IN THE SOVIET RUSSIA OF THE 1980S, MY MOM CHOSE NOT TO TELL ME WE WERE JEWISH.

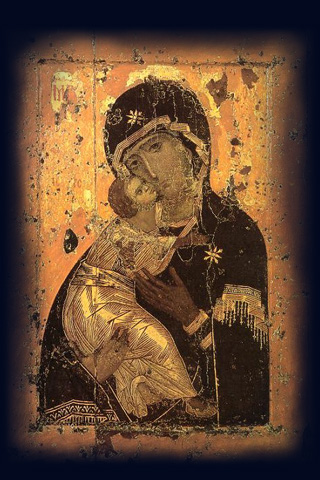

The icon was taped to the side of the wardrobe that abutted the foot of the bed. It was a single sheet of matte paper that curled at the sides with an image of Mary holding baby Jesus in her arms. The baby was large, with an oddly shaped head — it was flat at the top with a high forehead and low, puffy cheeks. The baby’s expression was difficult to read. Sometimes it looked blank, at other times bewildered. His brows were furrowed and the eyes sat close together. He held onto his mother’s neck with his right arm and extended the left toward me with a gesture somewhere between pointing and greeting.

After the divorce and getting too big for my crib, I shared the bed with my mother in my grandparents’ apartment. Gorbachev may have been announcing reforms on TV, but the housing shortage was still in effect. If you wanted an apartment, you had to apply to the government who took decades on housing projects, so most families lived three or four generations together. Dad had moved back in with his parents.

I had a strict bedtime, so I always went to bed at least an hour before Mom. I would hear the dull mumbles of the TV my grandparents were watching through the bedroom walls. Mom’s evening pastime was chatting on the phone with friends. After we all ate dinner she would disappear into the back room — a converted walk-in closet in my grandparents’ bedroom that served as Grandpa’s retreat during the day. Surrounded by shelves of plastic boxes filled with household tools, welding equipment, unrecognizable metal and plastic parts that had come off of failed machines and been rearranged into new objects, Mom would sit cross-legged, dangling a slipper on her foot and winding the coiled phone cord around an index finger for hours. On some nights her laughter rang through the house. On others, the door was closed and I could hear quiet murmurs when I came to say goodnight.

In bed, I lay next to the wall fingering the patterned rug that hung there, often taking a long time to fall asleep. I slid my legs up against the rough surface and lay bent at a 90-degree angle against the wall staring at the ceiling. When this game got boring I rolled my head and eyes to see if I could make myself dizzy. I lay the blanket underneath me and positioned myself at one end, grabbing and rolling myself in. I rubbed my eyes hard with my fists to see the pattern of light that inexplicably illuminated the darkness. Tiring, I stared at the icon that hung opposite me on the smooth wood surface of the wardrobe, puzzling over the two faces looking back. Madonna and child. Where the baby’s face was strangely proportioned, Mary’s was smooth and beautiful. All of her features were narrow — slit eyes, a long slender nose, and thin pressed-together lips. She had a pointed chin with a downturned crescent dimple and perfectly angled cheeks — not so sharp as to make her look angry, and not so sluggish and low as to create an air of dissatisfaction. Her face leaned toward the child, but looked out from the image, as though watching me.

I had seen icons in churches my mom often took me to. Every summer after age three, due to my frequent cough and lung infections (probably resulting from our proximity to factories on the outskirts of Astrakhan), Mom and I would travel on adventures to greener places. This was done on the advice of doctors and embraced with gusto by both me and Mom. Without Grandma’s strict rules of behavior and her frequent questions and instructions, we roamed green fields in resort locations like the Pushkin Mountains — the Russian author’s estate and surroundings — carefree as sisters. We made flower wreaths, lay in the grass, rolled down hills, and climbed hay bales. We got lost in the woods, caught in the rain, climbed muddy mountains and squeezed through brush for shortcuts. We picked aromatic dwarf wild strawberries, turgid black blueberries, prickly wild raspberries, black and red currants that looked like jewels growing on a vine, and furry, tuft-tailed gooseberries. We sucked out the honey juice from the thistles of clover-flowers after Mom showed me how.

Everywhere we went in the summers there were churches of all shapes and sizes to visit. Some were great mounds of white stone capped with gilded, green, or red cupola — these were usually in nearby towns and cities where we would take excursions during our summer retreats. Some were wooden and looked more like log cabins, only accessible by trails in the nearby forests. But no matter what the church looked like on the outside, a special feeling took over as we approached. Mom held my hand and we would grow quiet, advancing slowly toward the cool, dark interior from the outdoor light.

Inside, women in kerchiefs prayed in pews, while some of the most devout knelt by the altar under the cross. A few bent over the votive stand extending lit matches over lazy wicks. No matter the size of the church, the walls were always covered with icons — faces surrounded by gilded halos enclosed in shiny metal and carved wood frames.

We never prayed nor lit any candles. Instead, we would wander the aisles peering into the faces on the wall. I don’t know what we were looking for. I was not particularly interested in the images, but I wanted to understand why Mom was.

It reminded me of being in a museum, but you had to be even quieter in case God really existed and minded the noise, and also out of respect for the people praying. Mom never talked about God like she believed in Him, but she had had a piano professor at conservatory who became a priest after his grown son died suddenly, and she talked about him often. She said that he had been the only safe person in conservatory to ask questions that had been bothering her since she had visited the Hermitage in Leningrad. At the time, she understood that religion was backward — as she had been raised to believe under Communism — but wondered why people were not allowed to learn the religious stories behind works of art in order to understand their cultural history. And why, when some of the world’s most beautiful music, like Beethoven’s, was created to praise God, were musicians like her forbidden from studying the texts behind these composers’ faith in university? Her professor lent her his Bible — a piece of contraband — so she could read those stories for herself.

On the way out of each church, I would inevitably stop at the desk in the corner lined with small remembrances for sale. There were always cards with saints’ faces printed on them and short prayers written at the bottom. Miniature and larger framed icons with strange and ancient features like the one in our bedroom sat among crosses of different designs and sizes laid out neatly in rows, chains stretched taut as bows. Both my dance partner Alyosha and my best friend Zhenya wore such tiny crosses on chains around their necks. You could even see them from far away because of the way they glistened in the sun. Once I started school, I began noticing that other kids had them too, as though they were part of a special club.

“Too expensive,” Mom shook her head as we left each church and its crosses behind.

Like many families around me — even cross-wearing ones — my family was simply not religious. At home the biggest holiday of the year was New Year’s, and in addition to this there were parties almost every weekend for birthdays and anniversaries for someone among the extended family. We celebrated a lot over lavish feasts of classic Soviet fare, but none of our celebrations included religious rituals. Even the tree we decorated lovingly for New Year’s had no religious or symbolic significance. I looked forward to hanging fragile glass ornaments on our plastic tree, all wrapped in lights and tinsel, every year, and I loved waking up early in the morning on January 1st to presents, but there was never any conversation about why we did these things. To my mind, we did them because we had done them before, and the memories of those other times were something to celebrate.

My grandparents were raised as Young Pioneers — a mandatory national communist organization that served as the core of children’s communal life. At the Pioneer meetings, kids learned that the only truth came from the Party and that religion was something silly people believed in the past — until the revolution. When Grandma was a girl, she and her sister used to giggle peeking from behind the door as they watched their father bowed in prayer.

It was not until the summer between 2nd and 3rd grade, when I turned eight and several years into our travel tradition that Mom said any more on the matter of the cross. We were on an organized bus trip to a log church in the woods of the Yessentuky Mountains. Walking out of the church’s cool interior, the sun blinded us before our eyes adjusted to daylight on the leaf-strewn path. A few steps outside of the church stood a wooden kiosk that seemed like the larger building in miniature — lined with the usual wares. Only this time I spotted a tiny wooden cross, quite a bit cheaper than the gold and silver ones next to it.

“Mom, look!” I pointed. “This one’s not expensive!” I looked deep into her face. “Please!”

She did not answer immediately, but examined the cross I indicated. “Hmm, do you really like it? I think it’s kind of plain.”

“I do! I really do! Mama, please? Why not?”

Again, she did not look directly at me. “Come on, we have to get back to the bus.”

“Why can’t I have it?” I stomped my foot.

Mom shifted and turned her head to look over her shoulder. Then she turned back toward me, “Look, it’s not for everyone. It’s not for us, you understand?”

With this, she turned around and started walking away, and though for a minute I stood watching her go, refusing to follow, I ran after her as soon as she disappeared behind the trees.

When we returned from our adventure that summer, the denial still puzzled me. We had the icon that hung in the bedroom, I had a tiny baby blue children’s Bible (legalized after Perestroyka), and many records of Bible stories, so I didn’t understand why this one object — a little cross, which seemed to belong — was different. I kept poking at Mom with what I thought were subtle questions: “Have you ever worn a cross? Why not? Did Grandma not let you buy one either?”

Then one day just before the school year started, she sat with me on the edge of our bed and told me the reason I couldn’t have the cross — it was just two words: “My Yevrei.” I cannot say I remember this conversation now. All I have is the sitting on the edge of the bed, the words, and then tears that I could not stop flowing.

Plenty was said about Jewish people behind closed doors at the time, and sometimes out on the street. It was in the bazaar where I often accompanied Grandma to buy our vegetables that I first overheard the word “Zhid,”the Russian version of kike. I knew it was something disgusting because there was a grimace that went along with that word, but I had no idea what it meant, nor that it could be used against me. When I found out that it could, this only brought with it a slew of other questions. What is a Jew, anyway? Why do people hate them? Why did I have to be born one if so many people hated us? Why didn’t Mom tell me before? Why don’t we have Jewish things but Christian ones instead? After that first conversation with Mom, the heaviness was smoothed over by the feeling that she had shared the secret with me. Not just any secret — a big one.

And because it was a secret, I needed to tell someone. I did not go to my best friends Zhenya and Nellya — I don’t know why. I chose Andrei, a friendly bucktoothed and freckled boy in my class of 30. The previous year he had told me a secret he knew — that it was another Andrei in the class who had hidden my shoes as a prank, forcing me to walk home in embarrassing adult clogs found at the school nurse’s office. As a result of this revelation, my shoes were restored, the perpetrator punished, and I concluded that not all boys were bad.

One day early in the school year and soon after my conversation with Mom, my classmates were doing tumbles on blue mats for gym class in a windowless room at the school. After both Andrei and I had had our turn and were sitting by the wall waiting for the remaining kids to go, I slid over to him and cupped my hand over his ear.

“I want to tell you a secret.” He leant into the words. I could tell his interest was piqued.

“What is it?” he said.

“You can’t tell anyone, ok? It would get me in trouble. My mom just told me.”

“Okay,” he whispered back, nodding in alliance.

“Alright then…I’m Jewish…” I whispered.

He turned and looked at my face quizzically, “Huh?”

“I’m Jewish!!” I repeated, my heart about to bust through my ribs.

He didn’t answer, just cocked his head. And suddenly we were being herded back into the changing rooms and that was that. I didn’t know exactly what reaction I was hoping for, but this was not it.

A few weeks passed and Andrei was acting as though I hadn’t ever told him my secret. I hung out with my girl-friends and he hung out with his boy-friends. I kept looking for signs of change in his face, but it truly seemed like he had not understood what I had said and decided to forget about it.

This was fall, the time of year for the Olympiads — class subject competitions in schools across Russia. Each year select students from grades three through ten would undergo a series of tests and tasks to determine the district, regional, state, and national winner for each eligible grade and subject. One day in Math class, there was a buzz that the teacher would be announcing the winners of the subject’s district winners.

“In third place, Oleg B.”

“In second place, Anya F.” (That was me!)

“In first place, Nellya T.”

She began to clap, signaling to the rest of the students to follow. Nellya, who was sitting at the desk in front of me, turned around and beamed at the mention of our names. I was bouncing up and down in my chair as I clapped, a huge grin animating my face. Math did not come as easily to me as Russian, so my progress was the result of struggle, Grandma’s attentive scheduling of my homework time and sessions with Grandpa in his back room retreat to work out sticky problems. This was a true victory! But through all of the enthusiastic clapping, suddenly a whisper from behind entered my field of hearing. It was a girl’s voice: “So excited you’re about to let out a fart, huh Jew?” I fell back down into my seat, frozen. It was as though I had been thrown out of a car whipping around a sharp turn. The room darkened, but the applause kept ringing around me.

Anya L. was her name, a girl with short, wispy blond hair tied up with a bow. Her eyes a piercing blue. That day she began following me home after school, pulling my braid, tripping me, and calling me a dirty Jew. She called Zhenya, who often walked with me, a rat for being friends with me.

I came home and told Mom what had happened.

“Have you ever heard of Ghandi?” she said, “Or Martin Luther King?”

“Yes, I think so,” I lied.

“Well, when their people were being called names, they did not react by hurting the name-callers. They just knew in their hearts that these were lies and they had their dignity. So you just ignore her and she’ll stop eventually. Jesus also said to turn the other cheek…”

The last thing I wanted was Mom’s plan of inaction, featuring Jesus. I wished Dad would swoop in and protect me instead, but he and his parents and sister had emigrated to Israel that summer — another clue as to the timing of Mom’s revelation.

What I wanted, at the very least, was permission to hit Anya over the head, hard, or to kick her or push her down. But I was scared and what Mom said made it easier somehow for a while, knowing it was the other Anya’s problem, not mine.

But my patience and silence seemed only to egg her on. Where she used to follow me only until our paths home diverged, Anya began to pursue me even into my own neighborhood, only leaving when we were in sight of my apartment building. Soon school became a constant expectation for the next putdown. Yet, no one but my two best friends seemed to know what was happening. And Mom kept repeating her advice until I stopped asking.

So one day Zhenya and I devised our own plan. When Anya followed us, instead of parting ways to go to our separate houses, we went to Zhenya’s house together. It was in a different part of town and we knew Anya wouldn’t know the neighborhood. After a while we ran ahead and disappeared behind the squeaky wooden gate that separated the house and garden from the street, leaving Anya to wander on her own. We waited breathlessly behind the fence for several minutes, our ears to the peeling paint and wood, until we were sure she was gone. I peeked, checking both ways, and walked home carefree and triumphant.

That night we received a phone call from Anya’s mom. She was calling all of the students in the class because Anya had not come home that day. I couldn’t believe what I was hearing — could it be our mission had been even more successful than anticipated? But what if something terrible had happened to her?

Though she was back in school the next morning, Anya seemed a little bit less sure of herself than usual. She even ignored me for a while. But after lunch, she was at it again. It was break time right before math class and we were about to settle down for the lesson when she said another of her hateful remarks. She was leaning against the black top of her desk in the back of the room, her notebook and bright new plastic pencil case next to her. I was standing between her desk and my own watching the smirk spread across her face.

And then something happened. I didn’t think. I just picked up the pencil case and I smashed it against the floor. Pens, pencils and the pink and blue lids scattered across the classroom with a racket. The other kids were still chatting as if nothing had happened. For the first time, Anya looked scared. And then suddenly, she yelled, “Look what you did! You broke it! It’s a new case and you broke it!”

I could feel my ears burning and my neck itching. I was breathing as hard as I did during PE sprints. I prayed without destination for strength.

As loudly as I could muster I sputtered, “Leave. Me. Alone.”

It was a long time before I told Mom what I had done.