My parents gave up a comfortable life in China so that their children could have better opportunities. When they came to America, like all immigrants, they struggled. First, they had my sister, and four years later they had me. I was sent back to China between the ages of two and four. I stayed with my aunt and uncle because my parents couldn’t afford to care for both children at the same time. Growing up, my mom fed me stories as though this was a vacation, whether out of guilt, survival, or ignorance. She shaped my story before I even had time to process or react to the experience.

When I started grade school in America, I would share my story with my friends because it felt like a cool fun fact. Something interesting to say to fill the silences. Somewhere between grade school and college, this experience morphed into something embarrassing at best and shameful at worst. I realized no one else I’ve ever met could relate to my story. I forgot about it entirely until these past two years when I began to explore my complicated relationship with my mom through my artwork and therapy.

In 2016 my friend sent me this compelling essay on NPR written by Beth Fertig called “For ‘Satellite Babies,’ Separation Can Take Its Toll.” It was about children born in the U.S. and raised in China. My entire life I thought I was the only person who went through this specific relational trauma.

During the first few years, babies are developing an attachment to their parents. When this is disrupted either by neglect, abuse, or circumstance, it can have long-term effects on their internal working model. Children who experienced relational trauma can develop avoidant or anxious attachment styles instead of secure attachment styles. The sparse memories I have of my time in China were negative. As a child, you are unable to process information separate from yourself. Everything that happens to you, you relate back to yourself. This thing happened. I must have done something wrong. I must be bad.

When you learn shame as a child, and that shame is reinforced early on, it becomes a habit, and that habit becomes ingrained into your internal working model. As an adult, I can logically understand why my parents made that difficult decision, but the habits and the feelings of unworthiness do not have an on and off switch. It still affects me.

One of the most poignant memories I have, and it’s also the memory my mom used to recount continually, was when we were first reunited in China: “When I flew from America to pick you up in China, I rushed from the airport to your boarding school. When I came to your classroom, you were handing out bread to the other kids. Then I called your name, and you looked at me for a few seconds, but continued handing out bread. Finally, I said, ‘Bianca, it’s me, Mom.’ From that moment on, you never left my side until we went back home to America.”

Back then, there was no FaceTime. I would only be able to talk on the phone with my parents. For two years, I never saw them. The fact that I didn’t remember what my mom looked like makes me feel powerless for the four-year-old me.

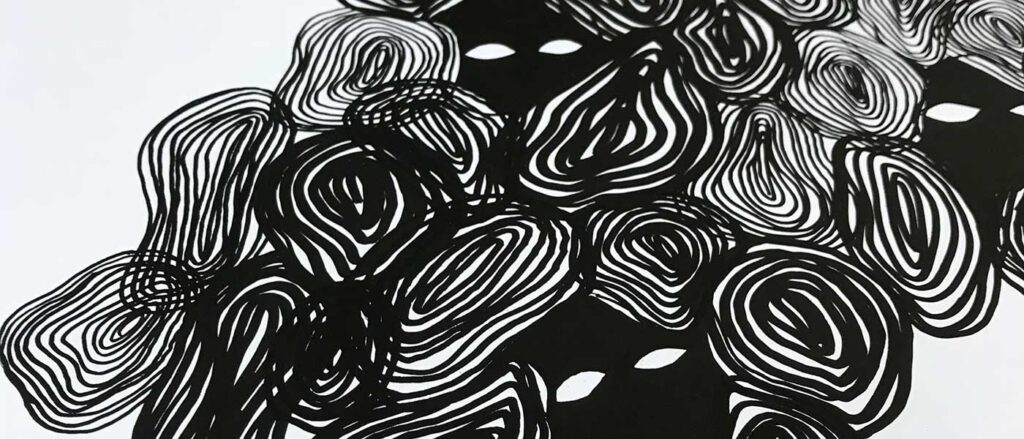

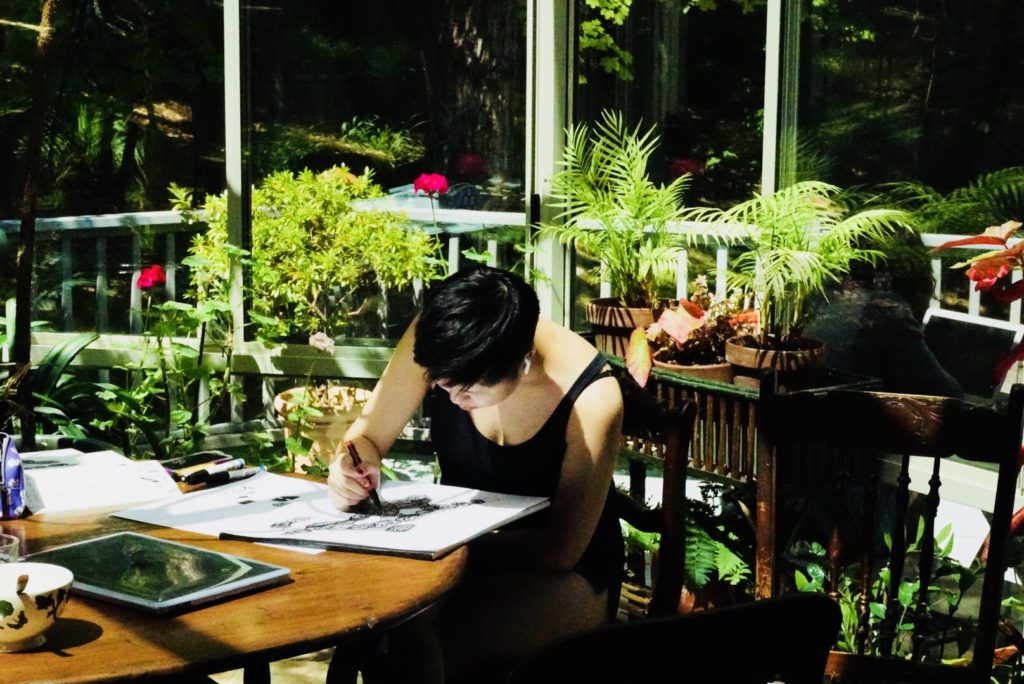

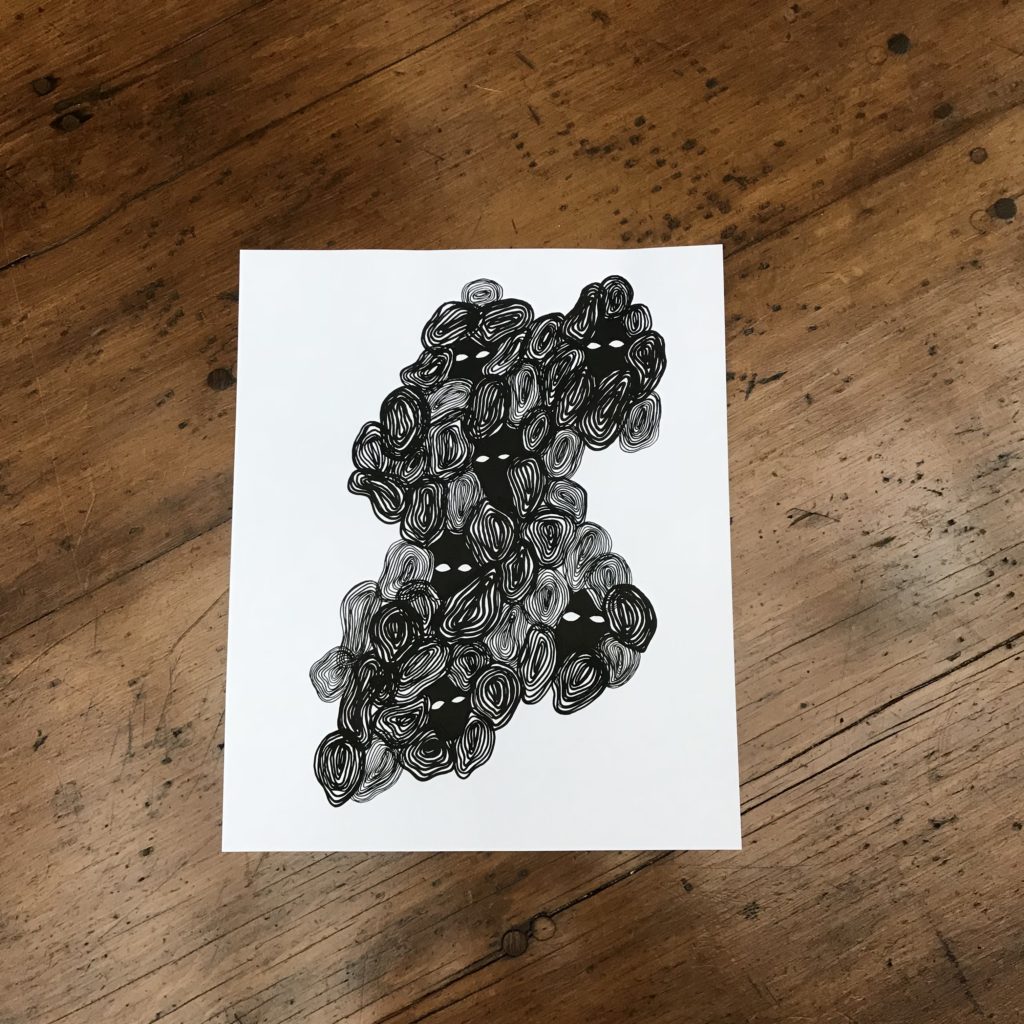

This story asks more questions than it answers. I’m illustrating this experience to bring awareness about the realities of the Satellite Baby experience. It’s not a story of blame or victimhood. It’s a story to shed light about a surprisingly common experience many Chinese Americans go through, but that is never openly discussed. I hope for this work of art to be a conversation starter. I wonder about children who had similar experiences as me, and I wonder about children who just grew up separated from their parents due to circumstance.

How does this affect them into adulthood?

- Born In The U.S., Raised In China: ‘Satellite Babies’ Have A Hard Time Coming Home

- For ‘Satellite Babies,’ Separation Can Take Its Toll

- Attachment Theory and the Developmental Consequences of Relational Trauma

- From the US to China and back again by age six. Why ‘satellite babies’ struggle

- The Family Development Project