What follows are three pieces that offer up three different glimpses into Featured Artist Saffron Douglas’s exploration of queerness as an ever-evolving term, one that many within and outside of the LGBTQ community at times co-opt without fully understanding its complexities.

I. STRAWBERRY KABOB

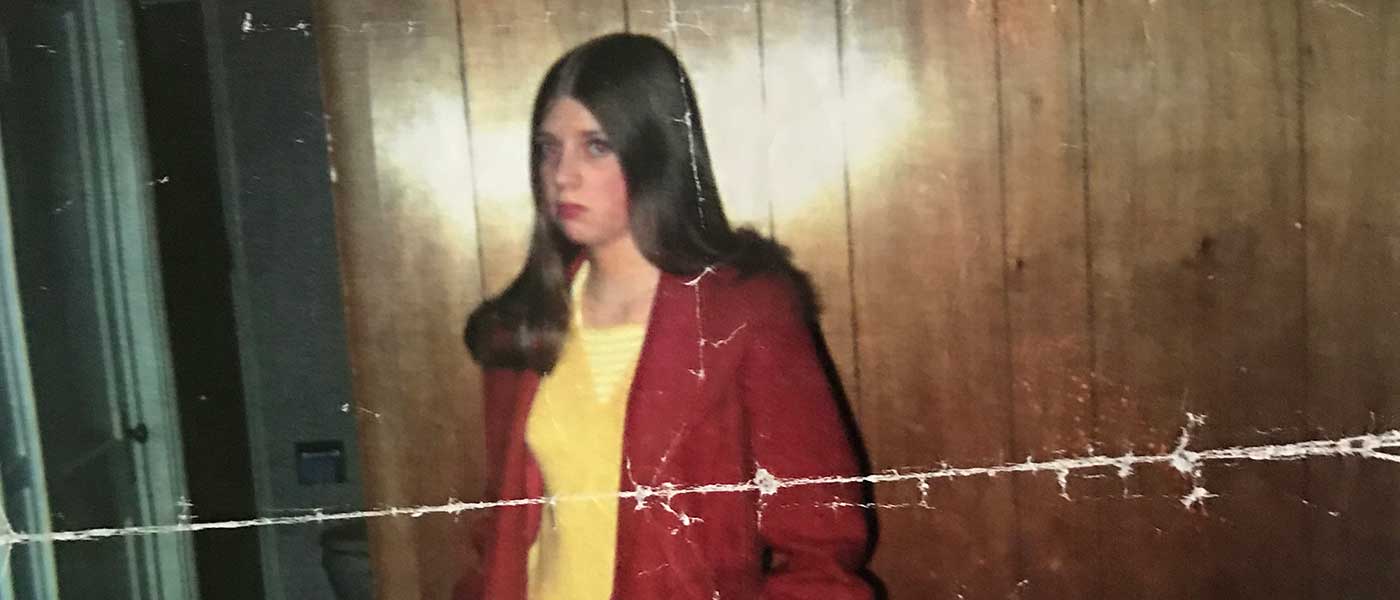

In 2007, I had just freshly graduated from high school. I was a year ahead of my class and had put in the extra work due to acute boredom — one of the few times that apathy led me to do more work rather than less. Academics came easily to me, and while I was my spritely self with my few close friends, I was all but silent with the rest of the students around me, just as they were to me. Through that silence, though, I perceived a palpable tension I created simply by existing, and perhaps it was this more than the apathy that I was trying to escape.

Being visible never felt like a choice I was making. It was a riptide urge surging from somewhere deep within my subconsciousness with an inevitability beyond even the outer edges of my perception. At that young age, I wasn’t self-aware enough to question my compulsion to swish.

That fall I was sixteen, and I started attending Tarrant County Community College. In my too-small thrift store tees and hand-snipped skintight jeans, I stomped a little bolder and a little faster down the hallways than I ever had back in high school. The campus was filled with nice moms who looked out for me in my lab class and younger people whose staring ranged from clearly unabashed to nervous and weakly veiled.

Unlike my experience in high school, this was the first time in my life where I noticed being noticed without the requisite buildup of tension. I even began to intentionally reroute my walks to pass through more populated areas or through buildings I didn’t really need to be in so that I could feel more eyes on me. I made wake, and for this brief sunny moment in time, gained only reward.

Midway through the fall semester, I was fully seventeen, experiencing what most people my age probably started to feel years before in high school: invincibility. I skipped my 8 a.m. English class almost every week (which would become my first failure), I was acing everything else, and I spoke up in my classes — especially in my labs with the nice moms. And in the flow of my first dose of real adult confidence, I began to catch sight of someone else like me.

He wore a bright green track jacket which, at the height of the Abercrombie and American Eagle fashion age, made me melt. His hair was long, black, and straight, and over the span of a week, I noticed him so much that I wondered how I hadn’t seen him before. On any given day, I’d linger in the library to be seen by my fellow library-goers while I idled away with my homework.

On one of these days while I was lingering, Green Jacket came into the library with his moody, downcast eyes draped by straight black hair that looked touchably soft. He was a fast walker, and after rounding the library to grab the book he needed, he stopped by the checkout desk and then started toward the exit. Fortunately, I was about done staring at my unfinished homework, and so I made my way to the same exit, hoping the universe might choreograph an accidental meet-cute between us.

As I happened to be heading to my car at the same time as him, I began to notice the tension building in the space between our bodies as he noticed me behind him. I felt heat prickle under my skin and my heart beat flutter as I suddenly realized I had no idea how to do what I was about to do. We stepped out into the chill, overcast air of the south lot. He not-so-smoothly turned his head in my direction as if to look at something in the distance, but I felt his eyes flick over me more than once, cueing absolutely every single sweat gland in my body to purge. I came to the panicked conclusion that I just wasn’t a first move kind of girl so I let our paths split in the lot as he headed toward his car and I headed toward mine. I crumbled and buzzed in my blue-ish purple Ford Taurus with six cylinders, a CD player, and pink furry dice hanging off the rearview mirror.

Later that same week, I was having an uneventful day: I attended my classes, perform-studied in the library, and took my long walking routes, this time not to be seen, but to try to catch sight of Green Jacket. He wasn’t in any of his usual spots so I headed to my car parked in the same south lot as before. At that age, any small disappointment felt like complete and universal rejection, and so it was with all of the forces of the world against me that I climbed into my Taurus.

As I sat down and stuck my key into the ignition, I happened to look up. I paused. There on my windshield, tucked securely underneath a busted windshield wiper, was the familiar rainbow glimmer of a burned CD in a bright sour-apple green jewel case.

Key still in the ignition, I climbed out the door to grab the case and brought it in. Cracking the case open, I took out a torn bit of paper that had a tracklist on one side with bands like Duran Duran, The National, and what I can only remember as a bunch of white man names I didn’t recognize but would later pretend to adore. On the other side was a short note that said something like, “I’ve seen you around campus, I know it’s creepy that I saw the car you drive but I wanted to talk to you…I think you’re really cute and I think you have noticed me too.” At the bottom of the letter was his name, Brady, and under that, his phone number.

Everything inside of me contracted in disbelief and then exploded outward with the gleeful giddy laughter of my first ever boy number. I happy-danced in my car, stomping my feet on the floorboard while shaking my head and squealing. When I finally gathered myself, I somehow exercised the restraint to not call him immediately and instead headed to work at the Hulen Mall, where I sold watches and pre-hipster clothing at Fossil.

I got off a few minutes early that night and decided to call him as I strolled the mall close to closing time. As inexperienced in the world as I was, I knew better than to be on the phone in a parking lot at night. Then I stopped. In considering my safety, it hit me: What if this wasn’t the cute emo boy I had silently courted around campus? What if it was some older man who had been noticing me without my noticing him? He’d seen the car I drove and presumably had some idea of my routine and schedule. I was scared, but I wanted so badly for it to be Green Jacket, who was just a bit taller than me when he wasn’t slouching. He had to be the one who loved that clumsily curated mix of punk and folk bands I had listened to for the first time on my way to work.

I headed across the second level of the mall to where my friend worked at Godiva. She was a smart girl who felt like she had been born as a well-adjusted thirty year old. Plus, she was a known friend to the only other gay I knew of in our school district. I trusted her and visited her often. Also, around closing time, there would always be at least one giant chocolate strawberry I could get from her. I told her what happened earlier that day in between bites of a banana-strawberry chocolate kabob which, looking back, was an auspicious treat as those were seldom left over at the end of the day. She urged me to call him, assuring me that I was probably safe. “You said he saw you in the parking lot, right? It’s not that weird that he knows you drive a car with pink dice in the mirror.” I thanked her for everything and left in a hurry.

I dialed the number and held my slide phone against my ear. The phone rang a few times and he answered. I said something like, “Hi um, this is [dead name redacted]. You left a CD on my car today.” My palms began to sweat. He replied to confirm that he had in a deep, sleepy voice with an affected Californian cadence. I sighed a silent relief as he apologized for the creepy “stalker move” and detailed how he only happened to see my car because we were in the lot at the same time the other day and he had (of course) noticed the pink dice. Based on absolutely nothing, I decided it was really him.

We made plans for a date a couple days later. He was into music in a way I never would be. He talked to me about the industry and things he hoped to do. We had sex in the dark in between obscure, boring horror movies. Every time afterwards, he would flip on the lights and put a Duran Duran CD into his comically large stereo system, repeating random trivia about them to me. I began to (and continue to) hate Duran Duran, but this was the first time someone had gone from noticing me to wanting me, so while I laid there in the wet spot, I would pretend to be into everything he said in this weird post-coital ritual. For the next few weeks, we had a short, awkward relationship until he eventually broke up with me in a MySpace message after disappearing for four days.

In the 2008 spring semester, I divided my time between two different campuses and focused in a little deeper on school, carrying the shame of my first failed class and first failed relationship. I subconsciously sustained my visible queerness, driven by that deep, undeniable urge to continuously experience myself and my body in a way that felt real.

The first beer bottle hit the hood of my car as I merged onto I-20 West going home. It came from a truck in front of me and I recognized the driver as a man who had been walking to the campus parking lot around the same time as me. I slowed down, changed lanes, kept driving — shaking.

The second one hit my car door in that same semester after leaving the same campus. The third one came at my body as I walked down the sidewalk six months later when I started attending the University of North Texas, about an hour north in Denton. It missed me. Then there was the fist full of coins in the Wal-Mart parking lot later that fall. A man shouted “FAGGOT” at me and a friend from his truck window as we walked to Mister Chopsticks to get food.

By this point, I had been experiencing a steady stream of mild violence in public for about two years, so I started to feign being unbothered by the increasingly familiar assaults even though I fell apart inside each and every time. I began to resent whatever it was that urged me to express my identity, but I didn’t quite know how to stop being this person. Even in jeans and a plain shirt, somehow they all still knew.

In my remaining four years in Texas, there would continue to be more bottles, coins, verbal assaults from passing cars (trucks), and countless cyber-trolls. After I finished my BFA in Dance Performance at UNT, I ditched all of my possessions in my apartment dumpster and moved in with some friends I barely knew in Manhattan. I lived in five apartments in NYC (and part-time in one hotel in Connecticut) over the span of four years before I landed in a dream spot in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, where I shared a building with friends that felt like family.

Throughout my five years in New York, I formed a technique around my visibility. I was unapologetic in the moments when I could be and completely invisible in moments where I felt I needed to be. Though I felt myself becoming a more refined disturbance of public space in a city where I would have hoped I could be more safe in being myself, the onslaught of mostly verbal abuse was relentless. Toward the end of my fifth year in New York, I stepped out of the Kingston-Throop stop on the C line, and as I passed a man on the corner of the next intersection, he shouted that he’d kill me if he saw me on this block again. I didn’t pause, miss a step, or redirect my eyes. I walked on and I never went that route home again.

Several months later, I was being crushed under the undeniable realization that I couldn’t be safely visible in New York City. Even among the Gay community who call themselves Queer, I felt an overwhelming sense of otherness. The gay community didn’t seem to be interested in a femme presence unless it was performed on stage during shows at gay bars.

That April, on a weak impulse, I moved to LA — only to be hit with loneliness like I had never felt before. Around the time of my cross-country move, I began to express to my friends that I didn’t really feel like he fit me very well, and that I hadn’t for a while. I tried on she as I meandered LA struggling through toxic roommate relations, my first bout with genital dysmorphia, and my not-quite-first bout with public violence and suicidal thoughts.

In LA, I no longer tried to stifle my inner urges to express what was constantly bursting out of me as I grew my curls long and began wearing dresses and skirts more often, but my efforts were clumsy and this level of visibility made me ill. I wasn’t ready. I started to form an understanding at this time that all it would take was existing in a certain space and time for something terrible to happen to me, and so I felt terrible in all space and all time. I was breaking down.

After six months in crisis, I moved to Portland, thinking I just needed to find the geographic place where the inevitability of being visible wouldn’t inflame every facet of my life. There, I found a brief romance with a sweet boy named Jordan who was a writer. We spent almost every day together, both of us jobless and depressed, taking turns comforting each other. And though aspects of our sex together felt so necessary, mostly we had the kind of awkward sex you might imagine two sad strangers would have.

Two months later, he found a good job and asked to pause whatever it was we were doing. I, still unemployed and full of emotional wounds, crumbled, even though I knew this would eventually happen. We were both damaged, but he was the one doing something about it every day. I was not in control of my visibility, but I managed to disguise my devastation over our fling ending in a performance of yogi-like wisdom. Jordan and I weren’t in love so much as we were in loving contact. We both needed skin to touch with our own and a sense of belonging that we weren’t getting anywhere else.

Five months into living in Portland, the hikes stopped being therapeutic. One day at dusk as I sat on the couch in my empty house, my heart began to flutter in my chest. My breath came in heaves and my vision spun. This dreaded feeling wasn’t new to me, so I calmed myself down for a moment, splashing my face with water in my cramped bathroom, trying with every ounce of mental strength to talk myself down from this panic. But five minutes later, the panic came back worse and I felt it attacking from that same deep place where all uncontrollable urges come from. My body, my mind, my spirit — every cell and atom that comprised who and what I was spasmed and quaked.

I wailed out animalistic sobs between sharp inhales, and though I understood that a panic attack probably wouldn’t, I wished for it to kill me.

Two weeks later, I abandoned my lease and retreated into the safety of my mother’s house back in Fort Worth, Texas. Back to the town where I began to notice myself and began to notice how others observed me. I began to heal.

In August 2019, I turned 29. The cliche blessing of birthdays is that they give me an opportunity to clear my mental cache. I wore a peacock kimono as I sat in my parent’s backyard smoking a spliff and watching the dog hunt a squirrel that wasn’t there. The sunlight was heavy like I remembered from years before. I thought about what might be next.

II. C.Q.

Tom of Finland, known for his caricature-like depictions of gay male bodies and sexuality, rose to prominence at a time when gay men decided they could benefit from a re-branding. The straight monoculture in the 60s was still in it first moments of even acknowledging the societal binary of Straight and Gay and, as is echoed today (though much less so), gay men were seen uniformly as sissies.

Around this time when the sexuality binary began its spread through our language and morality-sphere, assimilationistic gay men began calling themselves “Gay” rather than “Queer” as they had done in earlier decades. “Queer” insinuated that there was something inherently different about men who loved and fucked other men.

The rejection of this label would last into the early 90s, when it would reemerge as an identifier for those of other genders and/or other sexualities who interact with the political and social world in radical ways.

Tom of Finland was a surrealist illustrator with a fixation on cartoonishly gargantuan dick bulges stretching perfectly tailored denim or leather pants and hyper-masculine dude-fucking. The (white) men in his drawings were hairy-chested and overflowing with muscles, aggressively impressing the point that being gay didn’t mean being soft and feminine, it meant being an alpha male inside another alpha male.

These days, I find that I have to momentarily forgive the overwhelmingly toxic levels of performative masculinity in his work (as well as his admitted and overt self-indulgence) in order to see the good that Tom’s work brought into the world at a time of intense governmental censorship. In the ‘60s, the U.S. government had strict anti-obscenity policies that forced publications that would otherwise be pornographic to disguise themselves as physical fitness and health magazines. Tom’s work was featured on the covers of magazines under the “beefcake” genre, and its social impact, both positive and negative, eventually led to the Supreme Court trial of MANual Enterprises v. Day, wherein the Court ruled that the nude male body was not inherently obscene, which was a win for gay men and a definitive step out of a large degree of oppression. The ripples of this case eventually gave way to the availability of porn as we enjoy it now, but more importantly, it empowered gay men to be more gay more of the time.

Of course, there’s nothing wrong with appreciating highly technical, impactful, and distinctly stylized artwork that also sparks arousal, but gay men continue to worship the work of ToF as if it is as radical now as it was then. As I scroll through the varied hashtags of queer art through Instagram, I see the echoes of his work in the overwhelming amount of muscular male bodies done by (mostly) young male artists. In the context of Instagram (especially right now), censorship is a big deal since disciplinary actions seem to be unfairly swayed toward all non-straight people. But as trans and non-binary artists attempt to raise their voices about an opportunity that never existed to them stretching further out of reach, their voices get lost among the influential cis gay men who are lamenting a once (socially or monetarily) lucrative opportunity that is being taken away from them.

The inequity here becomes further disparaged by the widespread use of the word Queer by gay men looking to define themselves as more subversive and equally as oppressed as those of us who don’t have the privilege of being able to move in and out of Visible Queerness or Otherness. It has become popular for gay men to think of the word queer as synonymous to all who fall under the LGBTQ+ umbrella, but the danger there lies in attempting to equalize all of us before we’ve actually become equal both politically and in our local communities.

There is no clear way to lay down borders between labels of identity, but whereas “Gay” has taken several steps toward normalcy over the decades since the 60s, “Queer” still feels like an outlier. And though gay men are not always safe in all parts of our country, where they experience violence, trans people are murdered.

III. Heard them coming, Saw them enter

Fred is magical. I met them at a turning point in my emotional and mental health when I began to feel like a person again. I had just moved back to my hometown in Texas, and one night, while I was dancing for my absolute life at a small hotel party, they passed by me in an enormous fur coat. I knew them from Instagram and reflexively reached my hand out to get their attention before they were gone.

As they turned toward me, I noticed the rings on every finger, the low-hanging necklaces, and the blue velvet chunky-heeled boots. I gawked to them about their ensemble and they briefly explained to me that it was just their daily armor.

There, in the middle of the dance floor surrounded by moving bodies, we paused there understanding each other.

It’s rare for me to find someone so similar to myself. We are both slight-statured with long brown curls, impeccable style (though I will always aspire to their level on this), and big non-binary energy.

A month later, Fred and I went to the Modern Art Museum in Fort Worth’s Cultural District, just a mile or two away from the famous stock yards that give us our nickname, Cowtown. Fred had already been through the exhibit just before I got there. It was called “Disappearing,” and they gave me a tour through what they had seen, guiding me through the context of the artists’ work and respective lives. In between telling me about pieces in the exhibit, they asked me questions about my recent travels and my early life. With fellow queers, the early life always comes up, as it’s usually our first available common ground.

After walking the gallery and sharing memories of being a kid in this same museum, we found our way to the sunlit cafe that overlooks the reflecting pool. It was amusing to remember being thirteen, back when I thought of this cafe as a place for very fancy adults. It made sense to be going in for the first time with Fred.

We ordered food and I ordered a negroni as Fred told me they weren’t much of a drinker anymore. They continued to ask me questions about my experiences with family and living outside of Texas, and I found myself slowly spilling intimate details of my identity crisis in New York City to them, about how I discovered I might not actually want to be a dancer after having studied dance since adolescence. I told them about feeling unsafe and unsettled in New York, about my relationship with an artisanal butcher, how I overcame my trauma with my real-life evil stepmother, and how I was still becoming myself after a long bout of loneliness and depression on the west coast.

Afterward, we took my stepfather’s car to the water gardens, where Fred told me anecdotes about the architect that designed them. I was enamored by their abundance of knowledge and maybe a bit self-conscious about my lacking, but Fred seemed content to be the one leading the way while I talked about all of the things that were churning inside of me. When the light started to become a warmer orange around us, our energy settled and it was time to part ways.

The next time we saw each other was a month after at the same museum, and Fred had brought along two of their friends, Blake and Pierre. Like Fred, they exuded a visible aura of queerness. My nervousness of meeting new people dissolved quickly into conversations about visibility and art as we moved out into the grass where we lounged on cement chairs overlooking the water. Fred took a photo of the three of us against a wall where Blake and I looked stoically content while Pierre stole the shot with their smouldering energy. Being in a photo with them taken by Fred felt good in a way I hadn’t felt in a long time. It was a simple, effortless moment that sparked a sense of belonging and roused some deep dormant part of me.

At home later that day, I looked at the picture again. In it, I saw people who exist creatively, not just in the sense that they create profound artwork, but in the sense that surviving in its most general mundane sense, for them, must be done creatively. They found each other and held each other close and that is how they dealt with the exhaustion that living creatively brings, and they were allowing me to become a part of that huddle. The dizziness of feeling lost began to settle.

Two months later, Fred brought a group of eight beautiful queers together to celebrate my birthday in August, and though I knew Fred, Blake, and Pierre, I was in shock that five complete strangers wanted to come together for me. I was fortunate not to be the last arriving because it meant I could watch the remaining others enter the restaurant. A queer person entering any kind of social gathering is a mix of a dancer entering the stage and a gladiator entering the arena.

Sebastian and Colton could be heard clacking rhythmically across the tile through the more crowded entrance of the restaurant wearing short dresses and heels looking like they could be the stylists for Sex and the City and Mars Attacks. They were stunning and I was elated. Misael entered softly in a bucket hat and overalls and all of his gentle beauty. For two hours we sat at the table fawning over each other. At the end of the meal, they all sang “Happy Birthday,” and it was the first time in my life I didn’t want the song to end.

For a night, I was with a group of people who showed me love and understood my story without me having to tell it. Now, when we are together, we get the chance to celebrate each other for the things that make us feel unsafe elsewhere. Finding each other is never guaranteed and it can feel like the most impossible task, but I was lucky this time, because Fred found me.

IV. Epilogue

No matter where I go, I will always come out of me. I may flow freely from myself or I may topple dams I build in my own way, but one way or another I will always emerge lilting through doorways, billowing skirt in the wind, stomping through hallways with cute boys and moms who are nice to me, or leaving trails of flower petals down subway steps on blocks where people have promised to kill me.

It’s unclear when exactly it happened, but somewhere along the way to this moment, I became my biggest indulgence. That feels like innocence, though, in a way I’ve only recently come to understand it. Whereas vulnerability feels like a directive force of control, the innocence it takes to live visibly as yourself, to evolve the language of identities, and to survive creatively feels like an atmosphere you choose to live under, and it takes a will of absolute stone.