“How did you first get into photography?” my editor Isaiah asked when we met in person in Brooklyn this past September. I was suddenly reminded of a humid summer day in 2022, when my friend Lauren forgot their disposable film camera in my apartment in Durham. Both from China, we had just met through Chinese queer feminist networks in New York and were excited about doing some local organizing in Triangle area North Carolina.

That day, along with two other activist friends, we feasted in my summer apartment with fresh homemade foods: twice-cooked pork 回锅肉, steamed pork with rice flour 粉蒸肉, broccoli stir fried cantonese sausage 西兰花炒腊肠, braised chicken legs 红烧鸡腿 and roasted bone marrow 烤牛骨髓. I didn’t have a proper dining table, so we had to squeeze all the plates and bowls on the wooden tea table in my living room. The political precarity and isolation we felt in the (so-called) U.S. made this gathering especially precious. We took photos of the lovely time and laughter we shared, amazed by dramatic flash of this small plastic camera that Lauren endearingly called “小绿” (little green).

Little Green blended into my dark green couch so well that I only discovered it after my friends had left. As I expressed concerns about how to get it back to her since we were two car-less people living thirty minutes away from each other, Lauren proposed: “How about you just use the rest of the film? It will be like a photo diary exchange and you can give it back to me next time we see each other.” A couple weeks later, Lauren came to see me in Durham again. We used the last two films for selfies, and Lauren brought the film to Southeastern Camera (a local film shop) to develop.

The weeks of anticipation and excitement made receiving the photos feel like opening a time capsule. Looking at the photos now, I can still remember the warm taste of budding friendships.

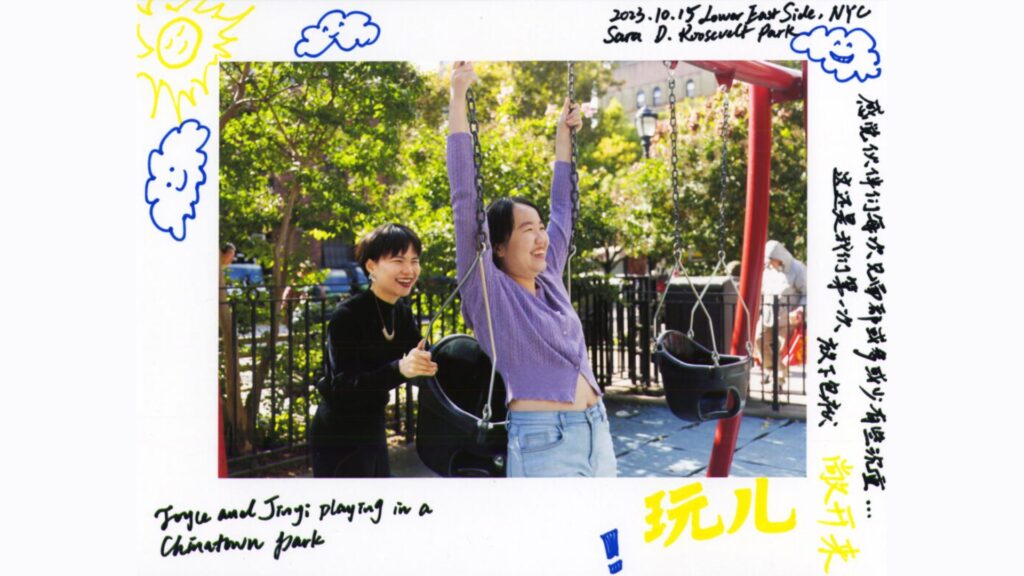

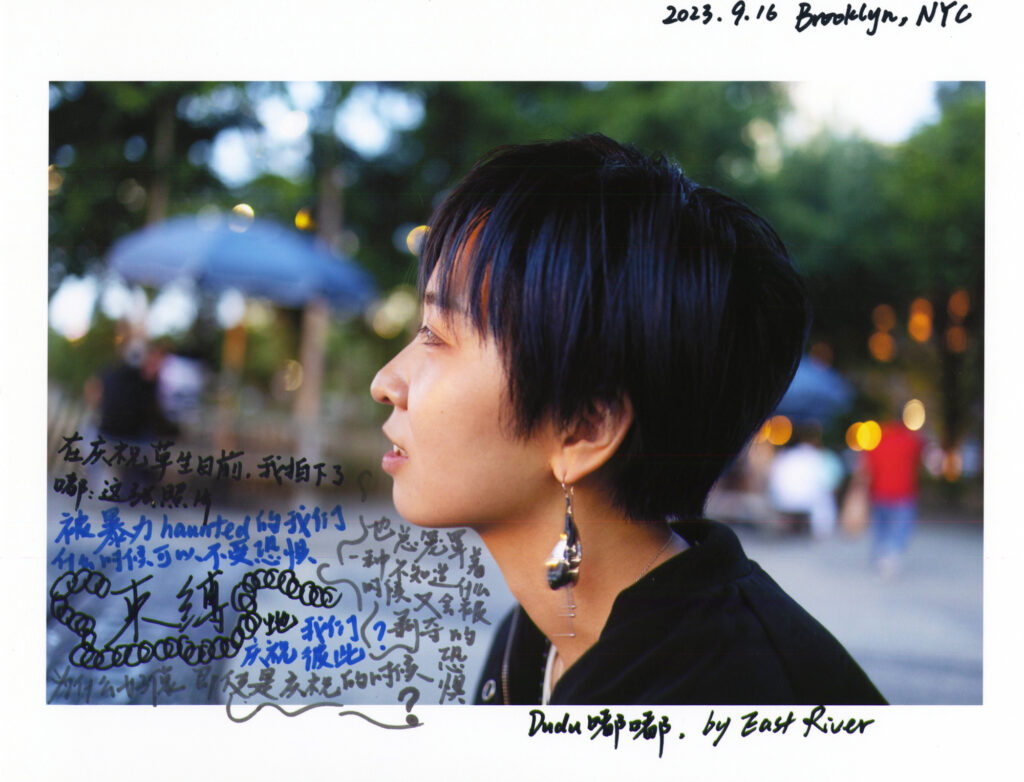

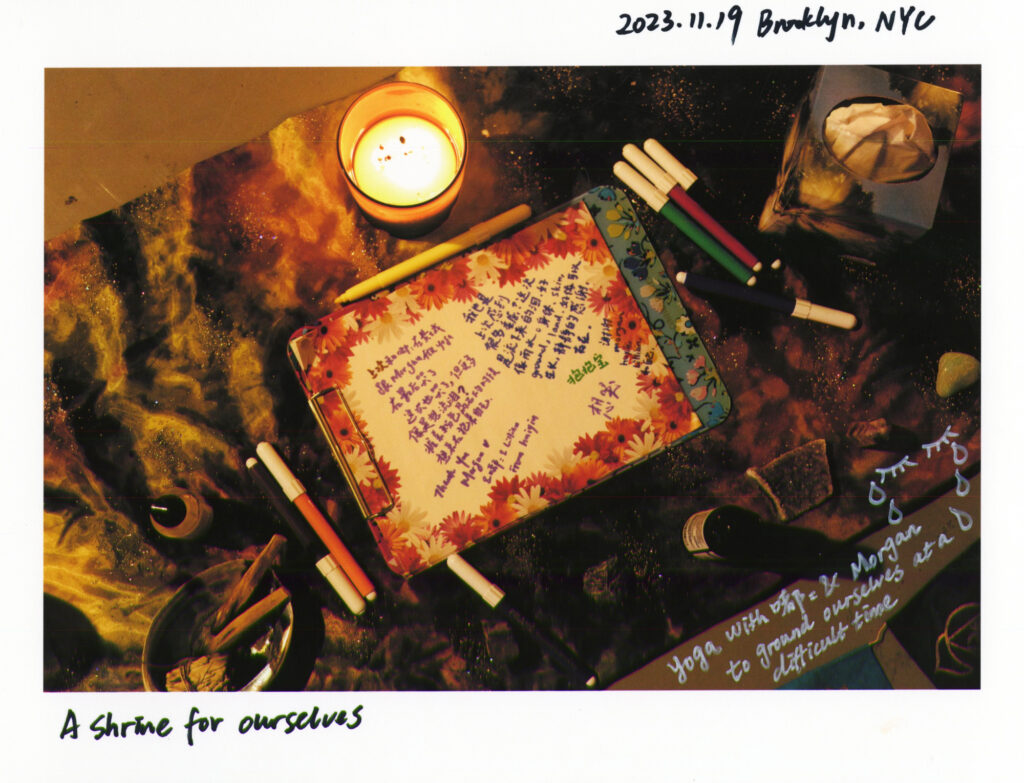

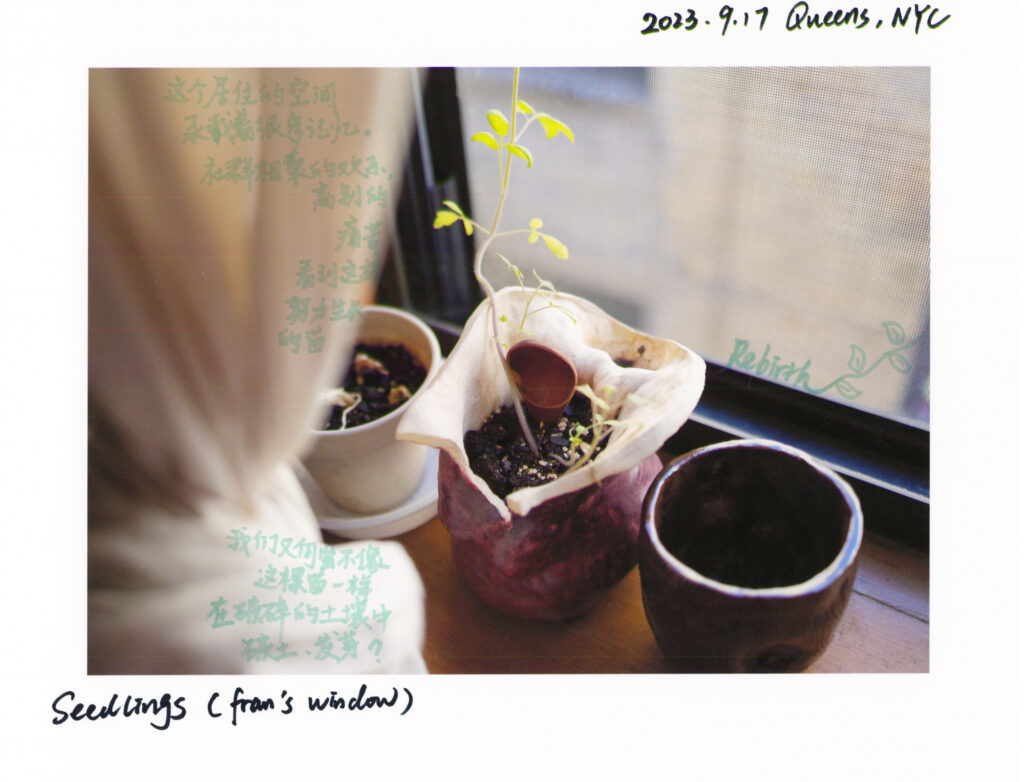

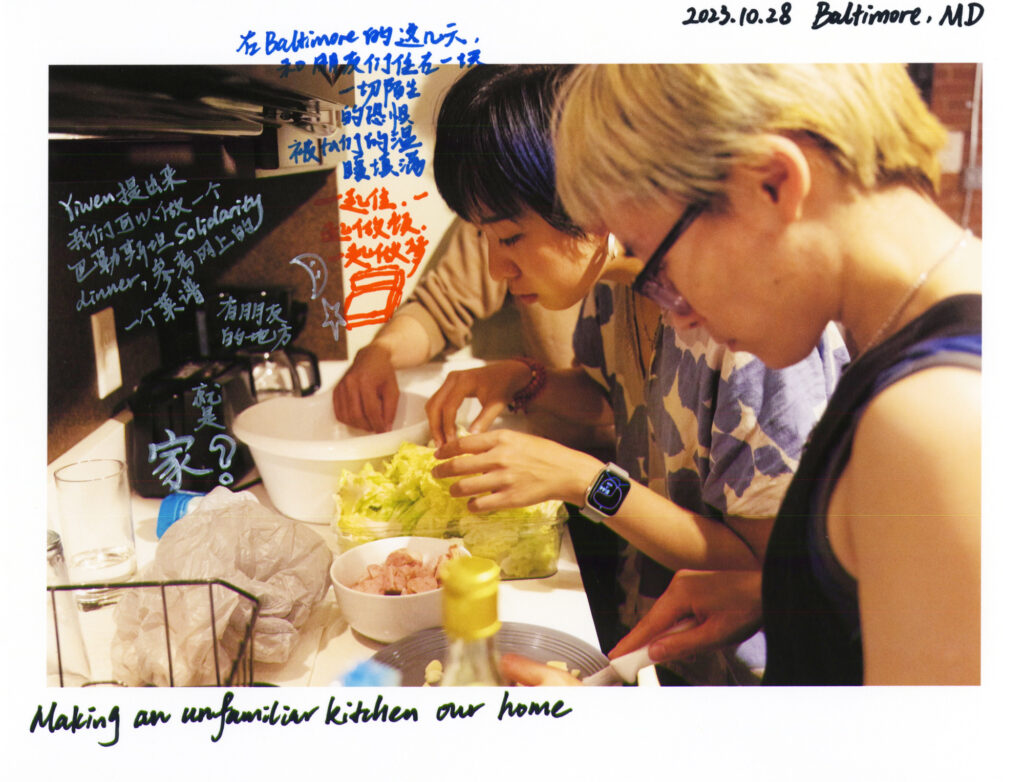

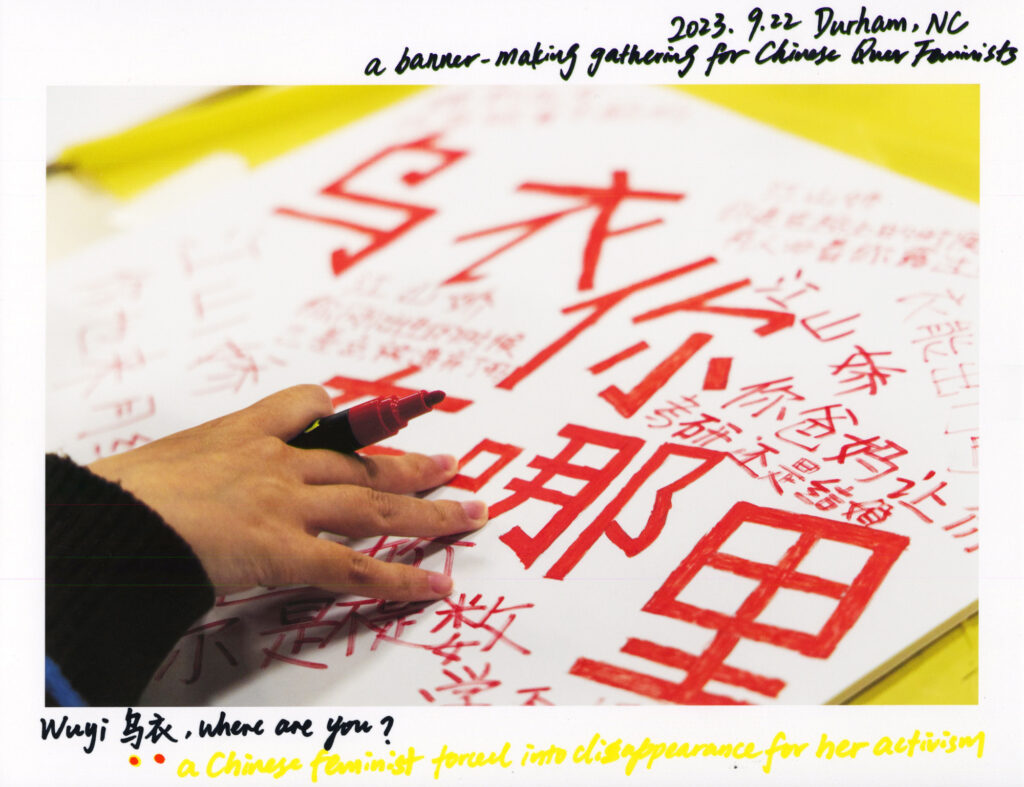

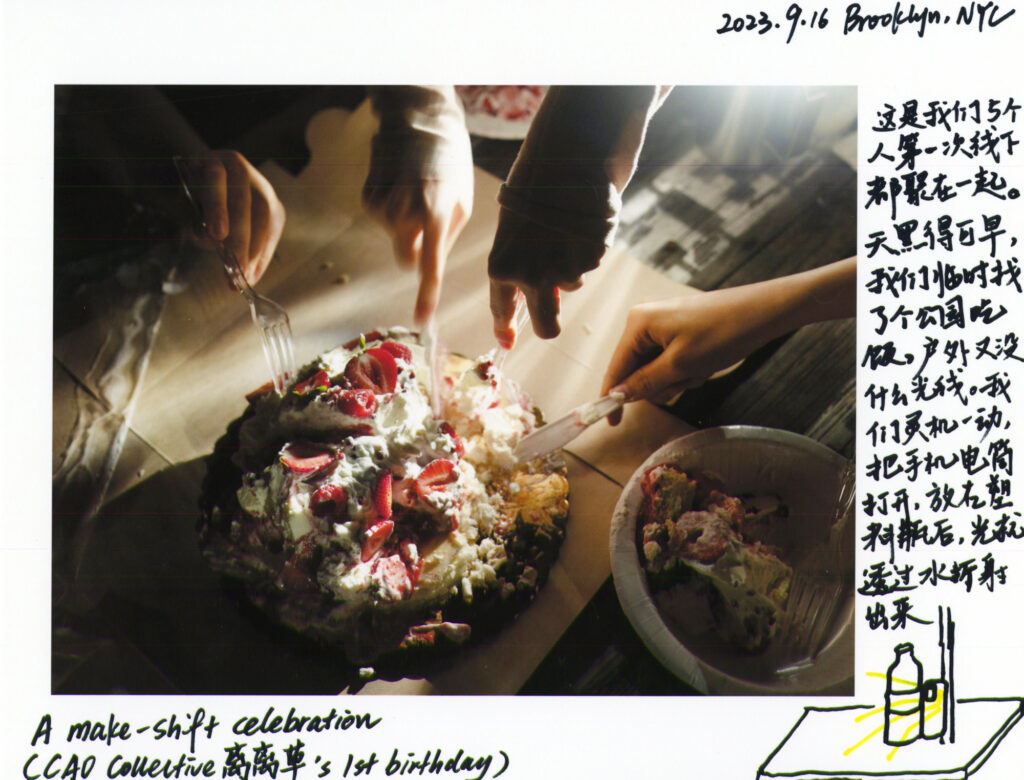

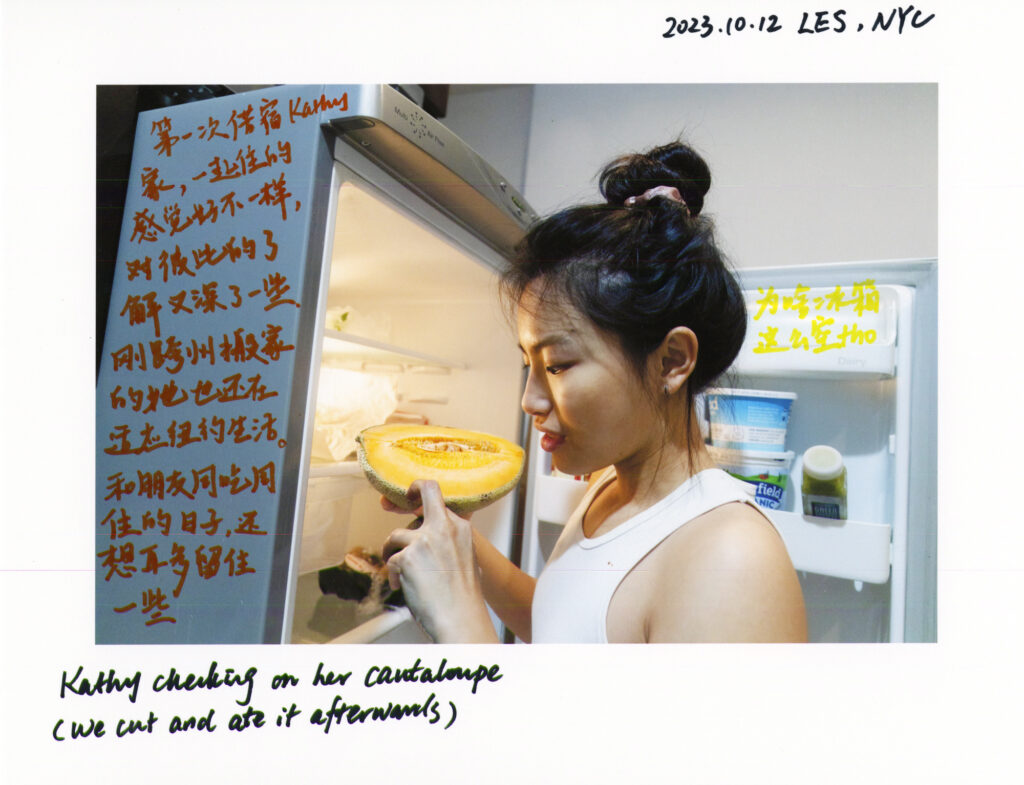

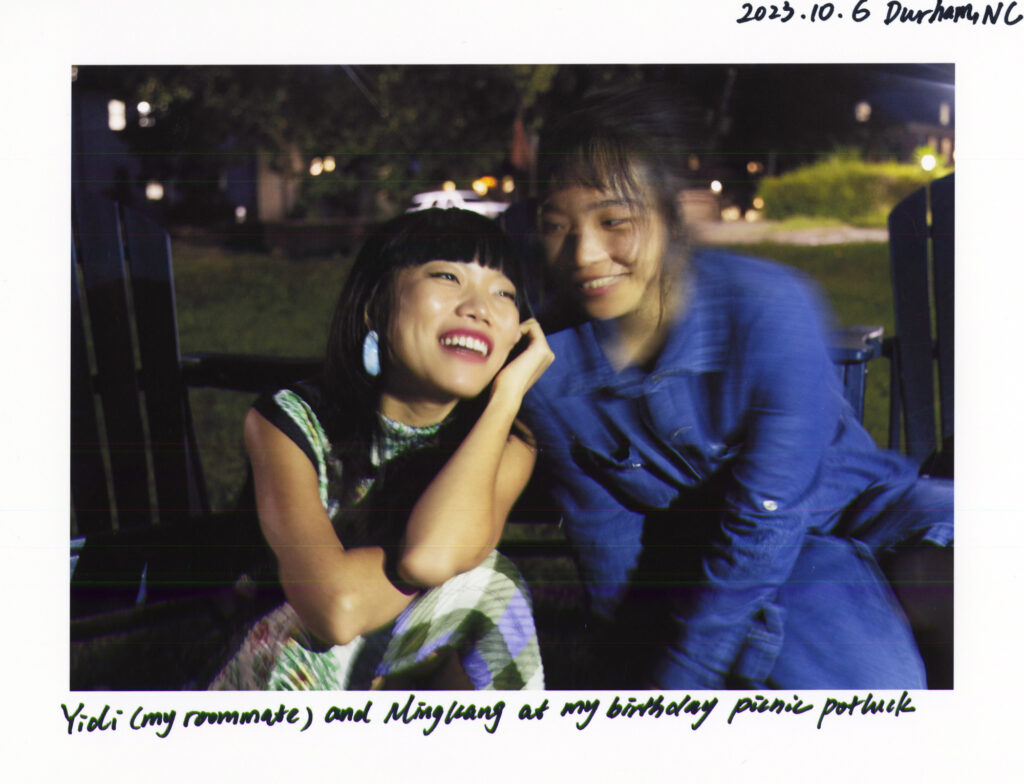

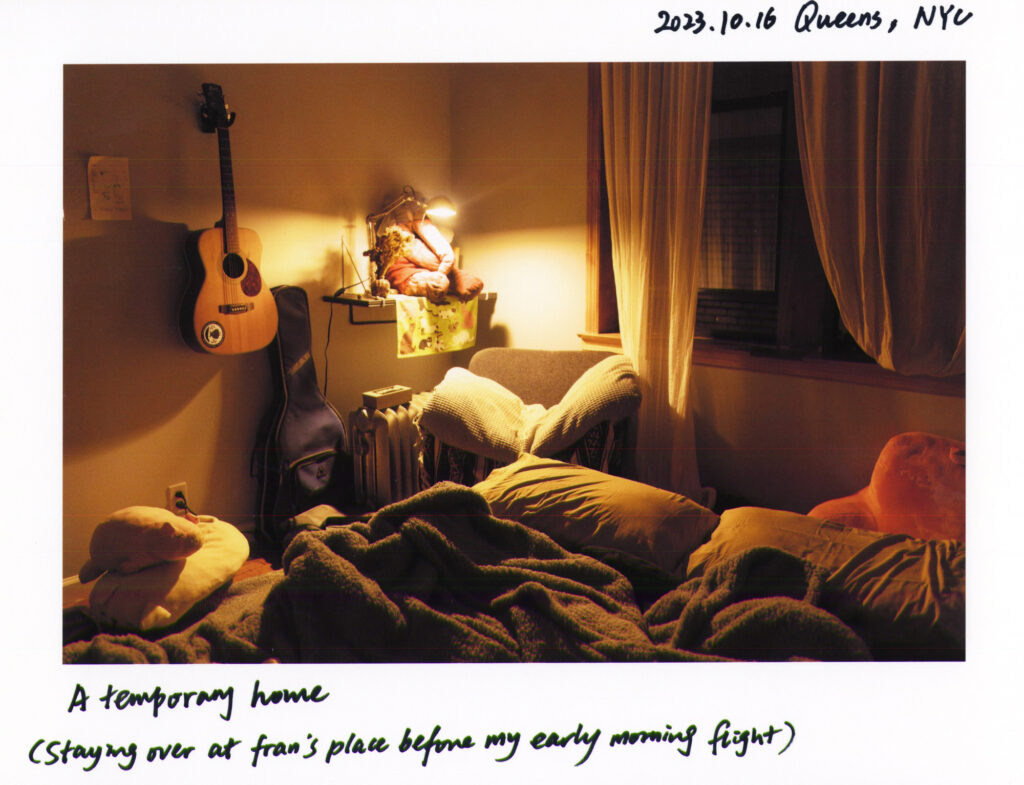

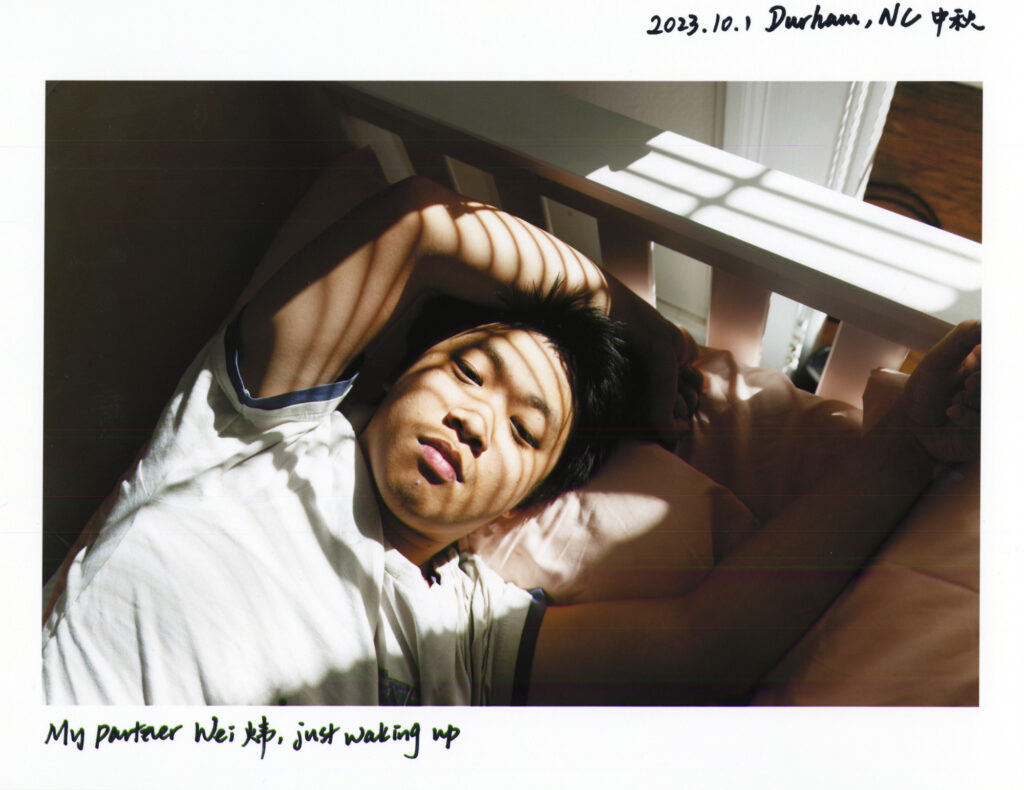

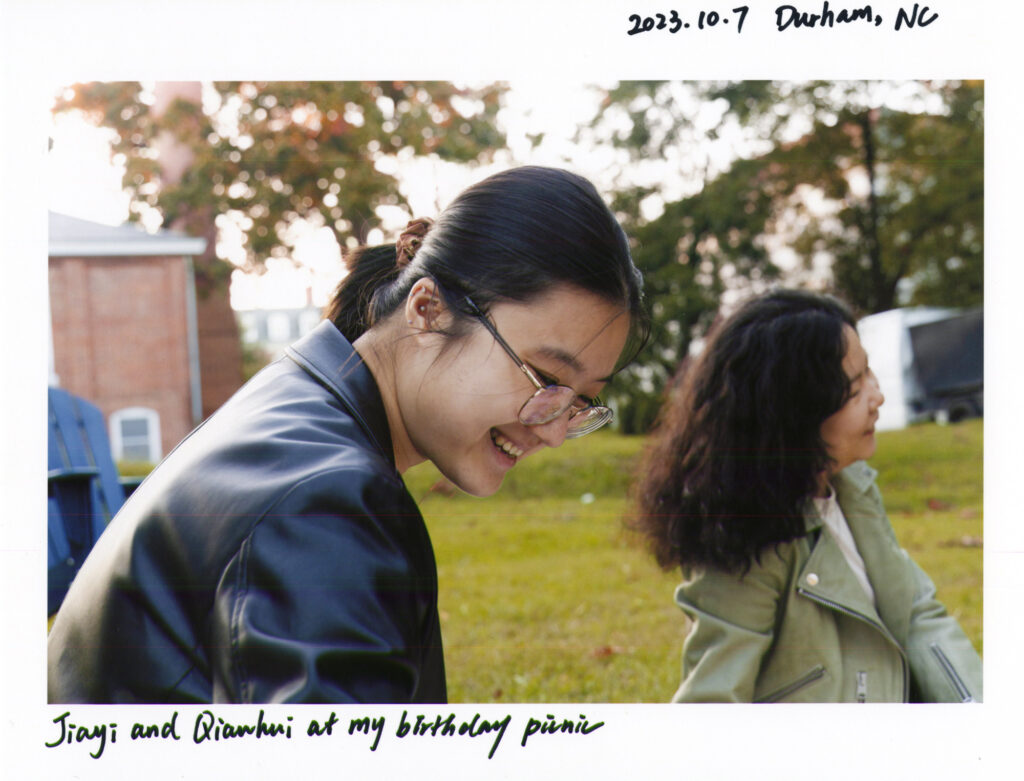

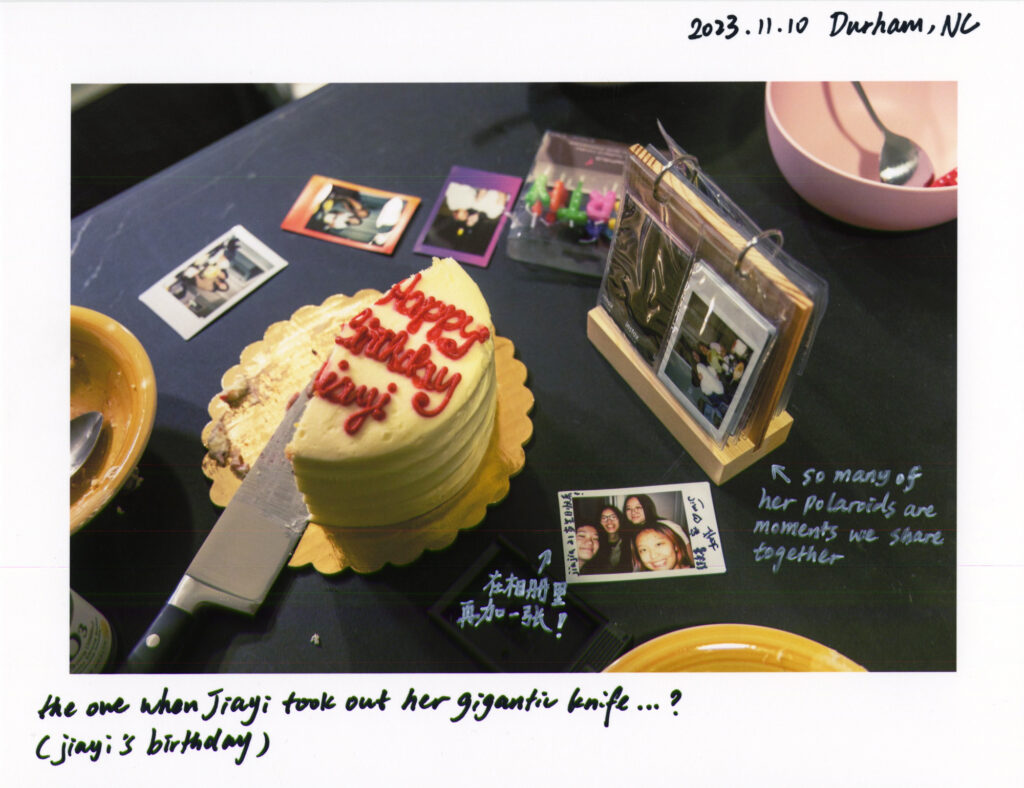

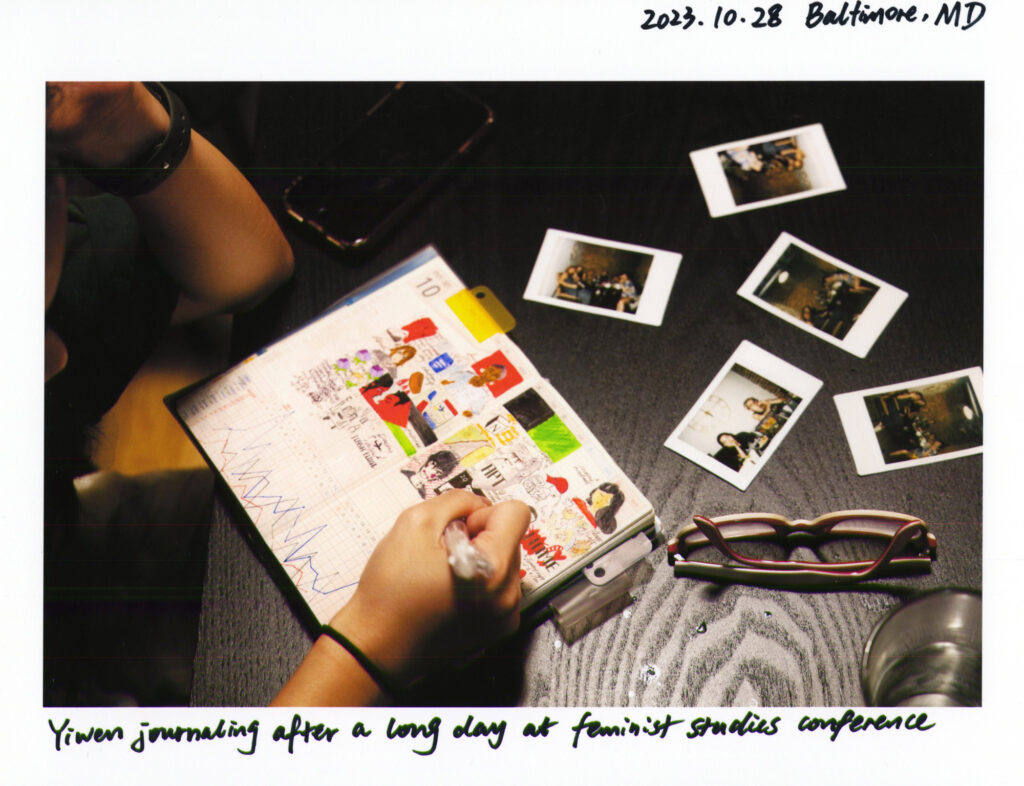

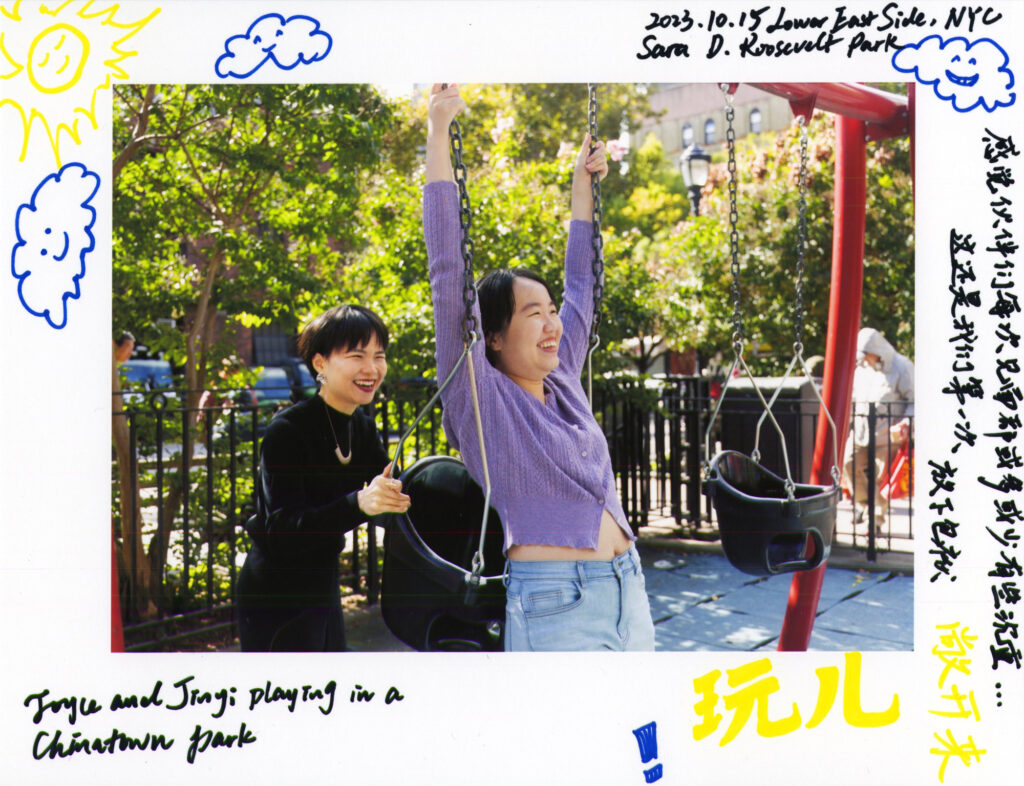

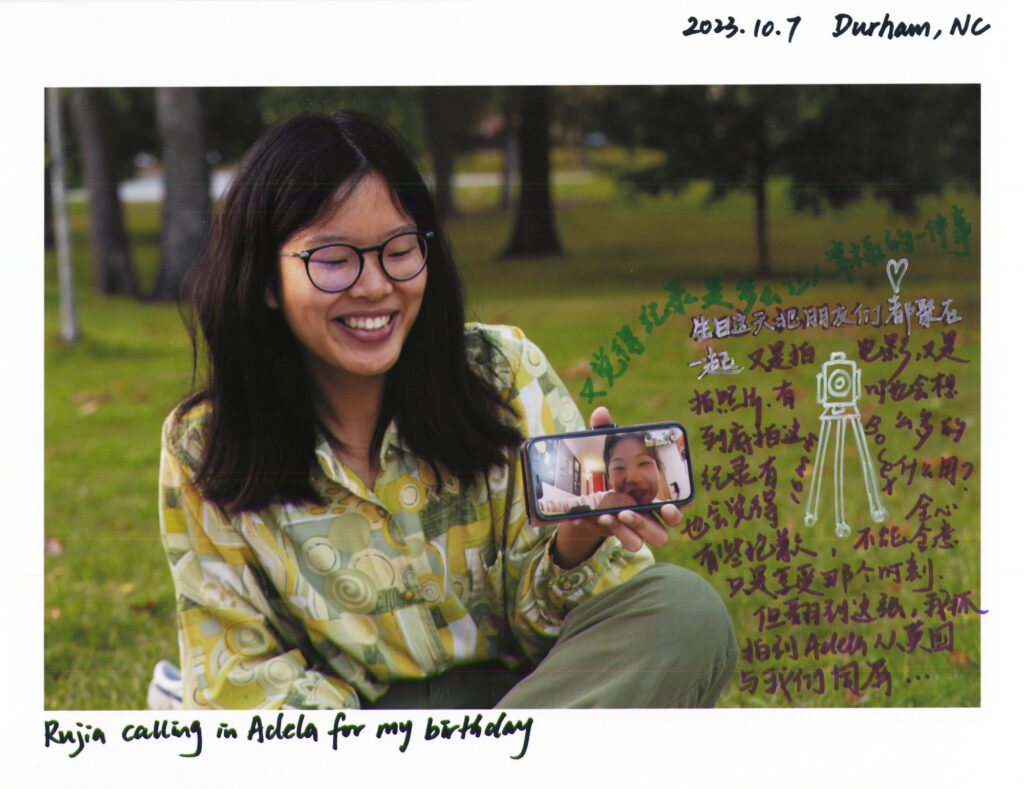

Little did I know what seemed like a fun accident would turn into a relational practice now inseparable from my art and organizing (and even now, Lauren and I still keep forgetting things at each other’s place every time we hang out). For the past two years, I have photographed Chinese queer feminist spaces in Durham, NYC, Irvine, Baltimore, and across various cities in China. The photos I include in this publication were taken in the fall of 2023. Different from what is usually considered social movement photography, which focuses on the “public”, the hypervisible, and acts of protest that are readily registered as political, I want to document the interior, affective lives of a transnational movement built on intentional relations and kinship. These are photos of sharing living spaces, celebrations, grief, rage, play, joy, and rest. Through my photography process, I hope to uncover what Kevin Quashie calls the “sovereignty of the quiet” — the life sustaining rootwork of Chinese queer feminists who insist on seeing each other through our emotions, bodies, and vulnerabilities.

The Chinese title of the series, 一期一会, is a translation from Japanese concept of いちごいちえ ichi-go ichi-e, meaning “for this time only”. With roots in Japanese tea art, it describes the unrepeatability of life and the uniqueness of each encounter that deserves to be treated with care. What registers the people in my photos as “queer” and/or “feminist” if these photos do not show their “difference”? I refuse to treat the affective and everyday experiences of living a queer feminist life as something immediately accessible from images, nor is it an “essence” I can “capture”. Instead, I treat photography as a conversation, a contact improv, and a mutual offering – intimate encounters through which I get to know my friends just a bit more and invite them to witness our own history in the making.

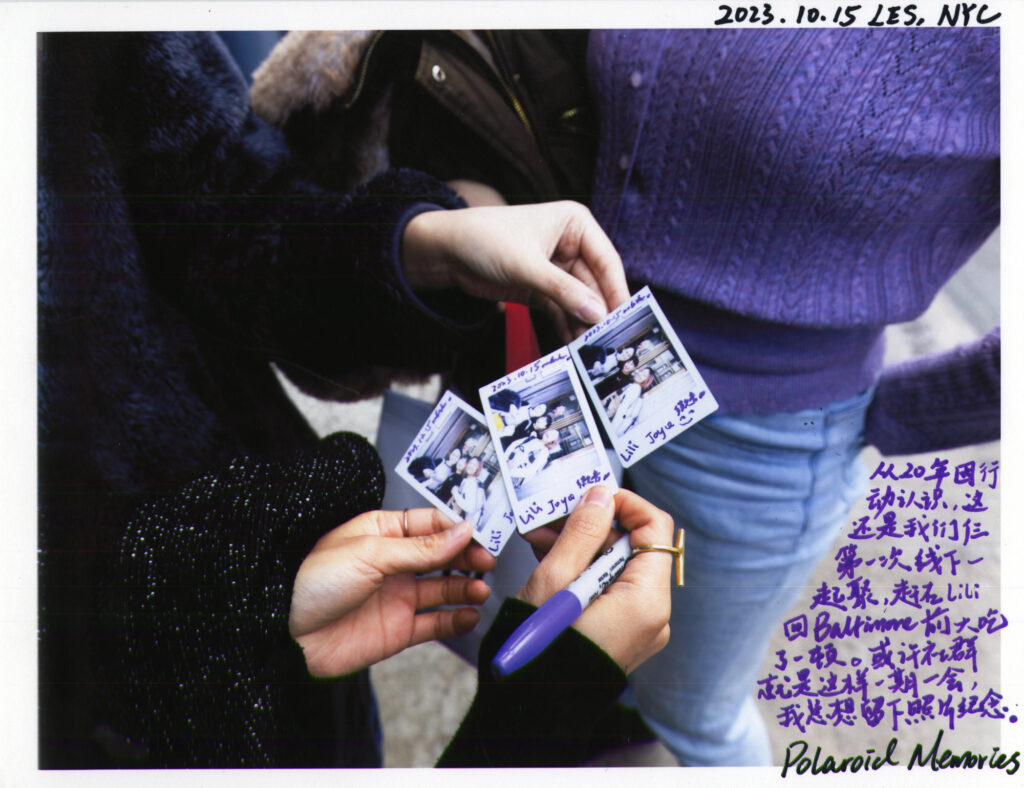

This series is not intended to fit in representational politics that reinforce identity boxes and borders. Instead, I ground the work through my eyes by handwriting my memories, reflections, and dreams on the prints. Inspired by Polaroids I often give people that accompany them across states and oceans, the handwritings bring my body and voice into the images. Weaving the photos, writing, and translation together, I hope to balance contextualizing for the audience to relate to their own experiences while maintaining privacy, opacity and illegibility that I can’t, and shouldn’t, make readily available.

My political awakening as a transnational organizer has gifted me with the sensibilities of memory work, but it also haunts me with a sense of predictive grief that constantly transports me to a future where the current moment no longer exists. Who will remember us if we don’t witness for our own community? When will be the next time we see each other? Having experienced political repression and instability both in China and in the US, every time I entered a community space, I was readily in a state of memory-rescue fearing that these spaces would disappear. Sometimes I felt guilty that I was constantly reminding people of the grief by taking photos, and I am forever grateful for my community’s willingness to share this active grieving process.

Now, a year has passed since I finished the first iteration of this work. Looking back at the photos, many friends have since moved to other places; relationships have ended or transformed; different waves of organizing have ebbed and flowed. My own practice has also evolved—I am learning how to re-center the love and care that provided soil for my grief, while holding compassion for the parts of me that still feel compelled to excavate and rescue. I had considered adding new photos I have taken since then, but I decided to keep them as they were—as a diary exchange with a past version of myself and the unrepeatable encounters I was fortunate enough to witness.

Editor’s note: Below, you can see the 19 images by clicking next or swiping (on mobile).