PACIFIC HOMING

老家 are the characters: old and home. Which is better translated as one’s “ancestral home”. The 老家 is the place and community where your lineage can be traced. It denotes your place of origin, a native land.

太平 are the characters: grand and peace. 太平 is the name of my ancestral home. This is where my paternal grandfather is from and where my lineage has been traced for over twenty generations in our 家谱 (family book of genealogy).

I grew up at the foot of the mountains where my 老家 is, so I have visited often with my grandparents. Although the migration of peoples is inherent in the history of the world, the Han Chinese people have been rooted for thousands of years within their lands. This is the case for my paternal and maternal lineage, making my parents’ departure the first instance of intercontinental migration in centuries.

Reunification I

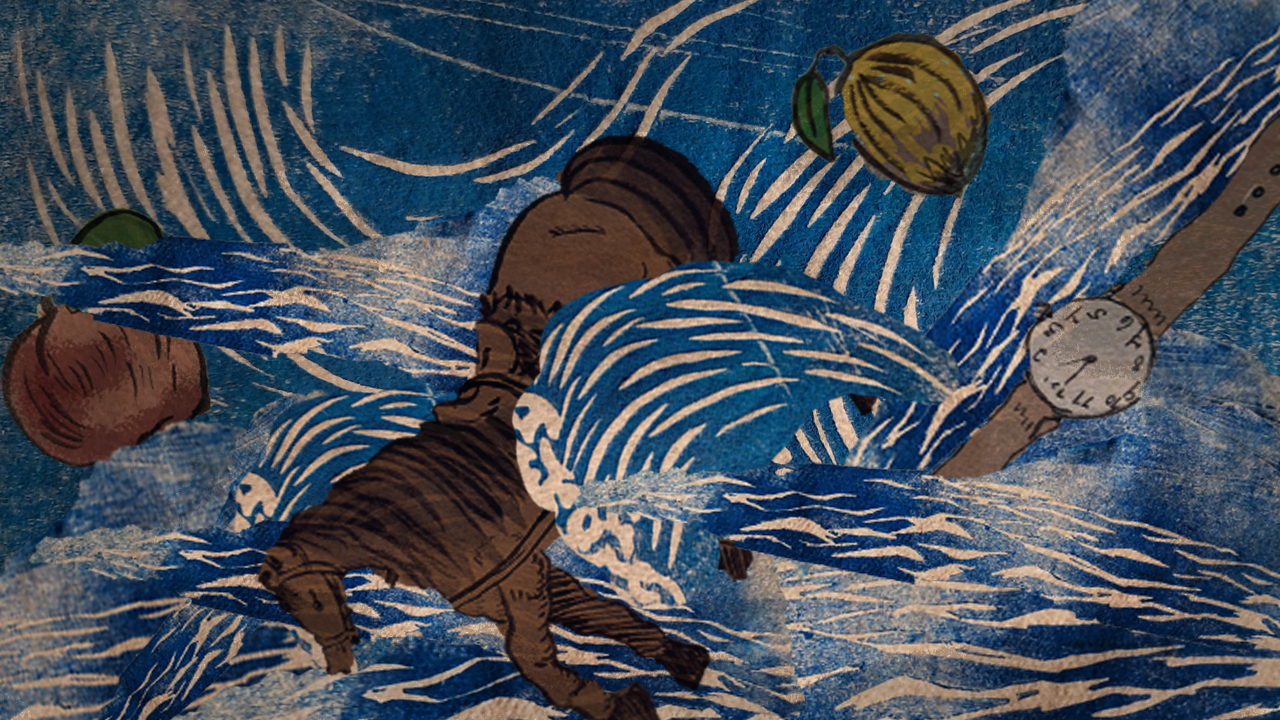

The day I reunited with my parents, I woke up in my grandmother’s lap with salt in my mouth. Through the haze of yesterday, her scrunched-up face slowly came into focus. The Earth rumbled beneath me as her tears streamed into me.

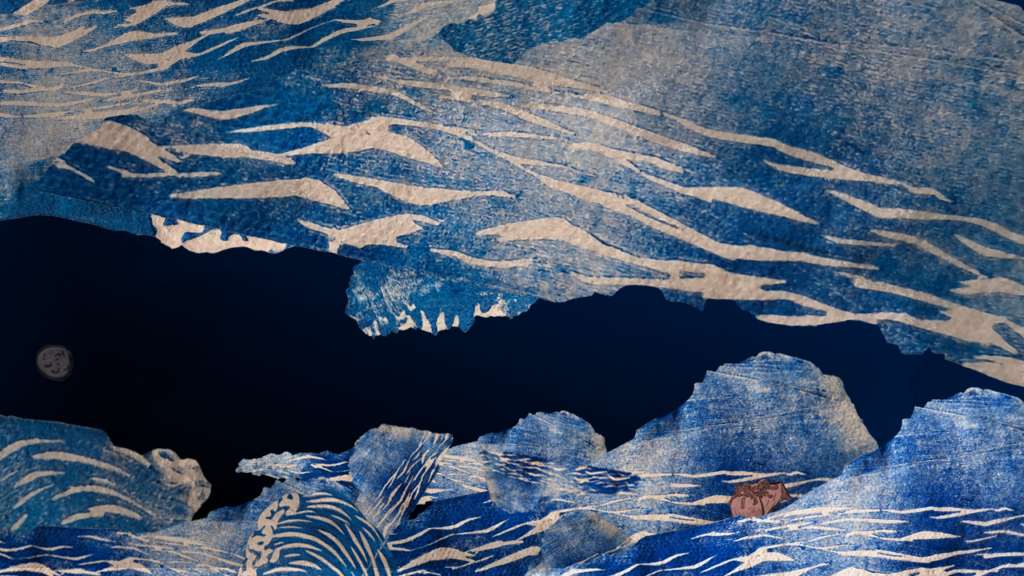

Tectonic plates moving apart, form a rift at the bottom of the ocean floor.

Like an inheritance, my grandma’s grief and pain of the imminent separation presented itself to me. This would be my last day in my hometown living a life I had never questioned would end. This would be the first day in a life with my parents, who were strangers with only a nominal title of governance over me at that point.

A celestial body pulled out of orbit, fearing an ejection from its parent system.

As I drifted across worlds and borders with my parents, I often found myself lingering in the valley the rift had left behind. I tended its scars and filled its chasm with that same salty taste. When the land I stood on no longer meant home, home became foreign along with me. Unable to process my separation and this most ambiguous loss, home became a thing of the past and its comfort felt like a sacred myth.

There’s a saying in Chinese that explains traveler’s sickness: 水土不服. It suggests the soil and water that cultivate the local food are foreign to your system, which will cause you to reject it. Or perhaps it’s the soil and water that are rejecting the traveler. Whichever way it is interpreted, traveler’s sickness is known to befall all visitors who come to my hometown. International and domestic visitors alike, my hometown is unforgiving to anyone who was not nurtured and tended to by our land.

In this way, my homeland speaks as my gut microbiome witnesses.

Claiming me in that unceremonious way that I claim home.

Pacific Homing

I have always yearned for a home that could transcend geography. A home that I could carry with me, that I could hold onto. Something stable in my instability.

When I stepped into the Pacific Ocean, my yearning was received with a reply. I felt the shores of home rush me from across the ocean.

I saw the rift that had formed twelve years ago, and this time I was standing knee-deep in its salty reserves.

I took a big breath of the sea breeze and exhaled it into a cry.

For the first time, I let myself be awed by its beauty and marvel at its depth.

Interestingly, or perhaps serendipitously:

My hometown, 太平, shares the same two characters used for the Pacific, 太平, in Mandarin Chinese

Of Balconies and Sunday Blues

Sunday afternoon tea with 奶奶, hand shadow puppet shows, homemade rice wine and drying meats, and cakeboxes filled with worms for fishing.

Every boom of the Spring Festival fireworks.

Forever unreachable after one Summer morning of goodbyes.

I would dream of the balcony. Finding myself there,

surrounded by those tinted windows casting a hue so radiant that

everything became the warm blue of a Sunday afternoon.

With no one in sight, a closeness creeps towards me.

Then the burgeoning immediacy of my mother’s presence.

An impression, the glimpse of a specter in the light.

Now it’s all I have to show for my childhood home.

An impression, the glimpse of a specter in the light.

A world away. 7,500 miles away. Aways away.

I am to embody everyone, the bridge that tears away at the daunting distance.

Every glance at the moon, every sip of rice wine, every misty morning, every cup of 毛尖 green tea. Every dream lulled by rainfall.

Closeness must become of me.

For a moment, it is as if I were only ever that passing specter drifting on the balcony of my childhood home.

They Came in The Summer

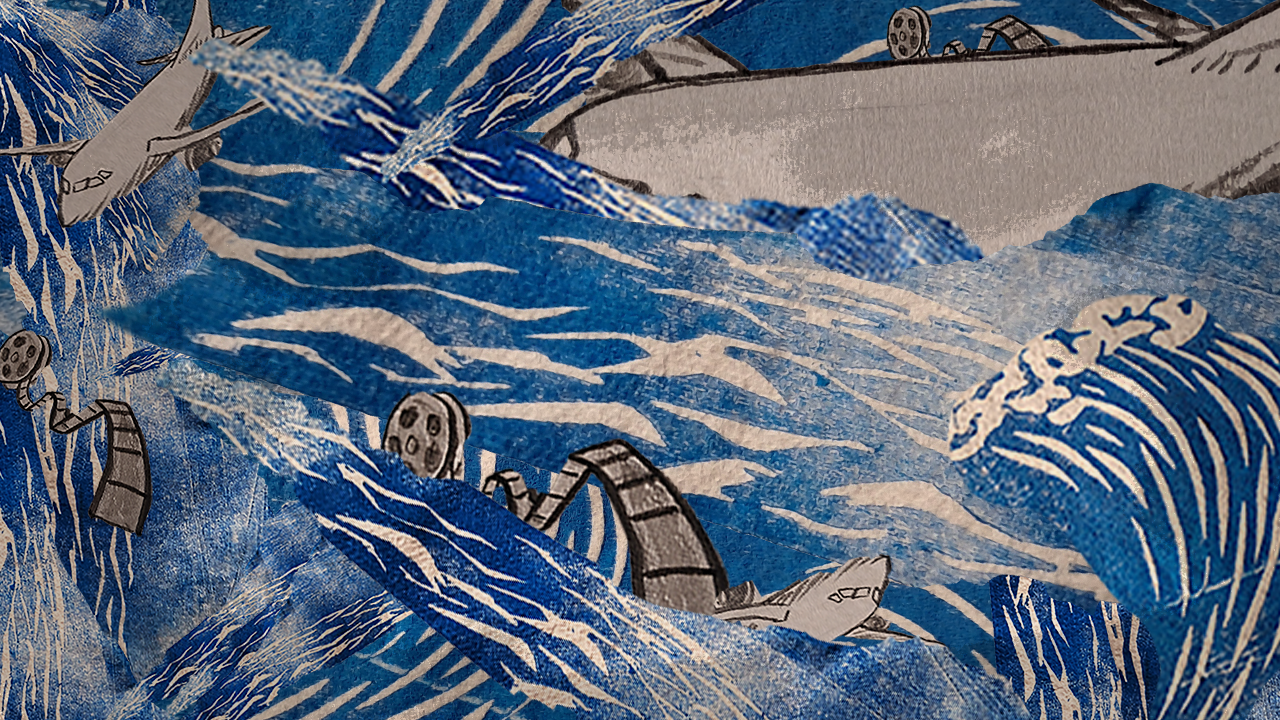

July, 1937 promised harvest to the rising sun

scorched Earth and last times.

in the soot of our house

I saw my father for a last time.

in the shrines of our temple

I prayed for myself for a last time.

in the pharmacies of our town

moshi moshi! yaku? 薬?1

September, 1945 – we bid them a proper autumnal goodbye.

One last time,

home still stood.

the land. the rivers. the seasons.

and me

Once, my grandpa started speaking to me in Japanese, foggy from dementia. Repeating this line over and over again. My grandmother let me know that he was not talking to me; he thought he was talking to the Japanese soldiers. So this was him repeating the Japanese he retained from the war when he was a child. I learned quickly that he only knew how to ask for medicine.

Reunification II

“Eventually, come home.”

奶奶 warns me like a verbal talisman.

Homing is to each generation a practice and a path.

In my family, home is not passed on but arrived to.

For my grandfather,

orphaned and raised by the land,

home is found in the soil.

For my grandmother,

displaced from her ancestral home at birth by the Japanese army,

home is found in the family you build.

For my parents,

serial migrants who had to cross the world again and again,

home is found in the imagined communities of nationality and religion.

For me,

raised in migration,

home is a journey of mine.

It is my turn to define

what is home

where is home

who is home

and finally

how we ought to come home.

Goodbye, Welcome.

When my friend drove me to the airport for my flight to China, he sent me off with a ceremonious song about going home. Soaking in the beautiful LA sunset, I let myself get lost in the melody.

“Goodbye L.A. I’ll see you soon. Goodbye L.A. I’m going home, for now.”

I suddenly realized, the alarmingly obvious: I’m going home. for now. only now. Finally now.

In Chinese, when we return to the homeland, we use 回国 (return to country). That had become my narrative for this trip, so much so that I neglected to acknowledge the trip as coming home.

15 years of away, I had finally found a home on foreign grounds.

15 years of homing somehow made my homecoming unapparent.

“Safe trip home,” my friend said while embracing me outside the airport.

From the language I said to the aches in my body: “I’m going home.”

My grandma received me with tears in her eyes and a slap on my shoulder:

“哎呀,琪琪! 终于回家啦!” // “Aiya, Qiqi! You’re finally home!”

Her words echoed as we embraced.

Home is leaving with a goodbye and returning to a welcome.