繼

My mother and I are in the storage room behind her children’s textiles gallery, the lights dimmed so as not to damage the displayed fabrics with overexposure to light. The storage room is chilly, made more noticeable by the constant double-whirring of the air conditioner and dehumidifier, which are always on at full blast since the textile pieces need to be in a temperature-controlled room. We are surrounded by shelves of clear plastic bins labeled “hats,” “bibs,” “shoes,” “tops,” “baby carriers.” Large reams of fabric on rollers line one side of the room, and in the aisles between the shelves are garment racks with children’s clothes hanging from them. Sometimes, when I walk within the aisles, I accidentally bump the racks and the metal charms hanging off the hems of certain jackets tinkle like the distant sound of children’s laughter. Tassels and charms made from metal, grains, or seeds are often sewn onto children’s clothing like this because the noise they make is a way to ward off evil.

Currently, we are sitting at the desk inside the storage room, which runs the length of one wall, and we’ve taken down one of the bins labeled “children’s clothes” from its shelf to examine its contents. As my mother unearths a child’s jacket made of yellow silk, padded with cotton and adorned with traditional Chinese knot buttons, she splays it gently across her open palms. She then flips it around to reveal a drawing of a tiger in black ink. It’s not a particularly old article of clothing, nor is it decorated with the intricate embroideries or appliqués of many of the other pieces in her collection that always elicit gasps of disbelief from viewers when they look closely at the handiwork likely performed by the wearer’s mother or grandmother. But there’s something in the freedom of this jacket’s design and the wantonness of drawing directly on silk with a calligraphy brush that spoke to my mother when she first acquired it in Beijing years ago, a relic from the northern region of China. In addition to the tiger, there is also a meandering geometric pattern painted along its borders.

“Maybe this mother was just very good at brush painting,” my mother says in Mandarin. “The point is, she didn’t care whether or not painting directly on fabric was ‘right.’ That takes a sense of courage. To me, this is innovation.” I am recording my mother’s voice and taking notes as I listen. I’m not sure what I will do with these notes, but recently, I have come to feel an urgency in collecting them. Already, I have begun to regret not recording my children’s voices more often. I didn’t know how quickly I would forget the tinny raspiness of their kid voices, the way they mispronounced words, the way my younger son lisped. Or, it’s not that I’ve forgotten, because I can still imagine their faraway little voices in my head — it’s that when old videos pop up, their sounds send something electric up and down my body, a mix of intense love and wistfulness. Perhaps it’s the same impulse I feel with my mother: It is not enough to simply have a record of her thoughts. I also want to capture her voice, hear its pauses, and make her thinking audible.

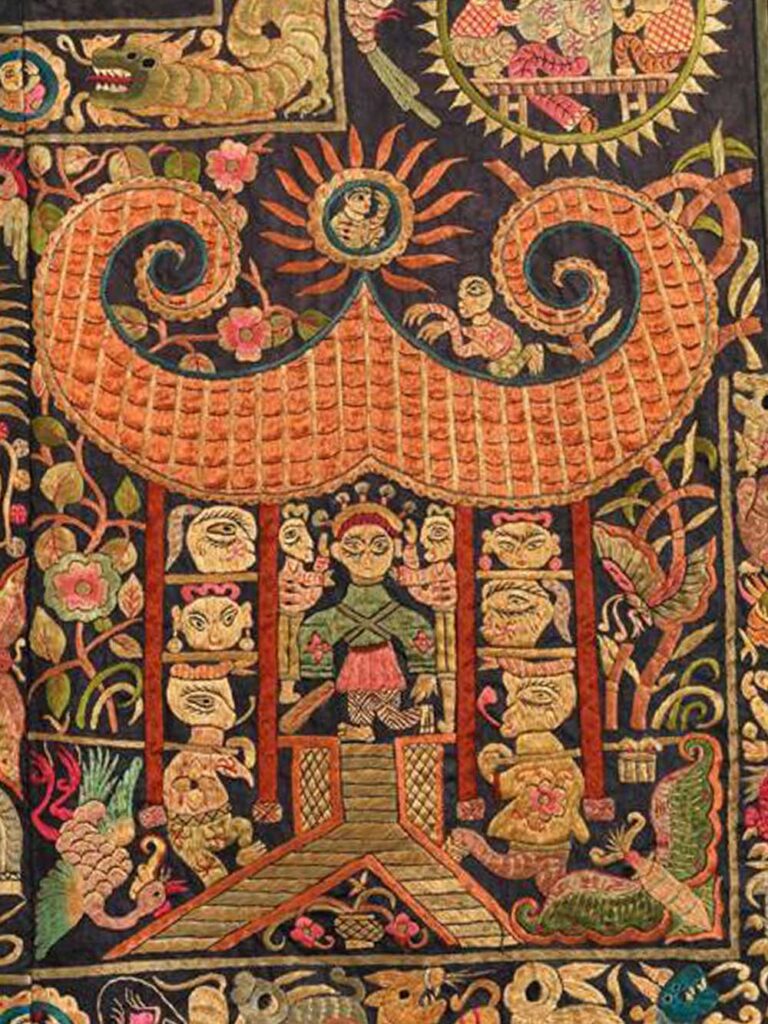

My mother brings out another jacket, and this one is large, from the Shi Dong Miao tribe, sold to my mother by a Miao woman named Pan Yuzhen. Pan was anointed “Inheritor of the National Intangible Cultural Heritage” in China twenty years ago and often travels the world to speak about the traditional Miao art of embroidery. The jacket looks dirty with age, and both its front and back are filled to the borders with an array of embroidered beasts, including the twelve Chinese zodiac animals, an elephant-looking beast, a dog-beast, a horse-like animal, lions, dragons, butterflies, and Pan Hu: a being that is considered one of the ancestors of the Miao people. Also embroidered on the front of this jacket is a gate, under which sits a figure holding a pipe. This is likely the shaman whom the Miao believe is responsible for guiding the dead back home. The craftsmanship and intricate stitchwork is so fine, I feel it can only be from a time before the advent of mass production, which ironically robbed us of the long stretches of time it would take to focus on work so minute and painstaking. Because of this, my mother always wears white cotton gloves when she handles her collection; she doesn’t want the oils from her fingers to damage the textiles.

“Actually,” my mother tells me, “this jacket is from the 1990s. It was merely made to look old.” I look closely at the darkened parts of the jacket, and its sootiness does look suspiciously uniform. I am reminded of a middle school history project I once did, staining paper with tea and searing the edges with a stick of incense to make it appear like an ancient scroll.

“You know,” my mother continues, “it’s possible this was made to look older to sell to collectors who aren’t aware, for a higher price or something. But I know what’s going on and for me, it’s part of the charm. I’ve made friends over the years and have never felt swindled. Plus,” she says as she touches the embroidery with her finger, made large and awkward by her ill-fitting glove, “look at this handiwork. And look at the stories that fill this jacket. See how this beast is carrying this young boy? In Miao culture, there is no difference between the real and the fantastical.” She repeats this anecdote often, reminding me not to allow our increasingly technologically dependent way of life to close off our view and understanding of the spiritual world. For many Indigenous tribes and peoples whose lives are intertwined with nature, the membrane between the physical and spiritual world is thin or even nonexistent. It is precisely because they live so closely to the earth that they don’t forget the magic that surrounds us as we do. For them, the portal to the spiritual world can be opened; this fluidity between the worlds is expressed through stories and recorded on fabric in intricate detail. It amazes me that embroidery — a craft that requires so much time, repetition, and patience — can produce imagery that is this playful and light.

Though my mother always wears her gloves, I resist the impulse to do the same when I am alone with her fabrics; the tactile experience allows me to appreciate the labor that has gone into each article of clothing, and wearing gloves only dulls my senses. I don’t touch the pieces in my mother’s collection with my un-gloved hands in her presence, of course, as that would be disrespectful, but the next time I return to my mother’s storage room on my own, I fold the jacket and put it away in its bin with bare hands so that I can feel the textures of its threads — satin stitches filling a large area creating a bulging effect, knot stitches that stipple the surface. The feeling of its handiwork sends a real surge of energy through my hands — it’s as if touch can activate the memory of this work being done, stitch by stitch.

These two jackets are emblematic of how my mother views the inheritance of cultural craft and traditions. She studies the history of cloth-making in different cultures in China and Taiwan, but what truly excites her is how tradition changes over time, how each generation takes what they have inherited and transforms it into something new.

Inheritance can be an awkward thing. My mother and I are in a phase of transition now: Her collection is being passed down to me, but it is not yet mine. It requires a letting go on my mother’s part, as much as it requires an openness on my part to fully receive it. I have watched from the sidelines as my father transitions out of the family business just in time for my older brother to take his place at the helm; from this exchange, I’ve learned firsthand how succession doesn’t happen the way it does in stories, where roles change overnight. The process is slow and non-linear, like stitching that often needs to be taken out, sewed backwards, in order to right its way.

The conversations my mother and I have in her storage room are now a meaningful part of her developing ritual of letting go, her transference of stories and memories. A few years ago, I suggested we digitize my mother’s collection as a way to archive and index: We took professional photographs of each of the two thousand pieces in her collection and uploaded them onto a data-organization platform. I then asked my mother to write notes about each piece: what year it was made, what materials were used, the kinds of embroidery stitches that were employed, what each symbol and motif signified, and about the stories behind each image. Because the pieces in my mother’s collection are all children’s textiles made by mothers and grandmothers, the images often convey blessings and wishes for good fortune. And because of Han Chinese influence on minority cultures in China and Taiwan, wordplay is an oft-used motif; for example, bats show up repeatedly as a motif because their name shares the same pronunciation as luck (fu), so her notes usually contain explanations of Chinese homophones like these. But perhaps most importantly, her notes also include when and how she collected each article, because this is information only she possesses.

My mother spends at least a few mornings each week in the storage room doing exactly this: going through her collection and pecking out notes on the computer. She says spending time with her textiles brings her joy. Sometimes, I join her so I can record our conversations and make my own notes, but most of the time, my mother performs this work on her own or with the help of her longtime assistant.

My mother is doing her part, but am I? Most days, I feel unworthy; other days, I feel indignant, like a sour-faced, ungrateful teenager. Sitting in that small storage room, surrounded by so many textiles — the colors, the evocation of animals, the seasonal flowers, the homophones, all of the motifs evoking abundance and continuance — I toggle between wonder at the physical metaphor for life, and the physical and temporal burden of archiving and caretaking.

The Shi Dong jacket we examined earlier is about thresholds: the liminal space between life and death, between the physical and the spiritual worlds. I am reminded of the image of the shaman embroidered on the jacket now — how he is sitting underneath an archway, the swinging door between life and death, ready to guide the dead toward their final resting place.

Inheritance is a kind of threshold, too, though it is unclear whether or not it is guarded by its own shaman.

In fairytales, inheritance is often a central theme; most of the time, it is presented as a reward for successfully completing a test of loyalty and love. A father (who is sometimes a king) with several (usually three) children will divvy up his possessions before his death, and while doing so, something will be revealed about the sincerity of his progenies’ love for him. The revelation is usually that the child who is most indifferent to the inheritance is the one who loves the parent the most.

As for my own reluctance to absorb my mother’s collection, I have been forthcoming about it to her. One of the reasons I suggested the digitization project is because it would make it easier to sell or donate the collection one day. My resistance feels unfilial; proof that I am failing some test. But if — as in the fairytales I’ve consumed — a child’s loyalty and love toward their parent can be validated by their very rejection of said inheritance, or, at least, their diluted attitude toward its priority, then maybe I am a good daughter after all.

Or maybe I have been asking the wrong question all along: Maybe it isn’t about whether or not I want to receive my mother’s inheritance, but about how my mother wants her inheritance to live on. How should her collection continue to exist without her? Does she want me to love it as much as she does? When I ask her this, she says she has no expectations — that regardless of whatever I want to do with the collection, she will be at peace.

Why does this feel like a test?

In terms of understanding the kinds of textiles my mother collects, I am a layperson — or, at best, my knowledge can be compared to that of someone who is just starting to learn a new language: they have a grasp of basic vocabulary and pattern recognition, but are still lacking in confidence and breadth of sentence structure. Even so, I have begun to feel something stir within me — something beyond the information I am gathering from the papers and books that used to take up my mother’s bookshelves in my childhood home, which are now finding their way onto my office desk and shelves: books on embroidery, symbolism, and dyeing (its homophone a stark reminder).

It is a common platitude to say that you cannot truly understand something until you are immersed in it yourself, but nowhere does this ring more true than in the experience of becoming a mother. Within the different stages of my own experience of motherhood, I’ve constantly recalled things my mother once said or did, particular facial expressions she wore that were cryptic to me in my childhood, but which have since come to mean something I understand on a visceral level. I now know why, for instance, she took French and Japanese classes in her forties, became a docent at the National Palace Museum, and read tomes of art history books, engaging in a multitude of activities to enrich her life — full as it already was from her being a mother and a career woman.

Growing up, I remember wishing she would spend more time at home instead of going out to business dinners or night classes, but now her doggedness in preserving a part of her that wasn’t merely defined by her role as a mother inspires me. Now, in my forties, I find that my mind is also famished for intellectual and creative pursuits that are my own, apart from my responsibilities as a mother. Perhaps most astonishingly, all the little things my mother did in silence to keep our home together are now rendered visible to me — things as mundane as keeping the pantry stocked with her children’s favorite foods, calling the plumber when there is a leak in the bathroom, and knowing at any given moment which child’s finger- and toenails need to be trimmed — because these are the very things I do now. In tandem with these actions, a collection builds from small moments — like changing a sick child out of soiled clothes in the middle of the night, or collecting their artworks, writings, and handmade cards into piles of keepsakes for the future. All of this requires a quiet and almost stubborn patience. This is why I don’t like the term “maintenance labor,” as it is applied to motherhood, because it is so much more than that.

In her book, Women’s Work: The First 20,000 Years, Elizabeth Barber writes about the history of weaving and the inordinate amount of time it once took to spin and make cloths for one’s family. She reminds us of the difficulty in studying this history, which dated as far back as 15,000 BC, because textile fibers so easily disintegrate over time. In many ways, then, “women’s work” — spinning, weaving, embroidery — is a beautiful metaphor for mother’s work. It requires time, patience, and a complete surrendering; in this vein, I think of the long, quiet hours my children used to nurse. But mother’s work is also effervescent, as are textiles — none of my children remember being thus tied to me and in fact, find it embarrassing to speak of.

A mother’s work is far more than maintenance, just as inheritance is far more than a one-time act of transference; it is like weaving and embroidery: textile arts that require quiet, insistent repetition, but which ultimately produce something magical and surprising.

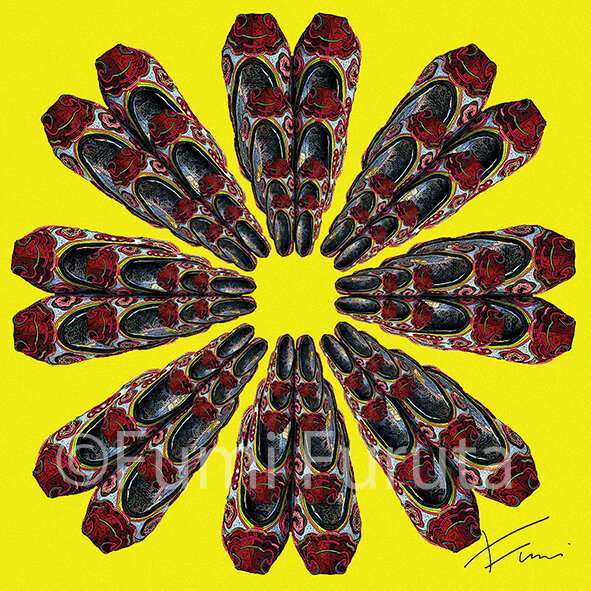

In March of 2019, I helped my mother stage a portion of her collection for an exhibit at the Beitou Museum in Taipei, titled “Stories Told Through Mother’s Hands — Children’s Textile and Embroidery Arts.” It was a streamlined show, beginning with examples of the four “female arts” (weaving, dyeing, embroidery, and patchwork) before moving into the meaning of signs, symbols, and woven folktales. Finally, the show culminated with a room full of traditional clothing from my mother’s collection, paired with modern clothing from our family’s children’s-wear company. In the hallway next to that were canvases of digital artist Fumi Furuta’s manipulated photographs, inspired by the children’s shoes in my mother’s collection. These were examples of the innovation in inheritance my mother was talking to me about back in her storage room. What propels us forward is innovation, but this must first come from a deep knowledge of — and respect for — tradition.

During the exhibition’s opening, a simple press event was held, during which a journalist asked my mother which one of her pieces was her favorite. She joked that it was like asking which of her children was her favorite — the point being that it was impossible to answer. But the reporter, not wanting to give up, turned to me to repeat the same question. My answer — and this is the honest truth — was that my favorite thing about my mother’s collection was not a single piece, but the time we spent together as she told me the stories behind each and every article: how the things we held came to be, the people she’d met who made or sold them, and where she’d journeyed to acquire them. I reflected then on how mothers do so many things that their children don’t see or ever know about, but in this case, I had the rare opportunity to be a part of my mother’s ritual of transference and inheritance — to witness our inflection point, holding onto one another before my mother lets go completely, surrendering so I might pick up where she left off, recording the next chapter of our story in my own way.

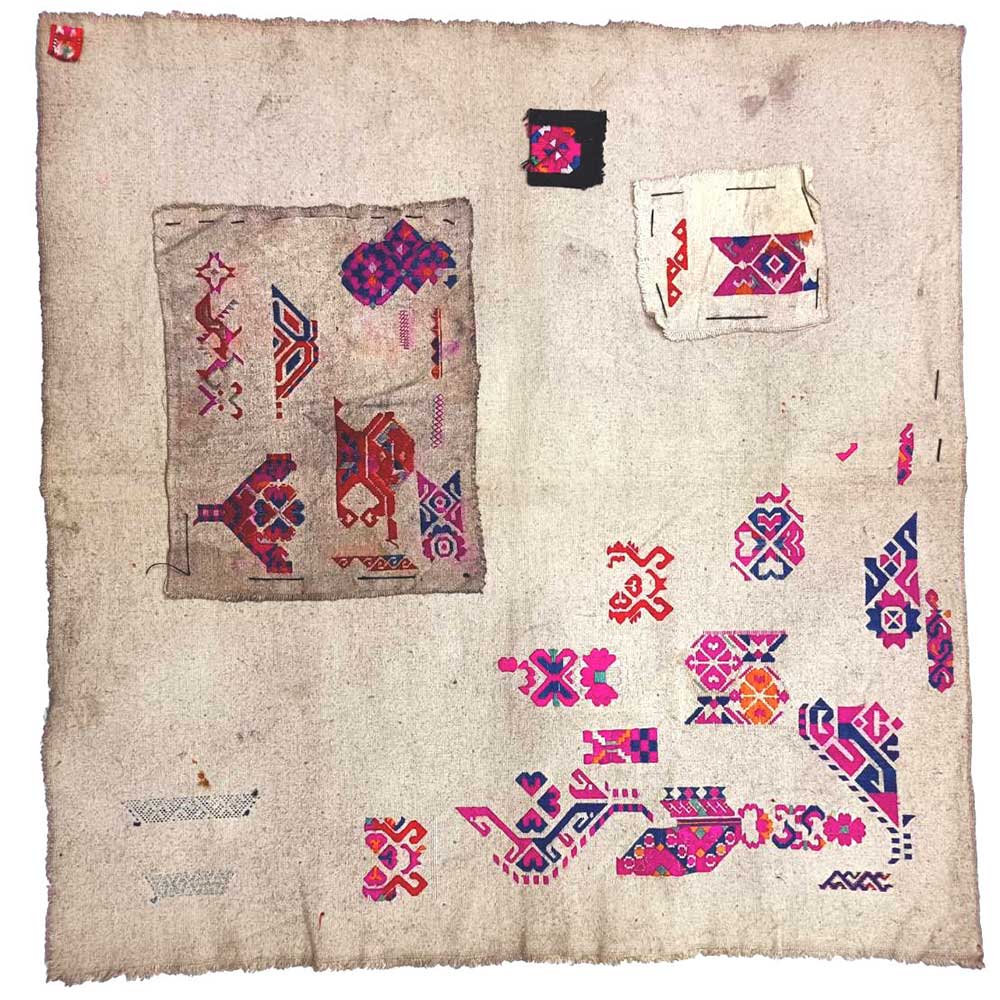

What I don’t tell the reporter is that I do have a favorite category in my mother’s collection. It is her smallest collection: a series of stitch guides known as 子母花. 子母 means child-parent and 花, usually translated as flower, also means embroidery. These scraps of fabric are sewn with a woman’s library of stitches that she passes down to her daughter, so that her daughter may reference her mother’s craft. Later, the daughter will add her own unique stitches to the catalog and pass that down to her daughter.

Especially in cultures without a written language, these stitch guides are the lexicon of a family’s history and emotional vocabulary. In truth, every family speaks its own private language, but most of us just don’t record it. What a beautiful notion to be able to stitch fragments of this private language onto a piece of cloth that you can hold, running your fingers along its raised bumps, reading them like Braille. What if, when you ran your fingers along the embroidery, you could hear the voices of your ancestors?

My daughter has always played with her stuffed animals in a maternal way, swaddling them in little blankets, rubbing their furry bellies and tucking them into bed each night. Her bed is next to a window that looks out into our backyard, and she likes to push back the curtains to look at the moon before saying goodnight to me and to the stuffed animals in her care.

My daughter is at her most tender in the dark, when we are alone. She likes it when I rub her back or throw my leg over her, putting weight over her body so that she can feel the heaviness of gravity, of our bodies being here, right now. When she has an upset stomach, I rub Tiger Balm on her belly in a clockwise motion to coax out the trapped air. Before turning out the lights, she often asks me to clean inside her ears, putting her head in my lap so that I can swab gently with a Q-tip. In these moments, I feel the weight of her head pressing into my lap as her entire body relaxes. More than once, during these intimate acts of caretaking, my daughter has wondered whether women receive handbooks on how to be a mother when they have their first child. I tell her no, but I promise to pass on to her everything I know, everything I’ve learned from my mother and my grandmothers.

Lately, I have been thinking about my daughter’s question in earnest. Should I write a book for my children, or maybe stitch a 子母花 ? When I first took up stitching, my daughter was about seven years old and wanted to stitch with me. After I taught her a few basic stitches, I gave her her own embroidery hoop and fabric and access to my small array of embroidery floss, which I kept in an old cookie container. This is what she stitched:

As I stare into the image of this piece, it suddenly dawns on me that it resembles the stitch guides in my mother’s collection — it also occurs to me that as I stitch the proverbial (or actual?) 子母花 for my children, I already have one in my possession that my daughter has made for me. Hers is embroidered with all of her embodied knowledge, which I recall from the journals I kept for her when she was young, before she started writing in her own journal every night. I think to myself that I should put this handful of starry wisdom in my pocket and call upon it whenever I am feeling lost.

- when my daughter was three and we were cataloging things we were grateful for, “me, by myself” was her number three;

- when she was four, she told me she knew that after we turn one hundred, we brrrrrrr and become zero again;

- when she was five, she told me everyone has three eyes: the two that we see and a third one on our forehead that’s used to look into people’s hearts;

- when asked if she wanted to go up to the moon, she said, “No, I like my feet on the ground.”

In Lewis Hyde’s book The Gift, he writes that “threshold gifts” (gifts that accompany moments of change) are perhaps the most common type of gift we give and receive. They are gifts that punctuate specific milestones in the cycle of life such as birth, graduation, and marriage; they have “two sides to each exchange and to each transformation: on the one hand, the person approaching a new station in life is invested with gifts that carry the new identity; on the other hand, some older person — the donor who is leaving that stage of life — dis-invests himself of an old identity by bestowing these same gifts upon the young.” In this way, inheritance is the ultimate threshold gift, as one has to pass through the final stage of life — death — in order for their heir to fully possess that inheritance.

Hyde also writes that one of the essential properties of a gift is that it must remain in motion, either through changing hands or through consumption, so that it also changes property and energy. It stands to reason, then, that inheritance must be among those gifts that move most dramatically: it passes from one generation to the next as the giver moves from one realm into another, from the physical into the spiritual.

The Chinese character for inherit is made up of five knots:

繼

The radical for silk or thread is on the left: 糸. On the right, there are four smaller knots ㄠnestled in a structure that might resemble a loom. A horizontal line marks a break between the top two and bottom two knots, suggesting that in order for something to continue, it must first be cut off.

I am then reminded that to continue in Mandarin is 繼續, which is the character for inherit followed by the character for connect. 續 also bears the radical for thread because in its original meaning, it was used to describe rope or threads that could be linked. I am astounded when I notice that next to the thread radical is the character to sell. Is this a sign — a directive embedded within the text?

Or perhaps, the line in the tiny loom in 繼 can be seen as the threshold between the physical and spiritual realms — the swinging door that infuses an inheritance with the movement and energy Hyde describes as the essential property gifts possess in order to retain their value and meaning. I recall the embroidered shaman on the Shi Dong jacket, whose figure inspired me to wonder about shamans of inheritance. I hold an image of it up next to the hoop of my daughter’s stitching.

And suddenly, I see it: At the threshold of inheritance, there are, in fact, two guides: the giver and the heir. It is my mother and me, together in her storage room — she is talking and I am listening, as our fingers move along the bumps and grooves of embroidered threads, feeling our way together. Just as, every day, I hand my daughter a tiny star of maternal experience for her to sew into her stitch guide. Because the only reason I know how to be a mother is because I am a mother to her.

I don’t know whether we will continue the work of archiving the collection, sell it, or give it away. Inheritance is so much more than the material thing being passed on. It is the cumulative time my mother spent gathering each object of love, it is my translation of her collection through writing, it is my daughter’s stitch guide. Right now, I’m uncertain how my mother and I will emerge from her storage room — but when the time comes, we will both know.