—for E

Dust remembers what we try to forget, preserves the hidden, and keeps evidence in wait. Dust is composed of dried peas knocked down the side of the oven, the brittle bodies of dead crickets, lint left in the dryer. A favorite glass broken, breast milk spilled, a snail shell I shattered with my foot. Other remnants of violence, too: the dried blood and skin and dander shed by my cousin’s body, mingled with aluminum shavings shed from the crumpled frame of her bicycle. Spray from missile testing in the desert. Comminuted fragments of my fibula, plucked by the surgeon from in between the swell of blood and the ropy tendons, replaced by cadaver bone and titanium screws. Household dust from blue bleach drying on the grout and the acetate sequins from my Dorothy Gale costume, relieved of their color and shape. Microplastics filling the air, the water, our food, and our waste. Fragments of viral DNA.

The satisfaction of drawing a finger over the green leather-bound books my grandmother mailed me, of gathering the dust on the rough whorls of my fingertips, holding so much of the world there. Dust preserved my great-aunt’s false jet beads, the gleam of the facet visible underneath the wooly layer of grey.

Dust has a long memory, and not just for objects. We once used dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (easier to say and simpler to remember as DDT) to save our soldiers from swollen blood cells that burst and inflamed the body into malarial fever. DDT must have seemed a miracle: soft, crystalline, without taste or even scent, with the ability to catch mosquitoes in a sharp, electric spasm and then death. But we humans breathed the poison too, swallowed it thoughtlessly, drew it into our tissues and organs and bones. Our skins grew yellow with lesions, our fingers gnarled, our livers failed, our fallopian tubes twisted. The DDT hid in the soft waiting spaces of our reproductive organs and in our dust.

Years after the ban, scientists tested undisturbed dust, hiding behind cabinets, chairs, and shelves, and found DDT, smiling, in wait.

This is the failure of my brain, what makes me vulnerable to a magician who draws short white threads from her pocket and crumples them into her fist, then smiles at me as she unfolds her fingers to reveal one long thread, miraculously intact. If I cannot see the trick, I cannot believe it exists.

In magic, a vanishing act is when something passes from being into non-existence. The particles we breathe perform the opposite: they are nothing at all to be seen, and bloom into life when they enter into the body.

After my grandfather’s funeral luncheon, I retreated to his closet, exhausted by too many voices, by birthday cake and funeral potatoes. I folded myself between his good pressed pants and his beloved sweatshirts, and breathed. Everything past and present swirled inside the house, carried through ventilation, trapped in corners, by filters before they escaped outside. I took a deep breath and inhaled crumbs from my mother’s home-baked bread, good church shoes with Texas dirt on them from the cemetery, fragments of the white and aqua hydrangeas that we had to take home — no living flowers were permitted on those graves. All of this dust held life and death, made from the soiled bedclothes, the flaking skin, his thick white hair unspooling from his scalp. I held his last days in my lungs, breathing in the Ativan and the morphine drip, the hospice nurse and his last, wan smile.

Lately, when I go to the grocery store, I breathe through a two-layer cotton mask, hot pink on the outside, dancing flannel kittens pressed against my mouth and nose, hiding my lipstick. My mother made these masks for me and my siblings: my brother’s was a blue cowboy print, a relic from a vest she sewed for him as a child. The mask’s interior is threaded with guitar wire; I pinch it around my nose.

The air holds dust of every size: gray flakes drifting off a dirty ceiling fan; fine, bright particles drifting from a bonfire up the canyon; and viruses, suspended in their delicate, crystalline droplets, tumbling to surfaces, caught up in air, stirred, silent, waiting. The novel coronavirus, lovely in its scarlet spikes and rippling body, is held in those drops. For how long, and in what form, no one seems quite certain.

Air takes the path of least resistance, explained one of the scientists at work (my job is to take their numbers, their equations and indices, and shape them into words). Any gap, any lessening of a defense, and the air will plunge forward, anxious to sleep, to sag (lazy air, spilling into my nose, infecting the kittens).

Lately I have learned to make images as well as words for the scientist. The original diagram was a tangle of sharp arrows meant to represent how a virus — any virus: influenza, coronavirus, rhinovirus, adenovirus — can migrate into a nurse’s respiratory tract, onto a doctor’s hands, and into the mucus membranes where it takes hold.

I chose a dotted and fluid computer brushstroke, and drew the air looping between near-field and far-field, onto surfaces, onto open palms and into respiratory tracts. Because a virus cannot be seen, the scientist measures transmission using fluorescent tracers that irradiate the body, the gloves, the gown, the stethoscope under black light. Presto! The virus appears. It is on telephones and IV poles, on the bedside, on the wrist beneath a glove, on hair, on the skin beneath the scrubs.

These days, scientists can number pieces of dust — all the better to guard our lungs against infiltration. The lab across from my office holds gray boxes tucked into black foam, white boxes, blue boxes, instrumentation designed to calculate the count and mass and concentration of dust of every size, injectors to fill the air with dust, wind tunnels to spiral it back and forth. My favorite is the Grimm, for its evocation of Hansel and Gretel, breadcrumbs dropped and failing to preserve the way home. It costs $25,000, and can neatly sort dust into 31 different bins and count them along the way. Like any good instrument of divination, it is fickle, and clots with iron oxide, garbles numbers, and sometimes suspends its counting for minutes at a time, silent and resentful.

Downstairs, silent in the wind tunnel laboratory, a mannequin’s torso hangs exposed. When he is turned on, his skin warms and he inhales, then exhales. Manny, as they call him, is of course male (these things are always male, assuming normalcy of that body alone). He is mounted inside the wind tunnel on a rotating device. Aerosols are injected into the chamber, and the mannequin turns, toothless mouth pursed, and rotates in order to achieve an even exposure to dust.

I worry about him, breathing as he does Arizona road dust or aluminum oxide, teaching us how dust settles inside the nose and the throat, how well different monitors work, and if he can be protected with a mask. He is cleaned in between experiments with a clean wipe, and therefore forgets himself.

Manny gets a companion one day, a citrine-colored resin model of the nose and lips, modeled on a CT scan of a healthy eighteen-year-old boy. His face opens like a puzzle; lift the outer tissue, and inside is the rippled etching of the nasal cavity. I balance this boy in my hands, careful not to drop him, wondering what he will be contaminated with, what infections he will model and refute. Another scientist experiments with swabbing his nose, testing to see how many particles the cotton can collect, and if she needs to intrude more deeply to understand him.

Dust is classified into three categories. The first is that which stops at the ears and nose, halted by tiny hairs and the trap of mucus membranes, like the soft sticky pads that hold mice until they starve or sink. The intrusion of this dust is met by a flood of histamines that irritates the brain, causing the muscles of the nose and throat to spasm into a sneeze. In 2016, riding the London underground for the first time, I continually found a soft, black, sooty material inside my nose and ears. I wiped it away, puzzled by the Victorian remnant.

Particles that move past this guardian system are called thoracic: they traverse into the larynx, nestling into the throat and the tissues that lead down to the lung. But the last category, the respirable, is made of dust miniature enough to float and settle into the pillowy lungs and the alveoli can ride a rush of good air into the bloodstream. Enough of this dust, and the rates of pneumonia rise, especially among the elderly; their lungs attempt to wash the dust away and instead drown themselves. Much like in incidences of miscarriage, a fetus expelled amidst a rush of blood and tissue; the failure of the heart to pump its blood, sputtering and seizing into silence; lungs and mouth gasping for air, airways constricted unless a steroid frees them.

Dust makes us even as it unmakes us. Hydrogen — that delicate, simple atom — forms on interstellar grains of dust to make a new galaxy. It swells and spreads, spun into life by collisions. Hydrogen survives in a bath of ultraviolet light. It remains intact through photo-dissociation, or when photons bombard a molecule until it is unknown to itself. Hydrogen and dust both remember themselves, even after transformations.

Some of the smallest pieces of dust result from ordinary life — my favorite lavender shortbread candle, the quick snap and riot of a lighter, the ash that follows silver fountains and blooming flowers in July, the coals shimmering red with heat, burnt corn silk and marshmallows and fragments of onion. Even walking past a fragrant, silent cloud of cigarette smoke (a smell I secretly love, that I would drink if I could), I breathe in that dust. I inhale these particles in my kitchen, the olive oil spitting off the steel pan, the pot of browning butter as I count the amber speckles, the milk fat slowly turning gold. The soft hiss of hair spray, the smallest traces of rose oil in perfume.

But the poorer a person is, the more likely they are to inhale tainted air. Some live with wood stoves; with bright disinfecting sprays, laden with bleach; with exhaust spilling through the windows from the furnace, from the outdoors. My home county of Salt Lake is split by a broken vein of highway between east and west, white and brown, poor and wealthy. That line is seamed by the petrochemical corridor that spews butadiene and formaldehyde. The air grows thicker with dust from industrial sites, illegal dumping areas, and wind-blown heavy metals.

The Salt Lake Valley sits in the cupped palm of ancient Lake Bonneville, flanked by the Oquirrh and the Wasatch mountains. The lake left behind soil rich with sand, gravel, coal, and copper — their mining has etched long, bare ridges into the mountains. Lake Bonneville is emptied now, but the shape of it remains. Most people call it the inversion, a smothering presence that relinquishes only to rain. Cold air presses down on the warmer drafts in the bowl of the valley, letting all the poison pool there. One night I left a sushi restaurant, unable to see my companions through the mingled fog and pollution, thick enough that it seemed as if I could fasten my teeth around it and take a bite.

Scientists call these nights air pollution events, a performance at which we all gather around and applaud. Some days I can taste the acridity, a sourness that can’t be banished, the scent of wood smoke and alcohol and something wrong. When I drive up the canyon, I can see the inversion, a sinister blanket folded over a sleeping infant. The dust hangs over the city, clouding familiar landmarks, towers and buildings, the smokestack visible only from the highest points.

Everyone in Salt Lake, I read, is high-risk for the coronavirus because of the air we breathe. The black lungs I see at work are not from cigarettes, as my 1990’s DARE teacher promised me, but by the dust. Scientists say I will likely lose a year or two of my life to it.

Rain and wind are our only saviors, sweeping the dust away or catching particles in the air, weighing them down, trapping near-invisible fragments in the bubble of a raindrop. In Beijing, drones equipped with nebulizers rise into the sky and spray, trying to carry pollution to the ground. Presumably, it will then enter the groundwater, evaporate, and enter the sky again.

Last November, a nearby enterprising ski resort seeded clouds with silver nitrate, once called lunar caustic (a white fall of baking powder, of moon dust, ground and dispersed with a single exhalation). The nitrate, they claimed, produced snow. It must have worked, since skiers crowded the roads to Big and Little Cottonwood canyons that season, their skis and boots strapped to their cars. On their way there, they passed air that once held my cousin and her detritus, now taken up again by aspens and marsh marigolds.

Silver nitrate can cure sexually transmitted diseases, clear away infected skin, and, if ingested in certain quantities, provokes a condition called argyria. Once enough silver is taken in, the skin begins to illuminate itself from within, turning permanently blue-gray. There is no cure.

Each day I read about a new organ the novel coronavirus can disrupt — the lungs, fibrotic and stiff, able to hold less and less air. The heart, drowning in its own fluid. The kidney, cycling dirty liquid, in and out, then floating motionless, surrendering to a machine. The brain failing, neurons twitching, muscles of the face drooping. The blood continuing to clot before a surgeon’s disbelieving eyes — transfusion upon transfusion, the body seeping blood faster than it can be replaced.

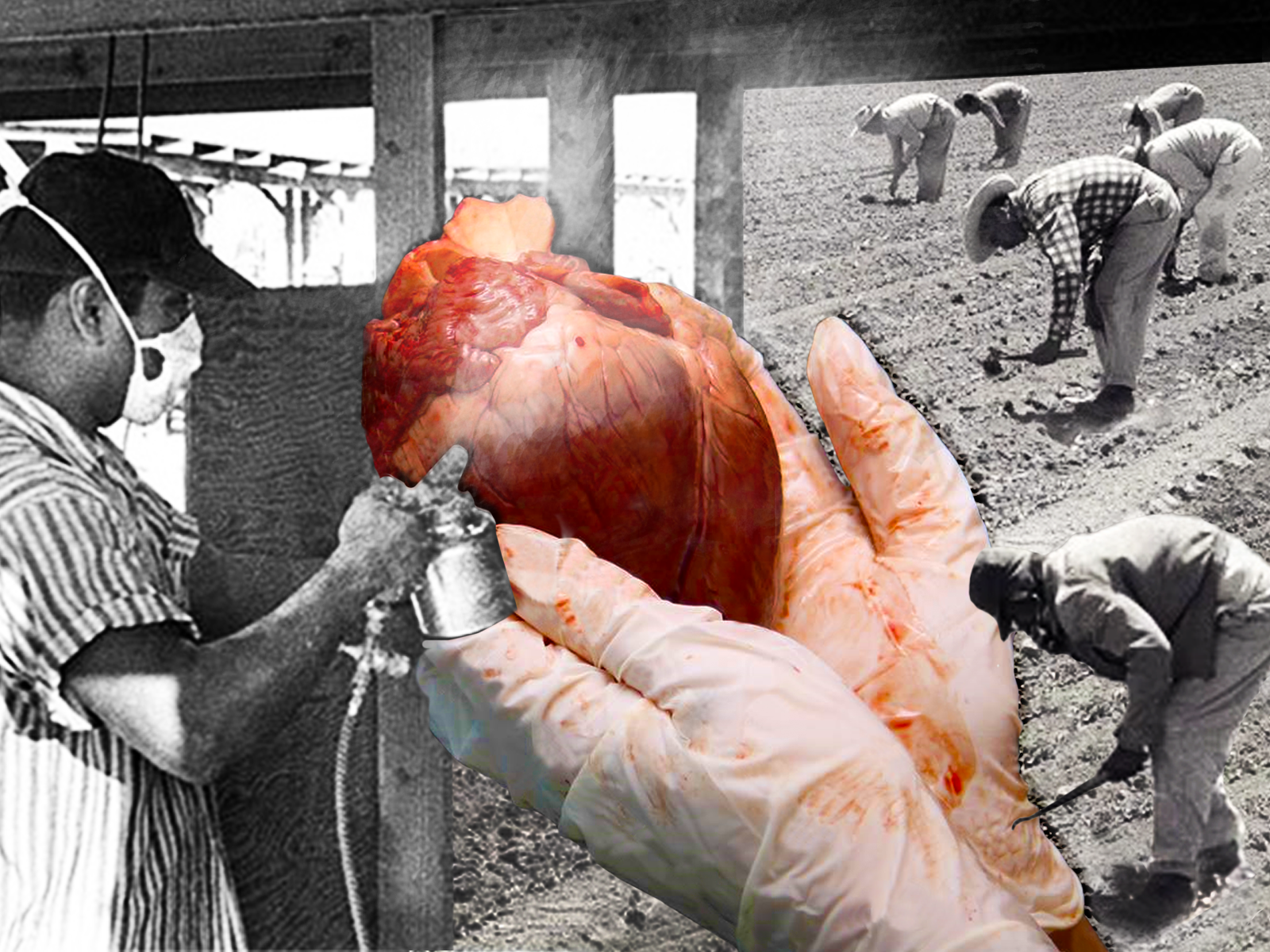

I have only to inhale a thousand particles of the virus for it to enter me. A sneeze or a cough can fill the air with thousands more, even millions — the virus proliferates, riots, blooms, and spreads. But I know it likely doesn’t even take inhalation — the virus could touch the clear surface of the eye, be blinked into the lacrimal duct, where the tears flow to the nasal cavity, and there it can begin. Scientists in France infect lovely, golden-brown rhesus macaques with the virus: they are killed after 10 days with paralytics and anesthetics. Scalpels and saws cut through the fur, open the flesh, crack the bones to witness the lungs laid bare. The dissection allows the scientists to follow the spread of infection from eye into throat, from throat to lung, its swollen pattern reaching down further and further into the body. All this so we understand why we cannot touch our eyes.

In 1926, the last water from Owens Lake was distributed to Los Angeles, and the lake became desiccated, flattening into a dry marsh of the clay, sand, and minerals that had once threaded through the water. The minerals concentrated themselves into a delicate crust of arsenic, cadmium, nickel — when the wind spiraled over the lake, it carried the remnants to the people that now drank the water of Owens Lake. The metals were small enough to slip down their throats, into their lungs and their blood, into their hearts and brains and nerves.

Now, we plan to divert the waters of Bear River before they can enter the salt-edged shores of the Great Salt Lake. Already the minerals and metals condense on the crust of the lake, crushed by the harvesters of brine shrimp. Later, when the water has turned to nourish us and our fields, our plants and throats, the red-winged blackbirds and the long-billed dowitchers will have no place to rest, and we will breathe the dust. A hundred years, or fifty from now, my home may be nothing but shimmering flats of salt. What is left of us will be caught and spin in the air, the fat of the atmosphere stripped, the dust storms wearing us and our belongings smooth as stone, anxious for us to join them.

Nuclear fallout, another apocalyptic future, is the spread of radioactive dust and particles from shattered buildings and organic matter. Such dust does not drift predictably: fallout from Chernobyl drifted from Sweden to Norway, reaching out to graze the world’s face. Animal after animal (sheep, reindeer, cows, and boar) was slaughtered that year to prevent the unruly spread of radioactive remnants — a slamming bolt between the eyes, a slash of the knife; lift and burn and bury the buckling flesh, wash away the sticky swirls of blood on the floor (don’t think about how those corpses re-entered the air, sparks from the crematorium, particles from bones gone dry). Who’s to say what might have happened if they didn’t? Even 33 years after Chernobyl, we search those animals for the radioactive trace, and, in an attempt to heal them, set them on clean pastures. Nedfôring, they call it. Feeding the meat and milk until the poison is diluted.

I am thinking about Chernobyl — about poisoned groundwater, about how even the plants had to be eradicated — one morning at work. One of the scientists, the only other one with long, straight hair like mine, stops by my office with a warning. If nuclear fallout occurs, she says, we should stop using conditioner on our hair. I read why later: radioactive dust can slip into the damaged crevices of hair opened by the water. Conditioner will trap and hold it, and contaminate our scalps, our skulls, our neurons and synapses, our mitigating frontal lobes.

The coronavirus exits the body in a weighty droplet that tumbles as soon as it is expelled (except, perhaps it doesn’t; perhaps the droplets are lighter than that, delicate globes of liquid containing tumbling infection that can drift through the air, through the dry, frigid air carried from room to room). We take measures to contain it: veils of heavy plastic, negative pressure airflow, blue and yellow tents enveloping the emergency room by my house. When I visit my orthopedic surgeon, I look in at the nurses through their clear, unnerving halo of a face shield, their mouths concealed with the soft blue accordion of a surgical mask.

I read advice on how to wrap a length of pantyhose over a homemade cloth mask and pull it close, preventing both egress and ingress (I love these words; they sound to me like enormous white birds careening over the shore). Do not enter. Do not exit. My glasses fog up in the grocery store. I hold my breath when I pass by people, almost without thinking, even knowing better. I cannot see their breath, but at least I believe it is there.

I am so porous: I used to think of my body as something contained, which nothing or no one could enter. Now I know I contain galaxies of other beings: a swirling microbiome of bacteria that nourish themselves on the food I eat; delicate spores of fungi growing and bursting, viruses with their corkscrew tendrils, outnumbering my cells, sustaining me. I remember a melancholic pop song I used to love — The Air You Breathe is Full of Ghosts, a cry for the lover to enter into the beloved’s lungs and live there. My love and I breathe each other, the dead pieces of each other’s skin and hair, yes; but also the particles containing each other’s microorganisms, our crumbling shoes, our skin, our hair, the plant pollen we breathed after hunting foxglove and gentian by Lake Mary, the puffed spores of the silver mushrooms we found there instead, the decomposing carpet beetles that chewed ragged holes in our sweaters and then perished.

My love is immunocompromised, body eager to attack her skin, intestines, bile ducts and liver. Every eight weeks she injects her abdomen with an antibody that muffles certain expressions of her system, silencing them before they can riot, inflame, and scar into irregular walls inside the body. In spite of this concoction, her body still flames, sometimes, into delicate red whorls inside and out, into ducts strictured into the eye of a needle, veins tightening themselves into small fists. We are both afraid of what the coronavirus might spark in her.

After I come home from the grocery store, I drop my clothes into a tight pile and step inside the shower, standing under the falling water, willing the water to weigh down any particles, to hold and deposit them into the pipe and the water swirling below my feet.

My childhood cocker spaniel’s ashes are held in a plastic bag, twist-topped, contained within a red velvet one. The bag yields in my hand like a stress ball, squeezed to calm myself. Penny weighed 18 pounds while alive, and I can barely feel the weight of her in my palm. When dogs are cremated, their bodies are placed with a tag that will not burn, and the burned bones are recognized by the presence of the tag. I imagine five neat piles of dust: a German Shepherd, a Yorkshire Terrier, two Labradors, a Border Collie, and Penny, wrapped in her blue blanket.

Cremains are not dust, at least not initially. The last step of the cremation process is to shatter the bones, sift them, then pulverize them again, so that if a curious mourner dips their fingers in, they will not encounter the greater trochanter or the distal radius, but merely the soft, even dust that might gather atop a bookshelf.

Mourners in Japan are less afraid: they pluck the bones with chopsticks, arrange the beloved from feet to spine to skull. We make bodies into dust to comfort ourselves, to eliminate the fungal celebration of a body decomposed, the waxing blue-green beard that covers bare skin. Better dust than the waxy figure of my cousin, draped in her funeral white dress, her mouth sealed shut with too-pink lipstick.

On Disneyland’s Haunted Mansion, riders often covertly dump ashes from the rocking cars and onto the ground. Cast members try to catch them on tape and vacuum the dust away, but the dust mingles, unable to separate from each other. Riders inhale these bodies with their open mouths, laughing at the spinning holographic ghosts.

Ashes, of course, are not organic material. If a seed is planted into ashes alone, nothing will grow. That’s why I want to be buried intact: let me crumble into the soil, good sweet richness for something to grow from.

I stand outside on my porch in the mornings when I feed our feral cat, a gray girl who, after four years, will finally let me stroke her neck and massage behind her ears while she eats. I inhale with my nose, practicing my good breathing. The breath fills my belly, moves up to my chest, rushing down into my lungs. My cells make the switch quicker than I can believe, carrying rich, dark oxygen to my organs, feeding carbon dioxide out to the air around me. I breathe again. I used to believe, when I was younger, that my body could forget how to do this one, simple, necessary thing. Now I know the movement is inscribed in cells and encrypted in the organs, and will fail only when I do. But still it feels a gamble or a curse.

Turn me silver, drown and blacken my lungs, ruin my kidneys, or weaken my heart. Whatever happens, I take another breath.