Mama was born in the year of the Dog. In the Chinese Zodiac, dogs are known to be loyal and stubborn, of which she was both, but mostly I thought of her as brave. She had a freedom about her, a spontaneity I didn’t possess.

The night of my first high school breakup, I went with her to Safeway to get groceries for the week. She breezed in through the doors labeled OUT while I plodded the long way to go through the doors labeled IN. I hadn’t told her about my heartbreak. She didn’t have to ask. I was cocooned in a hoodie, shuffling my feet. I pushed the shopping cart like it was the most tiresome chore in the world, drifting 15 feet behind her.

Thunk.

A loaf of bread landed squarely in the cart.

“Like my 3-pointer?” she asked, waving proudly from the other end of the aisle.

I sighed, “What are you doing?”

“Ooh, let’s have hot dogs this week!”

Th-thunk.

A bag of hot dog buns bounced off the corner of the cart onto the linoleum floor.

“Stop! We’re gonna get yelled at!”

“Ok, fine. Hamburgers?”

Swshhh…

A bag of hamburger buns came arcing toward my scowling face. By the time I caught it, I was irritated to find a smile had upturned my mouth.

“We’re out of English muffins,” I muttered. Then laughed as they vaulted towards me.

In my memory of that day, I don’t remember how it felt to be sad about a boy. I remember laughing with Mama, carbohydrates soaring through the air between us.

I wanted to be like her in so many ways. She had the ability to turn gloomy moments absurd, mundane moments memorable, public spaces her personal stage. If she felt like singing on the sidewalk, she’d belt. If she wanted to cheer up her moody daughter, she’d play basketball with bread products. I played the part of teenager and acted embarrassed, but I also admired her audacity.

There were days I felt embarrassed of her for other reasons, like when her usually flawless face erupted into hives, eyes swelling and nose bright red. It happened often enough that I grew used to it, and while the flare-ups didn’t scare me, I did wish she’d lay low for their duration. Instead, she’d put on sunglasses and go about her day unperturbed. “It’s my punishment for being vain when I was young,” she’d say.

It was actually a punishment from her favorite food – she had an allergy to shellfish, but nothing could keep her away. Ever the optimist and gourmand, she brought home bushels of live crab every summer. We’d cover the dining table in newspaper and upturn pots of their bodies, freshly boiled and steaming, their once-blue armor flushed red. She’d crack them open with glee, dipping the succulent meat into ginger, soy sauce, and vinegar, sighing in satisfaction with each tangy bite. The aftermath was never on her mind.

When her hives were at their worst, I volunteered to help with errands. She stayed in the car while I hopped out to mail packages, return videos, pick up art supplies. Usually lost in my own world, I stepped up on those days because I didn’t want people looking at her when all they could see was her skin condition. I hated the way they stared. Like she was contagious. Like they were afraid of her.

The first time I remember hearing the term anti-vaxxer was in 2014 while hosting dinner for new friends. We munched on sticky California dates stuffed with cream cheese, wrapped in salty slips of bacon, while chatting about jobs, relationships, and the breathtaking sunset outside the window. I braised a chicken with Mediterranean olives and lemon, and as I retrieved it from the oven, the conversation turned to recent news: a measles outbreak in Disneyland.

We expressed shared dismay as we carved the chicken and ladled its juices over hot, buttery rice. Across from me sat a young man I’d met before a few times. He worked at one of the big tech companies, which impressed me, and he tended to be outspoken. He shook his head, bemoaning, “Anti-vaxxers! Can you believe we let dangerous idiots like that be parents? What kind of assholes don’t care if they’re infecting people with their disgusting children?”

My mouthful of chicken suddenly tasted sharp. I chewed and wondered – had I put too much lemon in the dish? And also, was I one of those disgusting children? Had Mama been an “anti-vaxxer”?

When I was born, I had my first round of vaccinations just as my two sisters before me had. Unlike my sisters, though, I had a bad reaction, and from the way Mama described it, my family almost lost me to the ensuing sickness. She told the doctor thanks, but no thanks, for future rounds. I didn’t catch up with my immunization schedule until adulthood.

I passed the salad and kept listening. Mama didn’t fit the anti-vaxxer description I was hearing. She never proselytized, never mentioned autism as a feared side effect. But she also couldn’t forget staying up all night to monitor my high fevers and listless infant body, couldn’t shed the fear of life leaving that body altogether. I wondered if I should try to describe any of this to my new friend, to add more nuance to his idea of a type of person. I waited for a pause to add my voice, but before I could, he concluded, “Anti-vaxxers should just die. That seems like the only fit punishment.”

My cheeks burned, heat stemming from a place between shame and hurt, and as the others laughed, I lost the nerve to speak up. I smiled and refilled water glasses instead. The borders of the room had shifted, enclosing those with experiences in common and placing me on the outside where I could look in, but not be seen. I didn’t want to share anything about my upbringing with this acquaintance; I couldn’t imagine him understanding. Besides, Mama had already received her punishment.

After that dinner, I noticed the term “anti-vaxxer” popping up more and more in social media posts. At first, I scrolled past them, reasoning that I was immunized now, so what did these stories have to do with me? I couldn’t deny my past, though, so I pinned the articles and told myself I’d read them later. I kept putting it off. I also started guarding that part of my life, not letting information about vaccine hesitancy out or in. As someone who tries to be socially conscious and is usually an open book, these behaviors were odd for me. I started to dig within – what was I hiding from?

Growing up, the feeling of being on the outside was a familiar one to me. There weren’t many Asian Americans in the places my family lived, and I was, on occasion, greeted by fingers pulling eyes back into slants, nonsensical imitations of Asian languages, and jokes about my people eating dogs for breakfast.

I also had an atypical school experience: I attended a tiny Waldorf school K-12 where we wrote and illustrated our own textbooks, recited poetry daily, and did farm work as part of the curriculum. Kids I met outside of school asked me if I was in a cult. I said no, but could tell from the way they laughed that it didn’t matter. The things people want to believe about you often hold more power than what you try to tell them. As a kid, I learned to stay quiet around those who laughed at me, and to retreat to like-minded circles.

At my new-agey school, I almost certainly wasn’t the only unvaccinated student. I never felt strange about that part of my life there. The national conversation was different then, too – while doctors told my parents that it would be safer for my health to be immunized, I don’t remember anyone ever talking about risks for the greater community. No one told us that when less than 95% of the population is vaccinated, herd immunity can be negatively impacted. Growing up, I worried about things like stepping on rusty nails, but never about contracting and spreading the measles.

To be completely honest, I may even have prided myself on a strong immune system. If people were surprised when they learned I was unvaccinated, I pointed to the fact that I’d been fine all these years. On the other hand, Mama had been vaccinated, but was still often visited by mystery symptoms. Aside from the hives, there were skin conditions that stiffened her fingers into claws and coughs that left her breathless. Once, a small lump appeared in the palm of her hand, and after a month, out fell what looked like a seed. She was tempted to plant it in the garden.

Though she visited doctors on occasion, they didn’t quite know how to identify her ailments. She always ended up with a generic prescription to something that gave her uncomfortable side effects. By the time I came along, her third and final child, she’d only see a doctor when nothing else worked, and she didn’t put much stock in their counsel. She trusted her body to tell her what to do.

When I moved away to college and then across the country to California, I’d come home holidays to sometimes see her navigating a new ache or pain. For the most part, she took any discomfort in such stride that we couldn’t even tell when something was wrong. But things can be fine one day, even many days, and then suddenly not be.

One New Year’s Day, I was confused to come home to a wisp of the woman I expected. She couldn’t speak loudly because she was having trouble breathing. Her belly was swollen from a blockage in her colon, and her cheeks were sunken from having no appetite. A couple weeks before, she had given in to my dad’s pleadings to get X-rays, and they revealed shadows on her lungs, liver, and colon.

After the X-rays, she delayed returning to the doctor, saying she would rest first and get stronger before undergoing any procedures. But she had only continued to weaken. The morning after I flew home, she agreed to go to the hospital. She cracked jokes with the nurses as they got her settled, and we talked only of her getting better. The doctors would ready her for an operation to clear her colon, and then we’d take care of the shadows, one by one. My middle sister stayed with her overnight, reporting to the rest of us minute-by-minute. Mama was hydrating with ice chips. That was good. Mama was calling out Baba’s name in her sleep. That was sad but sweet. Mama was asking to go back home. That was heartbreaking.

She would never make it home. She died in the hospital the next day, her husband and three daughters surrounding her.

At first I was angry with the doctors. Why hadn’t they been able to save her? Why didn’t they know what was wrong? Then I was angry with myself. I shouldn’t have moved so far. I should have kept a closer eye on her health. Then I was angry with her. Why didn’t she go in sooner? Why did she always have to act so brave, like she could handle everything herself?

Retracing all I knew about her, I found the answer in a part of her life I’d almost forgotten.

She’d told me about her childhood in China, but I’d filed it away under family history that didn’t have much to do with our lives now. At the time of the telling, I had yet to set foot anywhere in Asia, so when she recounted stories of her life there, it sounded like an alternate world. She sounded like an alternate self, a little girl from a foreign fairytale. It never occurred to me the things that happened there were still within her, guiding her movements. As I reflected on stories she’d told me, one in particular kept resurfacing:

She is seven years old, little but strong. She waits outside her house for her grandfather to come home from work, scratching pictures in the soil with a stick. A dog comes into the yard and she perks up at the prospect of a new playmate. But there is something strange about this dog, the way he skulks and stumbles, the tension about his shoulders and jaw. As she pulls back, he lunges forward and bites the soft section of her upturned forearm. Skin breaks. Blood colors her sketches in the dirt.

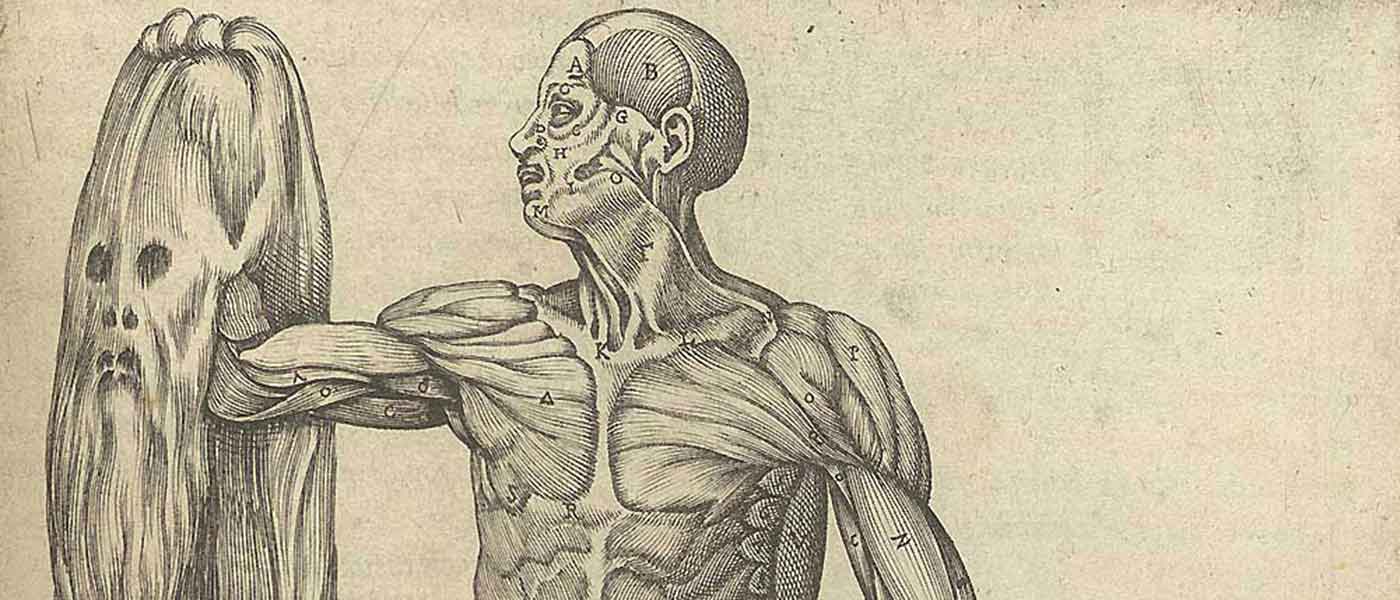

The dog runs off into the woods, and Mama is surrounded by a flurry of concern. Neighbors are checking her eyes and shouting in panic. Someone whisks her out of the village, into the nearest city, taking her to a strange place: a bleak concrete building, where she is seated on a metal bed with straps of fabric hanging off the sides. “Don’t be scared,” they say, but Mama, who has never seen electricity or hospital instruments or people in white uniforms before, can’t put her fear away. She lurches off the table to run, but the people in uniform grab her roughly and throw her back onto it. She tries to wriggle away, so they grip her with their strong hands and use the straps to tie her down.

One of them comes towards her with a long, silver needle, and she screams as it plunges deep into her stomach. She has never felt pain like this before – it is not the pain of a fall, or a cut, or even the bite of a dog. It is much sharper, deeper, a startling and intrusive pain. She begs for it to stop, but the needle comes back down again, again, again, again.

It wasn’t bravery, I realized, that made her stubborn about shouldering illness by herself. It was trauma. She had a phobia of needles, of doctors, of hospitals. That’s why she didn’t go in for regular checkups. That’s why my first bad reaction to vaccines made her want to protect me from any further needles. And I, lacking the drive she had to go off the beaten path, had continued along the one paved for me: the path without vaccines.

Once I located the source of Mama’s decision-making, I wanted to separate her trauma from my next steps. It was time to take control of my health. I called the closest physician. She told me I could come in right away.

That afternoon, I sat facing a doctor with a kind face and steady hands. As she laid out her instruments, my mind told me I was afraid. It wasn’t my fear, though, but Mama’s, that I had absorbed. In my head, I told her I would be alright. She didn’t need to worry about me anymore.

“This will feel no worse than getting your ears pierced,” the doctor said reassuringly.

With each sting of the needle, I felt a sense of relief, each prick unpinning one of Mama’s fears from my body.

It is a rite of passage to confront the fact that sometimes our parents were wrong in their choices for us. That even the people we idolize can be mistaken. I still want to be like my mother in so many ways, still want to love and honor her. But I want to make different choices.

In a time when there are clear lines drawn between who is right and who is wrong, who is good and who is bad, who is sane and who is insane, to acknowledge my medical history is to place Mama on the side of wrong, bad, insane – Mama who I have missed every single day since she passed ten years ago.

Whether we use the label anti-vaxxer or not, the fact remains: I was not vaccinated during my childhood. If I had been born today, I don’t know if she would have chosen the same. I’d like to think not, but there is no way of knowing. I know, though, what would have helped and what would have hindered: information imparted kindly by people she trusted and respected would have helped. Being mocked and ostracized would have hindered. A doctor who listened to her trauma and provided her with patience and reassurance would have helped. Being labeled and shamed would have hindered.

I’d been scrolling past vaccination posts because I was afraid to see Mama or myself in the anti-vaxxers my friends were expressing hatred towards. Their words triggered a shame in my upbringing that I instinctually ran away from. Once I realized what was happening, I moved the shame aside so I could inform myself.

Now if someone vaccine hesitant wants to talk, I can tell them what I’ve learned from readings they may not seek out themselves. I can share that from my experience, there’s no need to fear routine vaccinations, little justification to shirk this important social responsibility. The possibility of that conversation may sound inconsequential, but for some, it could make a difference.

The pattern we find ourselves in these days is not conducive to conversation. The stakes feel high, so we get loud. The higher the stakes, the louder we get. The most outspoken of us have adopted a method of communication in which we broadcast articles with snarky headlines that reaffirm our stance, accompanied by commentary that is designed to ridicule those who don’t share our views. We are providing information, but surrounding it with barbed wire. There is no chance for growth in this structure. We are breaking connections instead of creating them, further isolating those who have a different experience.

It’s become a social norm to make disparaging jokes about groups we can all agree are illogical, unintelligent, or wrong in some way – a coping mechanism to diffuse the fear we have of those we don’t understand. We are forgetting that the reasons for their seemingly illogical views probably stem from fear too. Fear is stoked by shame and hatred, dispelled by knowledge and understanding.

To get to any kind of understanding, we have to remember we are all more complex than the labels we affix to one another. Mama was more than the stereotype of an anti-vaxxer. She was brave and fearful, empathic and fierce, solemn and silly, impulsive and indecisive, rebellious and traditional – full of color and contradictions as we all are. In this time of division and misinformation, the most courageous and productive thing we can do is to remember each other’s humanity. To remember that we are more than dogs.