I had finally begun to build a home of my own. Unsettled and confused after college, I moved to Monterey, a coastal town in California, where I was amongst friends and working as a preschool teacher. Things seemed to be falling into place for me in this sleepy, picturesque town, and I was feeling stable and confident with my choices. But three months after my arrival, as I was getting ready to attend an event, the phone rang; it was my father calling to tell me that my younger brother had died of a drug overdose. He had been struggling for years, but we had not realized how truly desperate his issues had gotten. Crouched on my bedroom floor, reeling from the phone call, I hyperventilated and screamed into the hollow air, destroyed.

I called a friend, not knowing what to do with myself. She volunteered to drive me four hours to my father’s house, knowing that I was not able to do so on my own. My father opened the door, his face flushed and eyes glossy. “My sweetheart.” Our friends sat in the living room, on a sofa that had been moved so the gurney could carry the body out. My grandmother wailed when my father called to tell her the news — a guttural, aching noise. When he handed me the phone, she whispered, “We’ll get through. You’ll just have to be our rose.”

In the following days, my father and I tried to pacify ourselves with self-destructive behavior, drinking tall glasses of red wine at noon, lingering over childhood photos, going through his belongings. A belated birthday card I had sent him days prior arrived, and his friends began calling, asking why he wasn’t answering his phone. I took shots of vodka in the middle of the night, sedation the only way to stop me from shaking incessantly. Eating was a mechanical task, bathing was arbitrary, and the television was a meaningless blur of motion I stared at so I wouldn’t have to speak. I indulged in senseless denial, hearing my brother’s footsteps on the creaky porch as I waited for the door to open.

Our childhood was so lovely. I was always the quiet one but he was comically precocious, all saucer eyes and cherub hair. When we were children, he would usually get more attention and affection but I didn’t mind because I gave him mine too. Sarajevo, the capital city of Bosnia where we lived, was alluring and rich with culture. Nestled at the bottom of a mountainous basin, it housed Serbs, Croatians, and Bosnians who were Muslim, Catholic, and Christian, among other religions and ethnicities. My father was a journalist and my mother a homemaker. They had met at a campground that my grandmother ran in the lush tourist town of Orebic, Croatia, where we spent our summers. He was a Bosnian with a Serbian background and she a Croatian, facts completely irrelevant in our social circles, where ethnicities mixed freely.

Tragedy struck when my mother succumbed to cancer. My brother and I, only 3 and 7 at the time, did not understand the permanence of her passing and never had the time to process it since a genocidal war erupted only months later. At the time, Yugoslavia was a hotly contested territory because it lay in the middle of the European continent. It had changed hands many times and had been the property of the Ottoman and Austro Hungarian Empires; in 1918 it became a country that consisted of seven separate territories. In the early 90s, the Serbian Army, at the insistence of President Slobodan Milosevic, began a campaign to reclaim the parts of Bosnia they believed belonged to them. They wanted to cleanse the country of Bosnian Muslims, who, in their eyes, were inferior and undeserving. Sarajevo was seized, the residents hunted like animals by soldiers who hid in the woods surrounding the city. The city, beautiful for its diversity, was demolished as its citizens began to flee and perish. Neighbors turned on one another; those who had once shared recipes and advice were now spilling each other’s blood, having abandoned their morals and humanity.

My younger brother and I fled during the first days of the war and lived with our grandmother in Serbia. We had little money and supplemented our meals with UNICEF care packages. Our new friends’ parents pitied us; they gave us mournful looks when passing us in the halls and brought us chocolates after school. Though we feared the worst would happen to our father, we were happy with the little we had and fortunate to have an adult to care for us.

Even under such dire conditions, my brother continued to be the innocent troublemaker he always was. Every week, he would defy grandmother and she would chase him around the house with a belt while he outran her, cackling. She would scream at us when we played tag in the house and tipped over the giant bags of flour we got from relief agencies. He was my lifeline and my partner. I held his hand as I walked him to kindergarten every morning and taught him to look both ways when crossing the street. We would go watch American movies with our cousins and I would read him the subtitles since he didn’t know how to yet. In the woods, we went ladybug hunting and looked for mushrooms with our aunts when food became scarce, resourceful foraging that was fun due to our childhood naiveté. Our father joined us in Serbia after more than two years of being trapped in the war. Of mixed blood and with no prospects, we knew our future was in the U.S., where we would not be persecuted.

We arrived to our house in our tiny new town in America four months later, a sizeable home owned by an older relative who let us live there for free. It was empty and echoed and we had nothing to fill it with other than suitcases full of photos and clothes. The world outside was full of uncertainty but bustled with possibility. My brother and I found comfort in each other yet again, as we had nothing and nobody else.

We couldn’t wait to be like the other kids at school. For the first few weeks, muffled intercom voices would summon me to go comfort my brother, who could not stop crying. My cheeks would redden with embarrassment, but when I saw him, I would also be happy because he was the only one who really knew me there, and he was just as scared as I was. We resented the other kids for not understanding us but ached to be like them, to wear Nike socks, eat granola bars at snack time, and have parents who could explain the world around us, rather than having to figure it out together.

It took some time but we assimilated fairly quickly; the language came easily to us and we began to copy our classmates, the way they dressed and the games they played. I helped my brother with his homework and attended Mother’s Day brunch with his classmates since she wasn’t there. These adults all pitied us too, I knew, but we were OK. My eternally selfless father had begun working in construction and attending ESL classes; he did all he could bear so we could live comfortably. Our weekly allowance was a quarter and we would gleefully argue over which vending machine our treat would come from. I helped both my father and my brother with their homework since I spoke English fairly well, and they knew very little. We began to call the U.S. our home and slowly assimilated to the culture; we were becoming as American as our friends.

Four grades apart, my brother and I began to grow more distant as I moved on to high school. We had different groups of friends and interests. I didn’t pay it much mind; it happened organically and gradually as we both become self-centered teenagers. He was navigating puberty and I was trying to figure out life plans. But my big love for him persisted even though we spent less time together. He was the only one woven into my shifting world from the beginning.

At my father’s urging, we went back to Bosnia after we officially got our American citizenship, seven years after we had left. I revisited Sarajevo’s cobblestone streets, the swarms of pigeons gliding through Old Town, the prayer calls crackling through the morning air, but they seemed foreign somehow. The custom of taking one’s shoes off felt unnecessary now, and the fact that many people smoked indoors disgusted my brother and me. Sarajevo stood where it always had, but it was now riddled with bullet holes, made gray by unspeakable events. My friends looked older but the same. They were now in college, like I was about to be. They were living their lives in nearly the same circles, smaller now because of casualties and those who had fled. They had lived through inhuman events but they were resilient, strong, bright, and kind. I was reticent to experience and see our past but my brother submerged himself in the culture, peppering his speech with newly learned idioms and persuading our aunt to make him his favorite childhood meals. She could not resist the charming boy when he was small and she couldn’t now; we were soon eating dessert every night. Despite the pleasures of reminiscing, however, every time I returned to the States, I felt an easy relief. It was simpler there. We didn’t have to talk about the war, think about betrayals, or hear stories of human ugliness.

When we returned from our trip, I began college and my brother started high school. We kept in touch, but as we adjusted to new circumstances, our talks became brief and less frequent. I sensed he was becoming distant and questioned his choice of friends. At times, I would become angry when we spoke as he would ask me the same questions each time; I now know it was a side effect of intoxication, rather than apathy. He had begun abusing prescription medication without our family’s knowledge, hiding it from us as his habit began to consume him. In later years, we discovered his problem and tried to help but couldn’t, never fully understanding the extent of the addiction, that it had become rooted inside him. I thought this was a phase that would soon pass and couldn’t wait to get my friend back. It would be soon, I thought, it could happen anytime. But despite our eroding relationship, periodic summer visits back home slid us back into our childhood; we binged on candy, watched poorly dubbed Italian soap operas, and spent evenings with my grandmother in the campground, watching the moon reflect on the inky seawater. Through all the challenges, I had no doubt he would be OK; we would be OK. We always were.

There was one year when he went to visit home, and I couldn’t make it because of work. When we spoke on the phone, he sounded lucid and sharp. He talked about my grandmother and how he was cutting down the incessant weeds in the campground, and about my uncle and his eccentricities. I forced him to list all of the homeland foods he had been eating, green with envy. Weeks later, he called me from Sarajevo elated; the authorities had caught Slobodan Milosevic, a politician who was accused of war crimes. A small retribution for horrors that could never be undone. The city was in an uproar; people wept and cheered, full of happiness and sorrow. I yearned to be there, holding his hand and crying with the city. When he returned to the U.S., he called me to tell me how unhappy he was. He had been fired from a string of jobs he cared little about before he left and was now having trouble finding employment again. His friends were aimless and obnoxious, they were dragging him down, and he wanted to move, to start culinary school down south. It was time for a change, I thought, and so I told him to move forward with his plans. Excited to watch his new adventure unravel, I said I love you and I hung up for the last time.

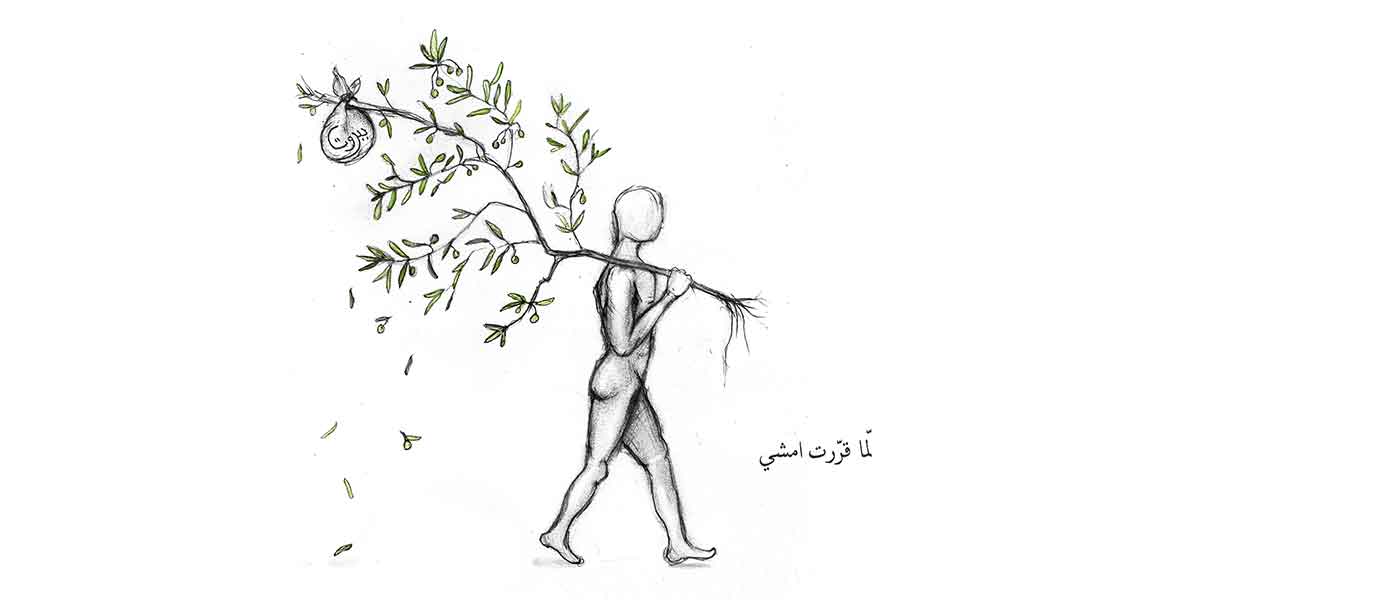

After his passing, a single thought emerged from the blur: “I want to go home.” On a visit to my mother’s grave, my brother had once mentioned that he wanted to be buried next to her in Croatia, and now, I wanted to take him there. I had to sit in my grandmother’s yard where we had played, where we picked ripe figs each summer, where he accidentally spit on his birthday candle that one time, extinguishing it at once.

My brother was in a little box now and my father put it in the back seat, on a beautiful gold-flecked tablecloth. It was the only kindness he could show his son anymore. The airport was bustling and indifferent, life going on as it always had, even though my carry-on was full of ashes. As the plane descended toward Sarajevo, my father and I both wept silently, our sorrow bottomless, my brother at our feet. The city welcomed us with ten friends, there to hold our hands and carry our luggage, some there only to kiss us once on each cheek, as was the custom.

Settled in at a friend’s home, my father told and retold the story of what had happened. We all hung our heads, cigarette smoke swirling around us. It made me sick but it smelt familiar. “This wouldn’t have happened if we’d never left,” my dad said. Nobody answered. I thought it might be true but wouldn’t say it out loud as the words were too ugly. My brother had been in Bosnia weeks prior, with the family we were staying with now. They had taken a picture together with a big white cake, celebrating his 21st birthday. It’s still there, his smiling face and theirs. I hated it the first time, but I love it more every time I look at it.

Friends drove us to Orebic the next morning, a serpentine trip through sloping hills. As we got closer to my grandmother’s house, shimmering scales of water emerged from the trees, slowly at first, then quickly filling up the turquoise horizon. A family friend who had survived the siege of Sarajevo had told me that when she thought she might die during the war, one of her biggest regrets was that she might never see this view again. It calmed me for just a moment.

We arrived at the house and opened the sagging door, pulling up and then pushing in, as I had learned to do for the last decade. My best friend opened the door and though I had not seen her in two years, we said nothing. She stepped back so I could enter the living room where my grandmother sat at the table, glossy photos of our family, my brother, swallowing every inch of it. “I haven’t seen you in a long time,” she muttered and showed me a picture of him taken weeks earlier, palm leaves framing his head like a halo. We discussed the floral arrangements being delivered for an inordinate amount of time, just making noise so we wouldn’t be alone with our thoughts. We ate dinner together, made tasteless by misery, drank too much, and retired to a restless sleep.

The view from the cemetery was stunning. Amorphous islands dotted the sea, the water sparkling and seemingly endless. We walked to the grave cautiously, my best friend holding my hand. My brother’s godfather, sensing my dad was unable to speak, said a few words about his childhood, about how simple and kind he was. We had all loved him, an incomparably sweet and gentle soul. As the box was lowered into the gravesite, my grandmother screamed, throwing her arms forward, as if attempting to catch him, to draw him back to us. Mute, I stood on the hot concrete, watching the sickly scene unfold, a faux American burying her brother in a land that was once Yugoslavia, where my heart belonged. It felt hot, and I was home. That I could comprehend. I was in a place I hadn’t wanted to leave and hadn’t wanted to go back to. Now I knew I didn’t want to be anywhere else, numb, but still breathing.