Beyond dead. Torsos glazed with epoxy, exuding an icy sheen. A spinal column exposed, its flimsy cord dangling from a robust sacrum. Saffron-tinted skin peeled to reveal formaldehyde-soaked livers, spleens, and stomachs. These wide-eyed mannequins — now the centerpieces of famed public exhibits — were fabricated bone by bone, layer by layer, using human tissues and other raw material taken from the dead.

Standing corpses fill several exhibition rooms at the Providence Convention Center in the fall of 2016, just one of the many locations around the world that showcased, and continues to promote, the lucrative “Body Worlds” exhibit and similar displays. The dancer, a specimen lacerated to demonstrate symmetrical perfection of flexibility, right leg outstretched, aiming towards the poised head, is one of the bodies erected to stand before hundreds of visitors.

Nearby, a body is shaped into the form of soccer player in motion — outstretched leg aiming towards the ball, muscles rigid, eyes narrowing in on the goal. In the same room, a “bionic” body reveals multiple prosthetic joints and metal implants in the hip, knee, elbow, and spine. Drawing attention to the femoral implant as part of the hip joint, surgical scissors have been inserted into the thigh. In this figure’s back, two-foot long forceps split open the skin, revealing a metal rod that has been inserted parallel to the spine.

The body portrayed as a diver is sliced longitudinally, liver and heart suspended so they appear to hover between the two halves of the body, which is split open in the shape of a “V,” each section ready to take the plunge. The accompanying text reads, “The body shell of the diving figure has been split in half and pushed apart to offer a simultaneous view of the trunk muscles and inner organs in their natural position.”

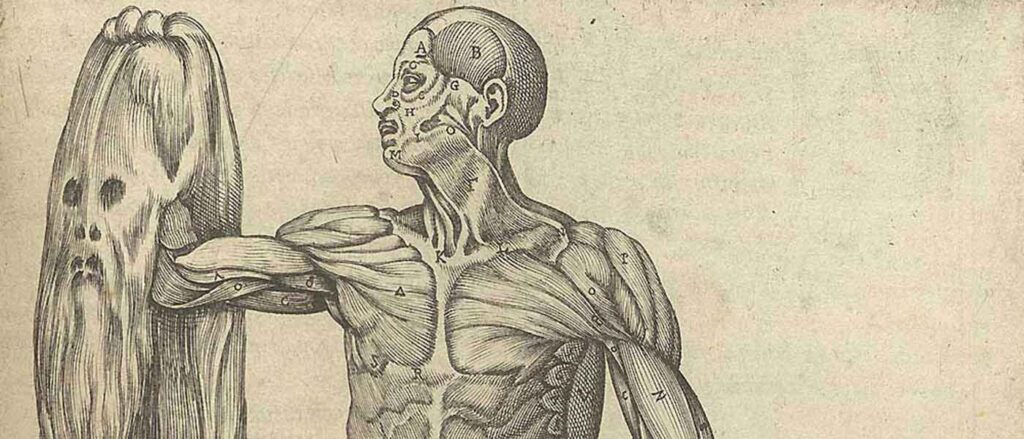

History has its place in this exhibit, which is billed as an educational experience. “The Man Who Holds His Skin” is a modern day version of an early anatomical illustration, Juan Valverde de Amusco’s “Anatomia del corpo humano” from 1559, a figure of a muscular man holding the entirety of his skin which is draped over his right hand.

Cross-sectional gashes of flesh jut out from splay-legged plastinates, outlining the glistening spirals of intestines, wholly intact, their marked curves precisely defined. In a room dedicated to pregnancy and newborns, a fetus tethered to its sac is suspended in the air as part of a series depicting a baby’s development. Separately in a nearby case, a healthy knee joint sits next to an arthritic one, a raw and swollen surface that looks like a hambone.

To ready corpses for displays like these, they will need to undergo an elaborate sculpting process. Unlike the rites of passage that most cadavers undergo, these source bodies are dismembered and dissected, then recreated into new identities. Their tissues and bones are meticulously solidified, molded, and sculpted through a process called plastination. There is no guarantee that the body’s original tissues will be used to create this new figure; parts from other bodies may be incorporated. Resin encases these figures for an estimated four-thousand-year life span, transforming them into polymer mummies embalmed for millennia to come. There is a question of whether decomposition will ever occur as their cells are consumed by plastic.

What is known about the plastination process is that disassembled parts extracted from the dead are mixed and matched to create new human-like figures that are shipped overseas to ultimately stand on display for the curious. Consumers around the world will buy tickets for thirty-five dollars (or equivalent) to peer inside these shells. Other valuable parts, especially organs, can be extracted and sold before the bodies are prepared for display. It’s reported that hundreds, if not thousands, of prisoners of conscience from China, those who have been persecuted by the government for their political and/or religious beliefs, have become the raw material used to assemble the standing dissected.

Since 1995, when the first public exhibit opened in Tokyo, bodies and parts have fed the demand for both anatomical research and public displays throughout the world, becoming a lucrative business for plastinators. In museums in Berlin, Germany, and Dalian, China, and as part of traveling exhibits run by entertainment companies, consumers of this entertainment have spent over $200 million since 2004 to attend these showrooms.

Is there suitable vocabulary to discuss figures that have been engineered from disparate human parts?

Medical school graduates and other factory workers in China are employed to manufacture these corporal entities, working at more than 100 companies specializing in this field. Earning between two to four hundred dollars per month, these workers learn to lacerate, snip, and peel layers, soaking bodies in chemicals that are ultimately mummified through a heating process. Each body requires 1,500 hours of labor.

Should these employees be referred to as scientists, engineers, artists, or morticians?

To begin the plastination process, the body or part is fixed in a formaldehyde solution. This allows it to be formed into a desired position and prevents decay. Once dissections are complete, the body or part is submerged in acetone and then frozen, which removes water from the cells. The third step is to place the body in a liquid polymer such as silicone rubber, polyester, or epoxy, which fills the cells with plastic. The final stage is to harden the body by treating it with gas, heat, or ultraviolet light.

The original exhibit, called “Body Worlds,” has been viewed by more than 20 million people, grossing over $120 million. Currently, exhibits are on display in the U.S., Europe, and Canada. These exhibits are the brainchild of Gunther von Hagens, known throughout the world as the inventor of plastination. For approximately ten years starting in 1999, von Hagens owned a plastination company in China with his then business partner Sui Hong-Jin. In 2004, the German magazine Der Spiegel revealed that von Hagens had used bodies of prisoners from China in his displays.

The magazine’s extensive investigative reporting revealed email correspondence with the Chinese factory that produced the plastinated bodies. The correspondence documented proof that bullet wounds had been found in the skulls of seven bodies stored in the factory. In response to this report, von Hagens claimed that he had only discovered the bullet holes in the corpses the week before the story broke.

Since that incident, von Hagens has vowed to use bodies of only consenting donors, foregoing those who are unclaimed. (In the U.S., consent is required to donate your body to an organization or university.) According to reports, von Hagens closed the company in China around 2013 after opening what he has referred to as his “plastinarium” in Guben, Germany, which is currently managed by his son.

His original exhibit has led to at least a dozen copycat exhibits that do not certify that consent from donors was obtained as part of their procurement process. One such exhibit, called “Real Bodies,” is run by Imagine Exhibitions, which procures bodies from a factory in Dalian currently owned by Hong-Jin, who is listed as the CEO of Dalian-Hoffen Bio-Technique Co, Ltd. and director of the anatomy department at Dalian Medical University. These exhibits have toured more than 20 countries, with reportedly over 35 million visitors. There have been multiple reports that Hong-Jin’s company houses primarily bodies of prisoners, including an article in 2018 that reported the findings of the group Doctors Against Forced Organ Harvesting. In this article, president and chief executive of Imagine Exhibitions, Tom Zaller, admits that the bodies provided to his company from the factory are undocumented and therefore, were not consented donations.

Throughout the U.S., permanent or long-term exhibits fill casinos and retail complexes. Imagine casino visitors in Las Vegas eyeing these polished cadavers as they stare outward with empty glances, standing on display at one of the shows headlining the entertainment circuit. Atlantic Station, an Atlanta retail and entertainment development complex with a neighborhood-like feel, features an ongoing exhibit of these androgynous, ageless beings, as do science centers in Florida and California. The viewing dates for these exhibits extend to a year or longer, even as marketers tout the “limited time only” message on billboards and websites.

Once fabricated, bodies are sold to exhibit companies, universities, and anatomical research centers. Websites sell organs and other parts for up to $75,000 each, and a plastinated, exhibit-ready body can fetch up to one million dollars.

To successfully transfer into plastic forms, bodies must be preserved within two days of death. Chinese customs and religious traditions frown upon body donation, leaving the country without consistent sources for anatomy and plastination. In other parts of the world, interest in donation to these exhibits may have increased since the first display was launched over 20 years ago, possibly because of the popularity of the exhibits and the marketing strategy that touts the events as educational.

Yet, the main source for body procurement for these companies (with the exception of the current policy noted by von Hagens for his displays) continues to be unclaimed bodies, which are primarily sourced from China, according to many reports, including this one from the U.S.-based non-profit China Organ Harvest Research Center. According to Chinese law in its “Regulations on Dissection of Corpses” issued by the Ministry of Health in February 1979, only after a human corpse is unclaimed for at least one month can it be classified as such and be used for anatomical studies.

But these bodies wouldn’t be appropriate for plastination, which requires fresh corpses that have not yet been preserved. With no public information available on body donation in China, it’s unclear how the country has met this need, which has been a serious concern for human rights’ advocates. Amid controversies around consent, San Francisco has banned these exhibits, and New York requires consent documentation for each body on display. In 2018, Australia’s Parliament held hearings around banning the exhibits. David Matas, an international human rights attorney and author of several books on organ harvesting, has documented evidence that the Chinese government has been feeding this demand for bodies as they continue to persecute the practitioners of a spiritual practice called Falun Gong.

“There is compelling evidence that practitioners of Falun Gong are killed for both plastination and organ sourcing,” Matas wrote in 2016 as part of submitted testimony to a U.S. House of Representatives joint subcommittee hearing. “The evidence supporting each abuse is also evidence in support of the other abuse. No one in the West has witnessed organ transplant abuse in China; yet a large number have seen plastinated bodies from China on display. Furthermore, plastinated body parts from China have been sold to medical schools and universities throughout the Western world. Plastination gives an immediate, widespread, publicly visible reality to the abuse that the killing of innocents for their organs cannot.”

This past June, an international tribunal on organ harvesting in China released its final judgment and report. The report was led by barrister Sir Geoffrey Nice, who previously prosecuted former president of Serbia, Slobodan Milošević, as part of the UN’s International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia. His work on the current international tribunal found that widespread organ harvesting continues in China despite the country’s 2015 ban on using executed prisoners for organs, with Falun Gong and Uyghurs as the primary sources for these attacks. “The Tribunal notes forced organ harvesting is of unmatched wickedness even compared — on a death for death basis — with the killings by mass crimes committed in the last century. There is justifiable belief in the minds of some or many — rising to probability or high probability — that Genocide has been committed.”

The short form of the report (the full report has not yet been released) concludes with: “Governments and any who interact in any substantial way with the People’s Republic of China, including: doctors and medical institutions; industry, and businesses, most specifically airlines, travel companies, financial services businesses, law firms and pharmaceutical and insurance companies together with individual tourists, educational establishments; arts establishments should now recognize that they are, to the extent revealed above, interacting with a criminal state.” The Chinese Embassy has denied that they were complicit in any of these practices.

If the conclusion of this tribunal and the investigative reports led by journalists, nonprofits, and human rights organizations are true, the magnitude of these crimes against humanity cannot be overstated. Never before in history has the world witnessed such a flagrant display of public evidence, molded by the hands of mortician-sculptors. Never before has the public paid money to witness the standing dead, many of whom are likely victims of state-sponsored genocide.

As these mummified beings stand before curious crowds, perhaps the conversation will shift from entertainment to the ethics of such displays. Beyond the multi-million dollar revenues of these exhibits are grave questions that yearn to be answered, and body tissues and life stories that ultimately belong to the human beings who were the genesis of these sculptures.