“Red Book I”

“Experiences in the Desert”

“Red Book II”

“The Castle in the Forest”

Artist Commentary

1. IMPETUS

The call for this issue of The Seventh Wave asks: “What are the ways that we have to accede to the demands of society, and how are we finding ways to hold onto who we are?” This struck me originally, and strikes me still, as a crucial, yet impossible, question. As I created the art assembled here, I was thinking a lot about the permeable boundary that exists between society and self and the impact of that on the physical body. I was also thinking about the amorality of shame, the constructed and ever-shifting parameters against which our bodies, actions, and beliefs are measured.

As a writer who is also a visual artist, I often process my thoughts in a combination of text and image. It’s rare to find myself creating within the realm of visuals alone, and yet, this is where I found myself after The Seventh Wave’s Bainbridge Residency. After three beautiful days of reading, dialoging, workshopping, and note-taking alongside other writers, language surrounded me everywhere I turned: cozy, but a little claustrophobic. I needed something new to get at what I felt growing beneath, beyond, outside.

In my bedroom at the residency, splayed open on a low table, was Carl Jung’s Red Book, which showcases the results of Jung’s self-experiments in what he called “active imagination,” his attempt to translate emotions into images. I was immediately captivated by this giant book’s hybrid swirl of calligraphic pen, multicolored ink, and gouache paint, and over the course of the weekend, mostly late at night, I absorbed the text, flipping the pages of its accompanying English translation.

One sentence from the chapter titled “The Castle in the Forest” stuck with me in particular: “If you remain within arbitrary and artificially created boundaries, you will walk as between two high walls: you do not see the immensity of the world.”

If you remain within arbitrary and artificially created boundaries, you will walk as between two high walls: you do not see the immensity of the world.

—Carl Jung

The quote spoke most immediately, in my mind, to the work of my fellow residents. I thought of Callum Angus’s short story “Rock Jenny,” D.A. Navoti’s essay “Half-Orphaned,” Courtney Young’s short story “All That Remains,” and Yasmin Boakye’s piece “after (or, nine beholdings).” In their willingness to acknowledge and trouble artificial lines that constrain humanity, identity, and place, these writers speak to immensity. What I feel in my chest when I read their work is that expanse.

2. DISCOVERY

I’m back from the residency on Bainbridge Island, and all the women I love and admire are talking about dance.

Patrycja describes, over tea, a dance recipe she sends to pen pals living in solitary confinement. The steps to the dance are both physical and mental in nature: Press both of your hands together strongly, imagine the room is filled with light mist.

S— tells me that her daughter has qualified for the world’s most prestigious ballet camp, but she can’t afford to send her.

After a long flight, Katie recommends Dance Church.

Moeko says: “If we look at it long enough, movement itself contains stories.”

Carina writes: “The backup dancer is the star’s shadow side, the constant reminder of how precarious her visibility really is.”

I write in my notebook, next to the sketch of an eye (my go-to doodle, my art tic): What of dance remains in a still image?

Wind unfastens blooms from the star magnolia, creating a carpet of white rot.

While I’m at the store, someone rakes the rot away.

What of dance remains?

All these little disparate moments feel like a meditation on the precarious power of women’s bodies. I see it, feel it, hear it everywhere I go. This is the rhythm, lately, of being alive. More wind.

3. PROCESS(ING)

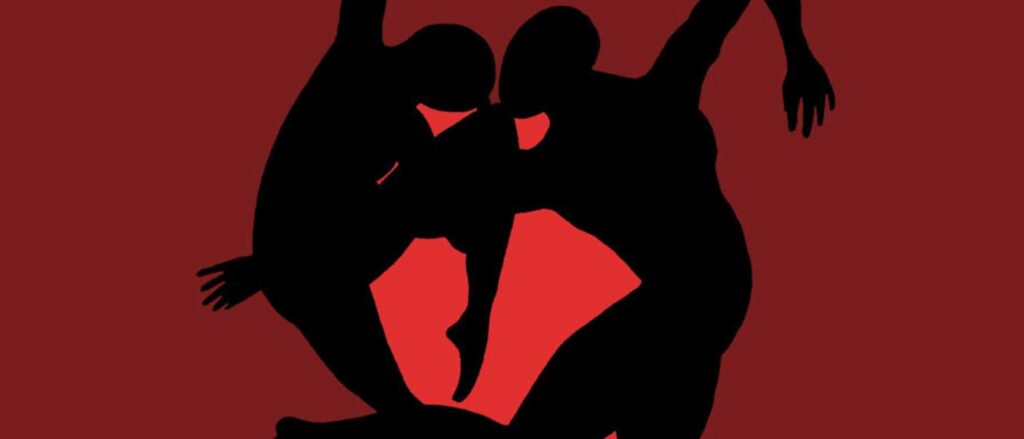

While I’m thinking about all this (power, precariousness, women, dance), I encounter the poem “Mirrors” by Alan Shapiro. As I read, I see the flash of a moving image in my brain, bodies sprouting from the same point, proportionally distorted in various, mutating ways.

In an attempt to understand the image more fully, I decide to scale the high wall (to continue Jung’s earlier metaphor) separating poetry from other forms of art.

What’s lost for me, I think, in staying within the artificially constructed boundaries of what constitutes a poem, is the extension of thought in directions that contend, authentically, with languagelessness. While the walls around poetry as a genre can provide focus and helpful constraint, to never venture outside those walls is to warp and shrink the scope of poetic inquiry in a way that feels stale and unhelpful at best and at worst, violent and deeply untrue.

As to not simply leap from one tall-walled hallway to another, it feels important to detail the chain of translation that led to the final pieces assembled here.

First, to get closer to the image that flashed in my mind, I go to dance. I spend time with videos of dance and then, shortly after, with stills of videos of dance, which I scroll through on my laptop until something about the arrangement of one halts me.

When this happens, I take out my pen. I do not draw the photograph exactly — or, rather, not as exactly as I could. The drawing of the photo of the dance is approximation and translation. Like Jung in Red Book, I am trying to translate the emotions prompted by one image into an image of their own.

Once I have a small collection of drawings like this, I scan them. Only recently did I learn how this technology works. An angled mirror reflects each page I set down on the scanner to another mirror, which splashes the reflection on a lens, which filters the image into miniscule, light-sensitive diodes, creating electrons of varying configurations. I love thinking about what the literal reflections and energies transferred in this process have in common with the metaphysical reflections and energies in the final product — it fascinates me how they function similarly, using slant angles and gaps.

Poets sometimes speak of electricity in poems. Of heat. (“Where is the poem hot?” Terrance Hayes once asked a classroom of poets, and I raised my hand).

Most scanners speak a common language called TWAIN, which serves as an interpreter between the scanner and where the scanned image lands. To assume it’s an acronym would be both reasonable and incorrect; it comes from the saying “Never the twain shall meet,” a British phrase first used (says Google) by a trumpeter of racist imperialism to bemoan the chasm of understanding between people in colonizing countries v. colonized countries.

In digital space, I arrange and rearrange the drawings I’ve scanned in overlapping pairs. I rotate and adjust until they become a new figure, more singular than double, and this new shape gives off energy I can feel.

Experimentation with red coloration begins as an explicit homage to the Red Book. Instantly, the addition of this color scheme snaps the piece (which has been, up until this point, entirely black and gray) into new context for me. Suddenly I’m thinking about organs and wombs: the hidden, bloody, multi-dimensional landscape of our bodies. The metaphysical process of active imagination is returned to an intimate, visceral space. Not a high-walled structure, but one that is amniotic, permeable, life-giving.

Until now, my visual art has been defined by a stark lack of color and meticulous detail: the tracing of what appears to be every single hair sprouting from a head, braided sinews in muscle, the texture of a topographical map. Now, suddenly, I’m loving my subjects from a greater distance, focusing my attention on shape, form, gesture.

What do we lose when we celebrate this sort of figure? I wonder. What do we lose when we don’t?