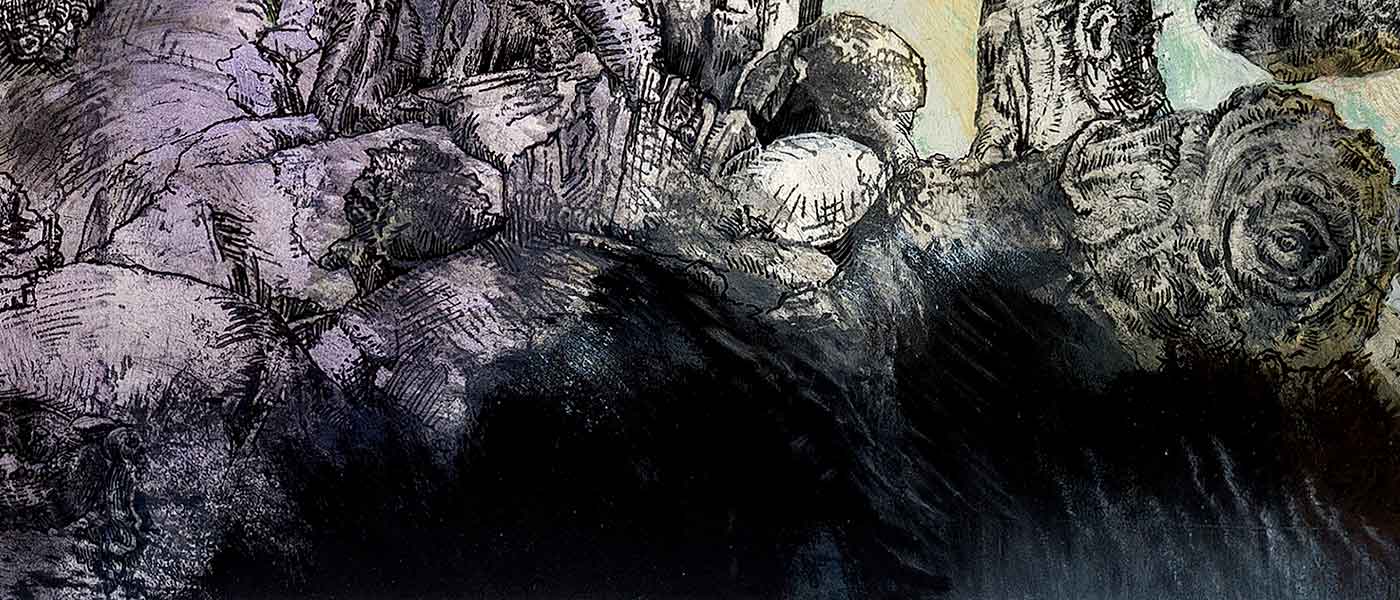

We tumbled from the cold, air-conditioned bus into the sweltering summer afternoon. Alonso shook his head and I read his face. “Whose idea was this?” he asked. He surveyed the throng of tourists who wanted to walk the same pathways as us and take pictures on the same Japanese bridge. Did he mean our decision to buy tickets for this excursion, or the fact of the site itself, a place for tourists — white tourists — to imagine themselves into Monet’s paintings?

I shrugged, annoyed and impatient. Why couldn’t he appreciate this? “It’s Monet’s garden,” I said. “Like the actual garden from the paintings.” (One might never see an actual Monet painting, but you could not escape the countless reproductions on calendars and college dorm posters, stationary sets and mouse pads, kitchen dish towels and playing cards. We didn’t own any of these things, but I remember seeing a Monet postcard framed and hanging on the bathroom wall at his mother’s house in Louisville.)

Alonso closed his eyes for a moment and then nodded. He was going to endure this quietly, for my sake. I left him alone at the back of the tour group where he lingered too far behind to hear our guide’s voice narrating a history made for tourists.

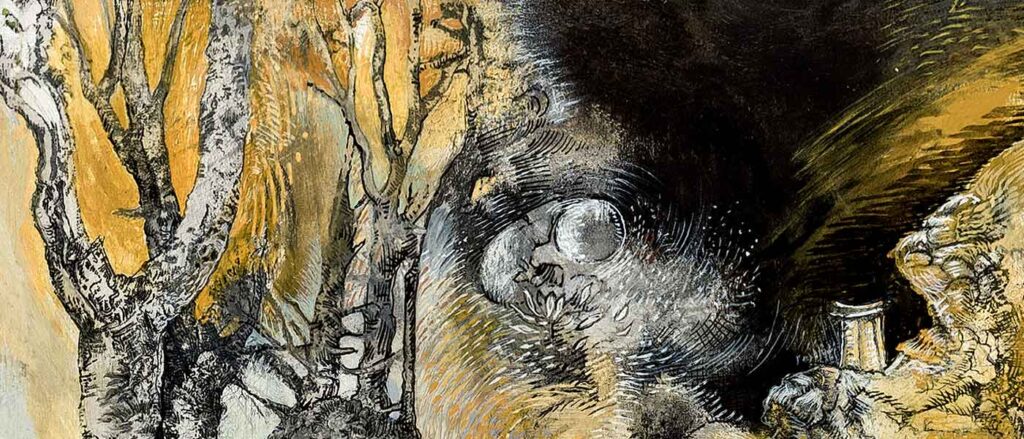

At this point in our vacation, Alonso was done with looking at old paintings by white people, which inevitably focused with a narrow lens on what the artists deemed worthy of attention — their gardens, their buildings, their animals, their belongings. Sometimes in paintings of wealthy families flaunting their status, there was a dark figure in the background or to the side of the subjects: the enslaved adult or child who worked for them. Alonso always pointed that person out and searched for their names to no avail. “That’s who I want to know about,” he said. “What’s their story?”

Just a few days before we ate our racist pastries, Alonso had this same reaction in the Louvre. Once we were inside the museum, we realized that we had made a terrible miscalculation by visiting during the height of tourist season. The hallways were as crowded as a subway station during rush hour in Manhattan. Still, it was a thrill to stand before the actual paintings and sculptures of works that I had only seen in art history and Western civilization textbooks. I felt as if I’d been dropped into an after-party at the Oscars, walking past movie stars of films I had forgotten I loved. “You’re here,” I’d say, sometimes aloud, always in awe; “My God, it’s really you.”

We stopped in front of Théodore Géricault’s The Raft of Medusa, swaying like seagrass as the current of museum-goers flowed around us. We could not look away from the scene of hell: the aftermath of a shipwreck, the dead and the about-to-die. Alonso pointed out the man with his back to us, the one drawn with brown pigment. He waves a red and white cloth, the highest point of the triangle above the writhing bodies on the raft. He alone sees what the others can’t: Soon, they will be rescued. Later, the survivors will tell a version of what happened, inevitably a story that erases Black and Brown people from the narrative. A story like all the stories I grew up on in which white people are the only heroes. When I first met Alonso’s mother, she was excited to ask if I knew that a Black person had invented the traffic signal (Garrett Morgan) and performed the first successful heart surgery (Daniel Hale Williams). If it wasn’t for Black people, she told me, we wouldn’t enjoy important innovations of modern life such as home security systems, cataract surgery, blood banks, and even the super-soaker toy. I listened, rapt. “No, I did not know.”

Before long, we found ourselves holding our breath in the room that everyone wanted to enter — she was here. People crowded in front of the Mona Lisa, pushing and posing for selfies, another sort of conspicuous consumption. We turned our backs to her famous smirk and moved toward the painting on the opposite side of the room, Veronese’s The Wedding Feast at Cana. Within seconds, Alonso pointed to a figure. “There he is,” he said. “The slave.” The rest of the day at the Louvre, I joined in his game, both of us finding the dark figure in other works. At first, this made me feel a little sad, to see the art first for its demonstration of racial inequality, but on another level, I was relieved because we were doing something together by naming the unnamed. Acknowledging the ghost took power away from its haunting.

Naturally, I was disappointed that Alonso was having such a terrible time. I was constantly aware of all the moments in which I tried to spare my feelings from him, and in which he did his best to appear as if he were enjoying himself. I worried about what this meant about our relationship and our ability to be close when we experienced the world so differently. Despite the enormity of our love, I was scared that it would not be enough to bridge this difference. So each night when we would return to our hotel room after touring Paris’s museums and sites, I’d insist that he tell me whatever was bothering him. I listened as he told me that as a Black American, he did not enjoy being surrounded by iconographies of slavery and colonialism; that whenever our tour bus drove past the Luxor Obelisk in the Place de la Concorde or we stopped to admire art and architectural references to Africa, Asia, or the Middle East, he didn’t think about the craftsmanship and artistry of the monument. Instead, he imagined the suffering that made those things possible. The military conquests and the looting. The extraction of labor and resources. After several days of meals, my husband admitted how much it weighed on him that everything we’d put in our mouths had a painful history. Pho, falafel, café au lait, even sugar. He said, “We are eating imperialism. Every person of color we encounter — the Algerians, Vietnamese and other Southeast Asians, and the Africans — tells the story of French colonialism through their presence. They are here because the empire was there.”

On some level, I agreed, but eventually, I grew impatient and irritated. I wished, for the sake of our vacation, that he could not see and not know. I could not enjoy Paris, even though dreaming and planning for this trip had gotten me through so many months of working to save up for it. It was the carrot I’d grown all spring and now that it was summer, I was ready to harvest and eat it, only to find it shriveled and rotting. Perhaps that’s what privilege afforded me: willful ignorance to the ugly side of this story. I did not know what it was like to walk around this world in his body, even though I’d worked to pay such close attention during our marriage.

Alonso’s presence as a Black man changes any space he steps into. If he has spent his life being haunted by racist ideas and expectations, he has also simultaneously embodied the apparition. He’s told me how much he notices, even if he pretends not to see. It does not benefit him to openly react to white people’s reactions to him. He sees when they clutch their purse. He sees them crossing the street to avoid him. He sees their faces when an elevator door opens and they are startled and unhappy to find him standing there. He complains that when he stops his car in a busy area in the city, he has to shoo white people away because they pull on his car door handles trying to get in, assuming he’s their rideshare driver. He wants us to get a dog as soon as we’re able because he says that when he’s walking a dog, people smile at him for once. They greet him instead of pretending he’s not there. They’re not so afraid.

And this is just the tip of the iceberg.

Even with my spot in the passenger seat of anti-Black racism, there is a distance that I can’t bridge. I can shake my head and tell him, I’m sorry, and, What do you need? But this is practically nothing against the constant and mundane humiliations. The dangers of his very existence.

Several years after our trip to Paris, back home in Boston, my husband was crossing a city street during his evening commute and as he was almost across the last white lines of the crosswalk, a driver lowered his window to shout insults and expletives at him. The driver sped away, leaving my husband startled and furious. Alonso went through the checklist in his mind of what he could have done to inspire such a reaction. He had crossed a public street at the appropriate time in the appropriate place. “The man is yelling at me behind the wheel of a two-ton weapon about what a piece of shit I am,” my husband told me later that evening. “And I have nothing, no protection.” In moments like these, there’s only one way to respond: he quickly stepped onto the sidewalk and into the building where his meeting was about to start. His life in public spaces is, and always has been, an exercise in restraint, which removes him from the immediacy of a potentially deadly situation, but not without injury. When he returned to me that evening, he was carrying the rage that the driver dumped onto him, and dropped it like a heavy bag onto the bamboo floors of our home. He recounted what happened as I desperately tried to think of solutions. There were none.

When I show Alonso what I’ve written about his experience later on, repeating back my notes from when I interviewed him and reading aloud what I thought I’d heard him say, he shakes his head no. Another communication gap, this distance between fantasy and reality, between romance and a long marriage, that seems impossible to close. “In Boston, there’s a particular kind of hostility and aggression that I experience in public spaces that you and other people just don’t get. I didn’t feel this when we lived in LA. It’s more complicated for me than for you to just go about my business. Sometimes it’s easier for me to just stay home,” my husband tells me. I prick with the memory of how disappointed and sometimes even despairing I feel when he declines my invitations to events and dinners. These days, I rarely bother asking.

But it’s difficult to admit how right he is; a few days after that incident in the street, while my husband was at work, I took over hosting duties for our visitor from Australia, my husband’s cousin, who is perceived as white. We spent an October day together in Salem, Massachusetts, which was surprisingly crowded with costumed tourists on a weekday. As we read the gravestones of those accused of and executed for witchcraft, I thought about how over 300 years ago, these people were killed because of a story about who they were. And at the same time, I noticed how relaxed I was. With this “white” man by my side, I wasn’t worried that a moment with the wrong person could turn the day ugly in a second. I watched how strangers gave my husband’s fair-skinned cousin grace again and again, how easily and unguarded he walked in public space. He and my husband are blood relatives, but their lives are substantively, heartbreakingly different. He enjoyed a freedom Alonso could never have.

Some years before our trip to Paris, I hosted a friend for a few days while he was in town to promote his first book. He was tall, handsome, and white, but not so much of any of those that I thought he stood out in any particular way. He wasn’t a peacock. Alonso was out of town, and as I drove my friend around the city and accompanied him to bookstores, restaurants, and bars, I was astonished over and over again when people seemed happy to see us. Men and women at front desks, no matter their age, smiled at him and welcomed us — “no problem, come on in” — even in crowded restaurants that I wouldn’t have dared enter on a weekend night without a reservation. Later, when I realized my friend had brought loose weed with him (which was illegal at the time) on an airplane over state lines, I asked, “Weren’t you afraid of getting caught?”

He shrugged and said, “Nah. And even if I did, I’m white. What’s the worst that could happen to me?”

Upon hearing my friend’s nonchalant admission, I suddenly felt thrust into a sideways reality. It’s the way that I imagine the main character in Eddie Murphy’s 1984 Saturday Night Live mockumentary, “White Like Me,” experienced Manhattan as an undercover white man in a three-piece navy suit and peach-hued pancake makeup. As he began interacting with the world as a white man, he was baffled by the new and strangely pleasant interactions he would suddenly have with sales clerks and bank loan officers. Later on in the film, on a city bus after the only other Black person disembarked, the passengers smiled at each other and some stood up to dance. The mood was celebratory and triumphant, but what exactly were these bus passengers, who were perfect strangers despite their performed comfort and familiarity, actually celebrating? It was the moment when the last Black man exited the bus. This is what I imagine my husband experiences in public spaces. People are happy when he’s gone.

Near the end of our long-awaited Paris trip, I looked up from my phone as I rested on our hotel room bed. I learned from my newsfeed that just one day before our visit to the Louvre, Beyoncé and Jay-Z had apparently dropped their video, “Apes**t,” which was filmed throughout the very same museum, and likely explained the crowds. “Does it mean something to you that Beyoncé and Jay-Z took over the museum and made this video?” I asked Alonso. I kept babbling on anxiously, excitedly. I wanted to feel close again, sharing intimacies. “Has anyone else in music done something like this? I mean, it’s the Louvre. And they placed themselves next to these icons of Western art.”

But my husband must have been tired and not up for a conversation about pop culture. He reacted in a way that I’ve come to recognize after many years of being together: it’s meant to keep the peace. It works sometimes, to pretend things are better than they actually are. But it didn’t escape my notice then how our decades-long conversation about the role of racism in our lives had recently seemed to arc downward more and more, toward despair. He rubbed his lower back.

“What’s the matter?” I asked. “Are you in pain?”

It was true that our hotel bed was not as comfortable as our bed back home was, and it was also true that we had been walking a lot. I don’t think he noticed, but as he reassured me, he patted his pocket as if to feel for a dime or a dollar, before moving his hand to where his back ached, touching the exact place on his body where villagers expected his tail to be.

I don’t want to tell you this part of the story, but because we have come this far together, I will. I was walking home on an August night some weeks after our trip to Paris. It was close to 10 p.m. after teaching my summer class. Because the campus was empty and dark, I had called my husband and asked him to keep me company while I walked toward home. But as I neared our apartment building, I spotted suspicious movement up ahead and said, “Hold on, I see someone moving behind the dumpsters. It’s a man.” My heart began to race and my breathing quickened, an anxiety response. The man wasn’t white, I noticed, but did that matter? Wasn’t I just reacting to seeing a strange man in a place I didn’t expect to see one? Wasn’t I simply exhibiting the proper response to my own past lived traumas, and exhibiting the appropriate amount of fear that a woman alone, in public, late at night, should have? My thoughts began to fire rapidly as I realized the man was standing exactly between me and the entrance to my home: between danger and safety. I knew my husband could hear my breathing through the phone, then, and in a moment of recognition and protectiveness, he said, “Just stay where you are and stand in a streetlight. I’ll find you.”

So I did as I was told, and waited guardedly by the nearest streetlight. I watched the man at the dumpster come directly toward me. I was shaking, but as soon as I recognized my husband’s face in the light, his phone in hand, I smiled at him, blinked back my tears, and mustered a cheerful smile.