In the Union Hall

and in the labor temple: one minute of iron silence.

On a painted wall, our brothers and sisters listened and lifted

their hands, up through years, up through watercolored plaster.

Centuries of workers stood together, heads echoing into distance.

After you died I walked into a room overflowing with your absence.

After you died I stood in a room, heavy in my new voice.

When our Local carried silence for you I didn’t bow my head.

I held your echo at the fresco—strong in my vision—

proud to be your sister in our ancient work.

Our work. What an unbearable weight. What an unbearable delight.

Poem for My Mentor

The Opera House power vault

blows and knocks out the local grid

on our first day of work together.

You haul two gasoline generators

up to the roof, run cable down

the catwalks, power each Leko by hand.

In the air above your crew, you

pull shine out of the dark.

*

From a swaying yellow lift

twenty feet above the stage,

you rig cable picks to batten lines.

A socket wrench nests

in your palm like a second thumb.

Worklight focuses a glory

around the black hairs on

your head, your stubborn gut.

I wonder if anyone has told you this.

I wonder if you know.

*

When I hear that you have cancer

my hands go peach-fuzz numb.

I bore my fingernails

into my palm,

hands no longer mine.

I think maybe, maybe gloves

will help, a solid rub, a puff

of breath, a stretch.

Finding no

success, I turn

to what I learned

from the cold woman

in the public john:

torque the red

faucet left,

forge the tendons

warm again.

*

One not-yet-spring evening

we meet for a quick meal.

I eat as slowly as I can

but my plate still fills with crumbs.

You talk about letters you’ve written

to your young son.

You talk about dying

like it’s part of the job,

like this city wouldn’t disintegrate

without you.

*

Scenic structures crimp

and fold, worth nothing.

Welds, all bad, lumped and bulbed,

should be slick and blue.

This color is how you know

the join will hold you say.

You take my useless hands,

pour in a wealth of sparks.

*

Because you are alive

I will not write your elegy.

I will not write your elegy

because you are alive.

■

Typical Duties: Master Electrician

Work on your feet

for 16-hour days.

Clock minutes to fill the room, carry

copper under-tongue.

Calculate amperage. Call

numbers across auditorium air.

Embed metal swarf

in your thumbprint arch.

Smell spent lumber on a saw—sweet char

as the saw goes dull.

Work hungry

& fatigued. Work dirty.

Exhaust the soft oils

of your fingertips on steel.

Electrician’s Litany

the rig manipulates a million

watts of power | sometimes we light

only a single lamp | mimic

the setting sun or rising

one | or the limit of dark

over an unseen body

of water | the first potentiometers

were tanks of saline | copper

plates | frequent mortal

accidents | our modern offerings

are more acute | a crushed

foot | a knuckle cut | in place

of prayer | we rest

our knees | into concrete

and sink | our bodies

we ruin

Stagehand’s Offering

I spent three days with a relic

sour in my ring-fingertip.

You stayed out sick when chemo

augered you.

We worked to make the play in spite of this.

Seeing our offering of story and light

God was benevolent.

God handed you a crescent wrench and said

Not Yet

The Work Is Not Yet Finished

Listen. Even the ancients built theatres

as temples to their gods.

I’ve learned to praise ten thousand knots

tied in tired palms.

Our bodies’ aches are wrapped into this place

as wire twined on wire strands.

I keep the voice of the Almighty

on pieces of tape

with circuit numbers written in your hand.

You will leave us.

These knots will hold your ghost here.

Outside it’s raining, spring-crazy.

Look. Someone’s painted flowers

on streetlight boxes

all across the city.

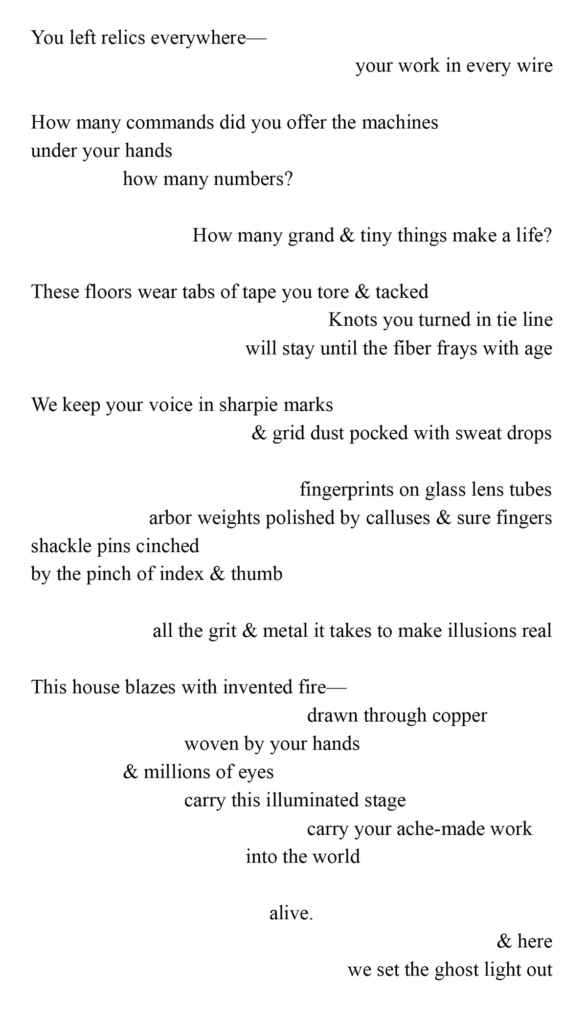

The Ghost Light

in memory of Andrew Lon Willhelm