Birth record translation

No. 38 Treinta y ocho

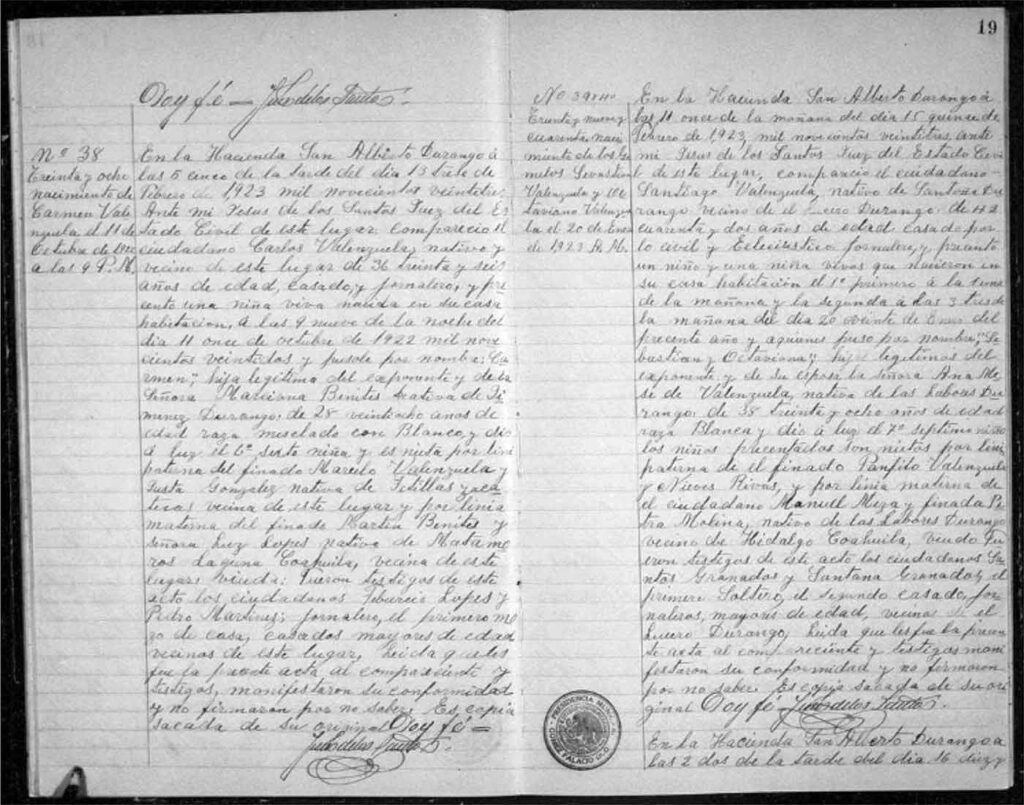

Nacimiento de Carmen Valenzuela el 11 de Octubre de 1922 a las 9 p.m.

En la Hacienda San Alberto Durango a las 5 cinco de la tarde del día 13 trece [sic] de Febrero de 1923 mil novecientos veintitrés ante mi Jesús de los Santos Juez del Estado Civil de este lugar: compareció el ciudadano Carlos Valenzuela, nativo y vecino de este lugar de 36 treinta y seis años de edad, casado, y jornalero, y presentó una niña viva nacida en su casa habitación, a las 9 nueve de la noche del día 11 once de octubre de 1922 mil novecientos veintidós y puesolé por nombre: “Carmen,” hija legitima del exponente y de la Señora Marciana Benites nativa de Jimenez Durango: de 28 veintiocho años de edad raza mezclado con Blanco y dio a luz el 6 sexto niña y es nieta por línea paterna del finado Marcelo Valenzuela y Justa González nativa de Huertillas Zacatecas vecina de este lugar y por línea materna del finado Martin Benites y Señora Luz Lopes nativa de Matamoros Laguna Coahuila, vecina de este lugar: viuda. […]

“At the San Alberto Durango Hacienda at 5:50 p.m. on February 13, 1923, nineteen hundred and twenty-three, before my Jesus de los Santos, Civil State Judge of this place: the citizen Carlos Valenzuela, native and resident, appeared from this place, thirty-six years old, married, a day laborer, and presented a living girl born in his home, at 9:00 p.m. on October 11, 1922, nineteen hundred and twenty-two, and gave her the name: “Carmen,” legitimate daughter of the exponent and of Mrs. Marciana Benites, a native of Jimenez, Durango: 28, twenty-eight years old, mixed race with white and gave birth to her sixth, a girl, and is the paternal granddaughter of the late Marcelo Valenzuela and Justa Gonzalez, a native of Huertillas, Zacatecas, a resident of this place, and by maternal line, granddaughter of the late Martin Benites and Mrs. Luz Lopes, a native of Matamoros Laguna, Coahuila, a resident of this place: widow. […]”

My mother and grandmother were born in ‘the land of the lake,’ or La Comarca de la Laguna, a cradle of fertile land between the Sierra Madre mountain ranges in the northern Mexican desert — la Sierra Madre Occidental to the west, and la Sierra Madre Oriental to the East, two mountain mothers, two guardians that keep the land between them a secret. It is where the Nazas and Aguanaval rivers break their pact with the ocean and empty fresh water into the land, flooding the expanse with wide, glassy lakes — a miracle that enabled life in miles of landlocked desert, and made impossible soil fertile for thousands of years.

The Comarca de la Laguna, derived from the word marca, or border, is itself a borderland in El Norte, that spans the states of Durango, my grandmother Angelica’s birthplace, and Coahuila, where my mother was born, land that also borders the United States. It is also a site of colonial atrocity and indigenous resistance, where New Spain established las haciendas laguneras, a robust cotton industry whose economy was built on the encomienda system, a legal system of forced unpaid labor by subjugated indigenous people who had been dispossessed and detribalized through systematic extermination and unspeakable acts of genocide.

The ‘land of the lake,’ a land with rich soil replenished by the flooding rivers, was an ideal location for these haciendas, and for New Spanish colonists to begin their cotton enterprises for the crown. The frequent seasonal flooding was an ideal form of natural irrigation. In the middle of hostile, arid desert, there was a fertile oasis, virgin and unknown. But cotton is a thirsty crop, for which even the most generous irrigation does not satisfy its root. It exhausts the soil of nutrients; the water it consumes leaves behind a kind of salt, stripping the land to such a degree it becomes a wasteland, requiring abandonment and expansion, usually into forests. Eventually, the land of the lake was covered in cotton, a sea of whiteness over the land.

In fantasy, and poetry, we build the memory of the world through metaphor.

My maternal grandmother Angelica was born on one of these haciendas to farm laborers, and the only way I knew to trace my way back to my foremothers was through Catholic missions, known to keep excellent records.

My mother does not remember her birthplace, Torreon; she was a toddler when they fled. No one ever talks about Jesus, her father, or what happened before they lived in Tampico. All they know is that after he, a 36 year old man married my grandmother, a 14 year old girl, they lost contact after a year, and that the silence became so extreme that her brother, my Tio Joel, had to rescue her and her two babies in the middle of the night three years later, but not before punching him in the face.

So I must begin with the land; it is the only record that remains. And that land between them was once flooded by rivers that became lakes, lakes that due to construction, development, agribusiness, resource extraction, are disappearing, if not already gone. But the land itself is a record; all it does is remember.

We all come from the land, eat from it, drink from it, touch its surfaces. The land is memory made material, and keeps record of every single one of us. It is the first object ever to come into existence; anything that exists after it is because of, and part of, the land. Therefore, its formations and materials are objective and cannot be denied. The land, when interpreted, is so undeniable, it trumps false narratives — ice cores, tree rings, the amount of water left. These facts build a sequence — a story. It is why in school, my favorite kind of rock was the sedimentary rock, the layers of time visible in cross-section, time itself made material, the story it told. I loved when sedimentary rock tilted, twisted, warped, the story of centuries, millennia, ages the land itself told. My mothers’ histories may be forgotten, but the Sierra Madres still exist.

Lacuna (disambiguation)

Lacuna (plural lacunas or lacunae) may refer to:

Related to the meaning “gap”

Lacuna (manuscripts), a gap in a manuscript, inscription, text, painting, or musical work

Great Lacuna, a lacuna of eight leaves in the Codex Regius where there was heroic Old Norse poetry

Lacuna (music), an intentional, extended passage in a musical work during which no notes are played

Scientific lacuna, an area of science that has not been studied but has potential to be studied

Lacuna or accidental gap, in linguistics, a word that does not exist but which would be permitted by the rules of a language

Lacuna, in law, largely overlapping a non liquet (“it is not clear”), a gap (in the law)

In medicine

Lacuna (histology), a small space containing an osteocyte in bone, or chondrocyte in cartilage

Muscular lacuna, a lateral compartment of the thigh

Vascular lacuna, a medial compartment beneath the inguinal ligament

Lacuna magna, the largest of several recesses in the urethra

Other uses

Lacuna model, a tool for unlocking culture differences or missing “gaps” in text

Lacunar amnesia, loss of memory about one specific event

Lacunar stroke, in medicine, the most common type of stroke

Lacuna Coil, an Italian hard rock/metal band

Lacunary function, an analytic function in mathematics

Lacunarity, a mathematical measure of the extent that a pattern contains gaps

Lacunary polynomial, or sparse polynomial

Petrovsky lacuna, in mathematics

Laguna (disambiguation)

Research is a logical process, and evidence must be objective. Responsible research has little to no speculation. Here are the logical facts, arranged into a problem.

Logic problem:

The Rio Grande is the border between the United States and Mexico.

Land O’ Lakes is a butter company that once depicted an illustration of an indigenous woman with a feather in her hair kneeling in front of a lake as its label.

“The company, founded in 1921 by a group of Minnesota dairy farmers, is phasing in a new design ahead of its 100th anniversary. Instead of the depiction of the woman, some products will be labeled ‘Farmer-Owned’ and feature an illustration of a field and lake, or photographs of its farmers, the company announced.” — “Land O’Lakes Removes Native American Woman From Its Products,” New York Times, September 17, 2020.

In 2020, in response to criticism, the depiction of the indigenous woman was removed from the label. Now, only the land, and the lake, remain.

Rivers empty into the ocean, and the end of the river is its mouth.

Rivers empty into the ocean, except the Naza and Aguanaval rivers, which empty into disappearing lakes.

A lake is a lacuna, and a lacuna is also a gap in memory, an absence, a silence.

If the river is a border, and the end is its mouth, where it empties, it speaks.

The Rio Grande empties into the Gulf of Mexico.

Synonyms for gulf.

gulf, noun.

1 our ship sailed east into the gulf. inlet, creek, bight, fjord, estuary, sound, arm of the sea; bay, cove.

2 the ice gave way and a gulf widened slowly. opening, gap, fissure, cleft, split, rift, crevasse, hole, pit, cavity, chasm, abyss, void; ravine, gorge, canyon, gully.

3 there is a growing gulf between the rich and the poor. divergence, contrast, polarity, divide, division, separation, difference, wide area of difference; schism, breach, rift, split, severance, rupture, divorce; chasm, abyss, gap; rare scission.

The Rio Grande speaks into the abyss/void/rupture/divorce/chasm/abyss.

Los Rios Naza and Aguanaval empty into lakes, or lagunas.

The rivers Naza and Aguanaval speak into the land of lakes.

A lacuna is a gap in memory.

“Laguna de Mayrán, Vega de San Pedro, Laguna de Viesca, Laguna del Caimán are long forgotten landscapes, long forgotten names.” — Francisco Valdes-Perezgasga, Orion Magazine

The lakes have disappeared.

At a talk given at the New York Library in 1986, Toni Morrison said, “You know, they straightened out the Mississippi River in places, to make room for houses and livable acreage. Occasionally the river floods these places. ‘Floods’ is the word they use, but in fact it is not flooding; it is remembering. Remembering where it used to be. All water has a perfect memory and is forever trying to get back to where it was. Writers are like that: remembering where we were, that valley we ran through, what the banks were like, the light that was there and the route back to our original place. It is emotional memory — what the nerves and the skin remember as well as how it appeared. And a rush of imagination is our ‘flooding.’”

While I was looking for photos of Torreon, I saw a headline: “Tras 6 años seco, corre agua por el lecho del Río Nazas.” After six years dry, water runs through the River Nazas riverbed, it said. The photo showed a wide, gentle, lazy river, almost like a lake. Also called El Rio de la Laguna, or the river of the lake, it is now contained by the Francisco Zarco dam, constructed in 1968, and has been dry ever since. Once naturally irrigated by seasonal floods, the damming of the rivers has had a devastating effect on the area, forcing the people to use groundwater that is laden with arsenic. The return of the river would replenish the aquifers and solve the arsenic problem, but the dairy industry needs the water to grow alfalfa, the thirstiest crop and single largest user of water, which feeds the cows, which produce the milk. On the United States side, the problem is mirrored — alfalfa consumes 80% of the Colorado River’s water supply, to feed the cows, to produce the milk and meat, and the river is disappearing.

As I read more about it, one fact that should have been obvious stood out — the dry riverbed of the Nazas, the one the water returned to, linked the cities of Torreon, Coahuila and Gomez Palacio, Durango — my mother and grandmother’s birthplaces. After the rains, the dams could not contain the excess, and the floodgates opened. And so the cities were linked again; the land remembered the river’s path, and the river ran and spread like always, into a lake — a river that defies its borders.