Vignettes of/with the Russian Dictionary of Imperial and Soviet Prison Slang

“It seemed that the incommensurable gap between the Soviet police state and the benevolence of American law and order was an illusion, that objects had been rearranged and images distorted, but the overarching carceral structures remained the same.”

—“Refusing to Bury the Living,” Egina Machalova

“My tongue and your tongue are already an aggregate, a site of multiple and collective enunciation.”

—Translation is a Mode=Translation is an Anti-neocolonial Mode, Don Mee Choi

TO AMNESTY YOURSELF (АМНИСТИРОВАТЬ СЕБЯ)

To successfully escape [from prison].

ANTICHRIST (АНТИХРИСТ)

Bailiff’s assistant.

I spent my first decade of life outside Moscow, born to Soviet parents from

Ukraine and Russia. I cannot precisely trace the histories of my ancestors

further back than my grandparents’ generations. The carceral muscle of the

State, the silence it cultivated, have erased them.

When I started this piece in late 2021, the war continued its 7-year simmer at

the Eastern borders of Ukraine. Since then, Putin’s army has flattened entire

Ukrainian cities, thousands of people, into the earth. A border you can’t cross

back from.

A border — at least for empires — is a site of perpetual violence, a tool for

its justification. Inside a border of a State is always another border.

Between 1930 and 1955, the USSR contained the GULAG archipelago — a system of

penal labor camps raised around the Union’s entire geography.

Around 1,700,000 people died within it, shrouded in layers of official quiet.

The final room in Moscow’s GULAG History Museum is an audio exhibit.

A voice reads out a list of the victims’ names. Though the recording lasts for multiple hours,

the list, the voice warns, is incomplete. Some records are still

sealed, others the State destroyed.

But the language, never entirely containable,

moves between spaces of louder and quieter secrets.

*

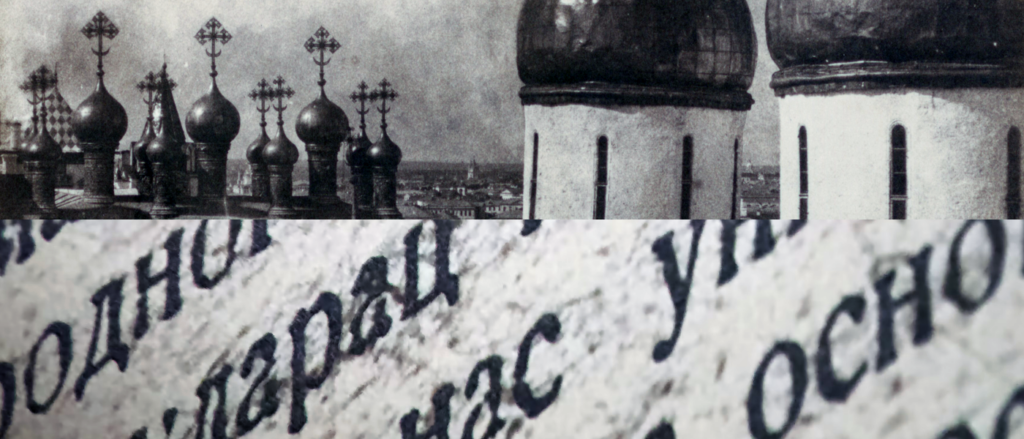

ALTAR (АЛТАРЬ)

the judge’s bench

Leonid Gorodin, the compiler of this dictionary, was born in Ukraine in 1907.

The State imprisoned him 4 times.

From one of his memoir-essays, Ginger Man:

“One time, when we were getting booted to work, [another GULAG prisoner] — caught in his preparations — lingered in his corner for a moment too long. The guard fired off curses towards him. That was the first time I heard his clear, calm, slightly sad voice: ‘What are you shouting at me for? I’m not your slave, I’m a slave of the State.’”

ACADEMY (АКАДЕМИЯ)

- prison, penal colony, arrest; the “school” of thieves — “It’s not for nothing uncle’s house is known as the university, called the scammers’ academy” (Smirnov).

- the occasional gathering of gambling swindlers.

*

QUESTION (ВОПРОС)

A political prisoner — “[in 1879] … In Moscow ‘students’ [likely: ‘lazy, useless people’] and ‘questions’ were not yet well-liked or understood” (Seroshevsky 207).

POWER ON YOUR SIDE (ВЛАСТЬ НА БОКУ)

A revolver in a side-body holster — “He has power on his side, — meaning a guardsman’s Nagant, Khan answered” (Leonov 45).

AIR (ВОЗДУХ)

- An untruth.

- Money.

- Thieves’ surveillance.

- A bribe.

*

“A dictionary is a whole world, its own kind of spirit universe.”

NEWSPAPER (ГАЗЕТА)

A bat or an alternate tool for beating.

TO TEACH A LESSON (ДАТЬ УРОК)

To sentence [someone].

TO MAKE (ДЕЛАТЬ)

To completely subjugate someone to your will by means of beating and torture — “You know how the thieves in [prison] camps made these [people]? They made them lick boot soles [and] the toilet bowl” (Adamov 101).

TO ARRIVE (ДОЙТИ)

To become weak, to completely be emptied of strength, to die (recorded in carceral institutions of Vorkuta, 1937-1950; recorded by linguist I. Revzin in Moscow Oblast, 1956) — “The general has arrived, has become thin, resonant, and transparent” (BANNER 171).

In a pedagogy of punishment, pain is the lesson materials form to serve.

TO BREATHE (ДЫШАТЬ)

- To receive packages or gifts, especially regularly.

- To speak.

When the ones watching are those who send notes from your children,

pressed burnt orange maple leaves from a walk near your home. Some

cigarettes.

Then, in your letter, in a brief break from the toll this space takes on your

body, you find not air, but something more like what you used to call it,

something you might allow to enter you.

Some “questions,” though, received sentences “without the right to

correspondence.” Often, the State used this language to hide from family

members that it had executed their loved ones. Stealing their breath.

TO TRAVEL TO THE SKY THROUGH TAIGA (ЕХАТЬ НА НЕБО ТАЙГОЮ)

To lie incessantly.

TO PRESS [SOMEONE] (ЖАТЬ [кого])

To take a non-violent inmate’s parcels, gifts, or belongings by force.

TO STOP BY (ЗАЕХАТЬ)

To find the right way to approach someone.

LAWFULLY (ЗАКОННО)

From beginning to end, in entirety.

Everything but the law is a process. To be “lawful” is to be already in

the past.

TO PLAY THE VIOLIN (ИГРАТЬ НА СКРИПКЕ)

To saw at the prison bars.

TO GO TO THE GRASS (ИДТИ НА ТРАВУ)

To escape from captivity.

ICON (ИКОНА)

- Photograph

- “The internal rules of order” in a colony (Nikoronov 78)

BEAUTIFUL (КРАСИВЫЙ)

Person raised in an orphanage — “The waifs call people raised in orphanages ‘beautifuls’” (Shishkov 46).

*

WING (КРЫЛО)

Arm.

BARK (ЛАЯТЬ)

- Ringing of the bell that calls the inmates to work

- A verbal altercation, fight

BUTTER — SUGAR — WHITE BREAD (MАСЛО — САХАР — БЕЛЫЙ ХЛЕБ)

Highest possible appraisal of material goods available to inmates.

WINDMILL (МЕЛЬНИЦА)

- Talkative person

- Gambling hangout — “‘Windmills’ were the main hangout for various criminals” (Gilyarovsky 393)

- One of the entertainment sources inside a prison — noise, screams, banging. “The frightful wailing, the desperate whistling, the wild banging of fists and feet… This sweetening of hearing goes by the name of ‘windmill’” (Gernet 63)

- Live-in female partner

MUSIC (МУЗЫКА)

- Conventional language of thieves

- Engagement in snitching and espionage. “An accusation of espionage inspires terror in the prison; we’ve seen inmates cross themselves and swear in front of a [Christian] icon, when their peers suspected them of (the so-called in prison slang) ‘music’” (Yadrintsev 95)

- Tea

Like everything, music lives in context. How do you hear

what can fly, what makes air move in circular currents

the way breath might move through a body?

GARBAGE (МУСОР)

- Policeman, an agent of the CID [Justice department] — “I’m surprised that the garbage hasn’t smoked you out [of the train station] yet” (Levi 20)

- Traitor, secret informant, snitch (in Yiddish, “moser” means informant)

TO TURN [SOMEONE’S] FACE OUT (НА ЛИЦО ВЫВЕРНУТЬ)

To identify someone; to find out someone’s real last name (Vorivoda 71) — “You, artist [scammer], sit [in prison], we’ll turn your face out” (Polevoy).

UNHAPPINESS (НЕСЧАСТЬЕ)

Gun, pistol, revolver, firearm.

SPECIAL ORDER (ОСОБОЕ РАСПОРЯЖЕНИЕ)

At the start of the Great Patriotic War, all political prisoners nearing release were held in penal camps awaiting “the special order.”

Waiting is the favorite word of orders.

Source material: “Dictionary of Russian slang lexicon of labor camps and penal colonies in Imperial and Soviet Russia,” Leonid Gorodin, Publishing Project of the GULAG History Museum and the Memory Fund, 2021