Let me start by just naming what I am when I go out in public — a man writing something into a book, who every so often looks up.

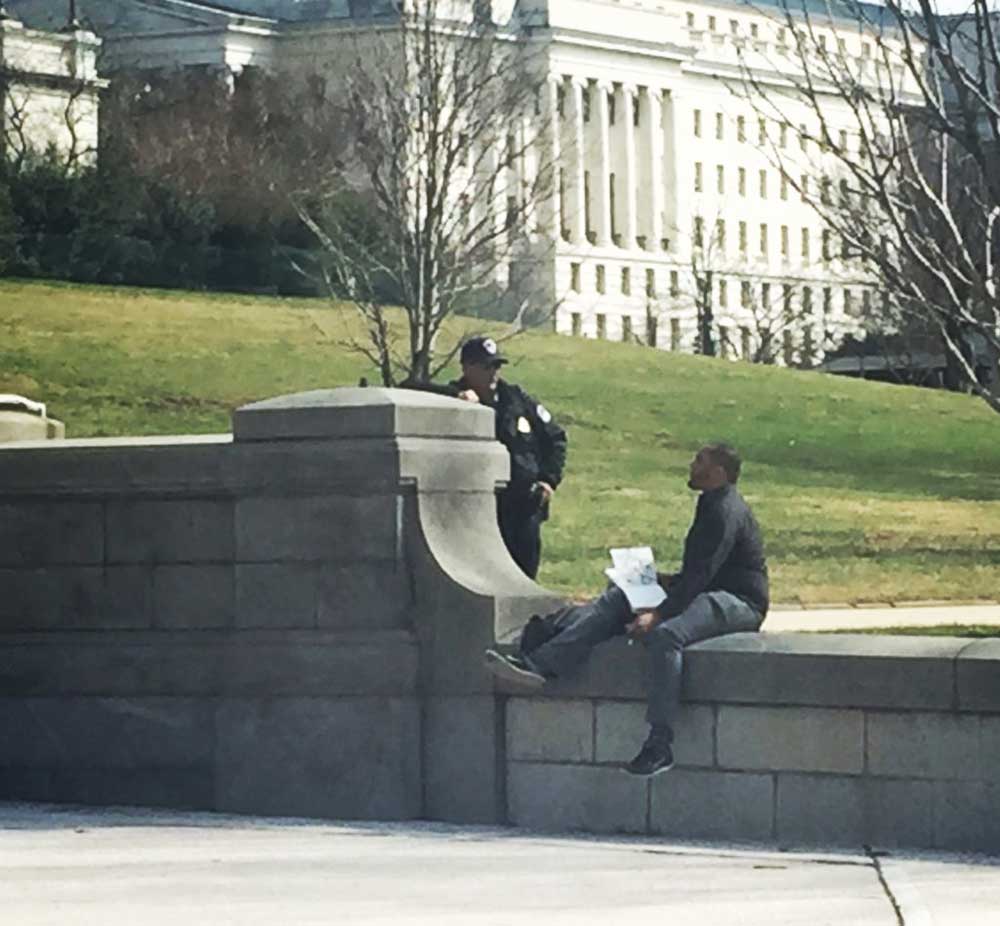

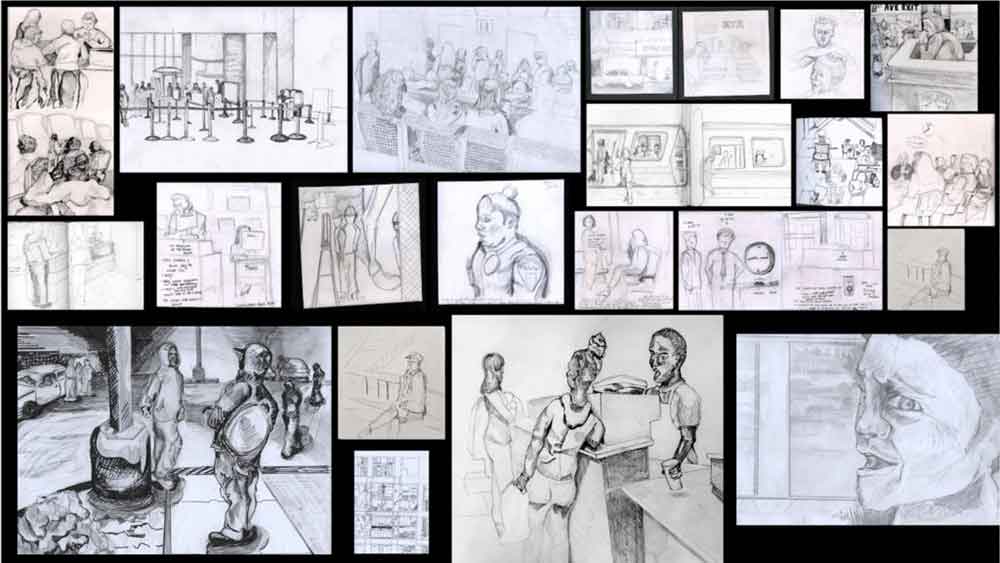

My interdisciplinary art practice evolved from drawings I made while sharing open and public spaces with others. When I drew in my sketchbook, I would often be approached by police, security officials, and passersby who felt the need to see what I was doing. After so many interactions, I felt compelled to document my observational habit so that I could better understand for myself why the docile act of drawing demanded so much attention. My exchange with the U.S. Capitol Police officer in the photograph above suggests that, especially in today’s environment, there are characteristics of being an observer on the streets that agitates authority.

At the time, I had been sketching a man lounging on a bench for less than a minute before the officer came to my side. It is a fool’s errand for me to try to understand exactly and thoroughly why Officer Weatherbee approached me, even though I am inclined to say that he felt the need to assert power over my blackness. I was an easier target than a white male colleague of mine who had been drawing at equidistance. Our motive was to see when and if anyone would interrupt one of us. Officer Weatherbee approached me less than a minute after we started drawing. In the time of the fifteen minute conversation I had with Officer Weatherbee, no one ever approached my colleague to question him. I asked the white guard, “Do I look like a threat?” He shook his head and stated that he just wanted to see what I was drawing. But as a black male, I consider, daily, how extensively all people’s implicit racial biases affect their/our behaviors, so I didn’t find the question to be presumptuous.

Prior to the Civil War, and as recently as the scandal at Abu Ghraib¹, the right to look back at those who hold power has been imbued with racial, sexual, and economic hierarchy. Cultural theorist Nicholas Mirzoeff points out that “‘reckless eyeballing,’ a simple looking at a white person, especially a white woman or person in authority, was forbidden [and] such looking was held to be both violent and sexualized in and of itself — a further intensification of the policing of visuality.” The aftershocks of slavery and Jim Crow laws fomented a loose set of behaviors and actions among those in authority that still affect the observational gaze today. Even when I sit down and draw, even when I hold myself at a distance, more often than not, my sketchbook and my “look” (either my gaze or my physical presence) prompt interactions with security personnel, police officers, TSA agents, and pedestrians. All of these interactions lead me to believe that the right to observe freely is mired in what Mirzoeff calls “a policing of visuality,”² and that the gaze is systematically obfuscated in this era of escalating surveillance and mistrust.

As an artist, there’s a persistent need to align oneself with past trends. Nothing is created in a vacuum and there’s a reference for everything. It wasn’t until I had several interactions and built a catalog of drawings that a colleague brought to my attention a 19th century French ideal known as flâneurism. “Check it out,” he said, “Maybe even wear a beret!” I rolled my eyes at his fashion advice but immersed myself in the archetype’s habits. A simplified definition states that the flâneur can be equated to an idler or a lounger, but a deeper investigation provided me with a more structured code of conduct, one that resonated with my art practice. The flâneur’s actions are revealed in his idleness. He squints, spontaneously takes notes, collects and records urban images, and adjusts his attention to the social disruption and entertainment of his surroundings. Although the flâneur of lore was usually a single, if not a lone, and presumably white male bachelor of a very specific upper-class echelon in Paris, I realized that I was performing the same routines as a contemporary artist.

The cousin of the flâneur is the monocle-wearing dandy, who has satirically appeared on The New Yorker magazine cover for over eighty years as an upper-class cultural onlooker. There have been underpinnings of Black dandies as well, going back to the zoot-suit era of Cab Calloway. This historicity contextualized 21st flânerie for me, while Shantrelle Lewis’s photographic exhibition and subsequent book “Dandy Lion: (Re)Articulating Black Masculine Identity” reaffirmed my insistence to consciously redefine flânerie for myself, a man of color. For Lewis, Black dandyism is read as “a sartorial maneuver used by Black men to confront criminalizing stereotypes, widen conceptions about masculinity, and create a new self-identity for the 21st century.”³ And so I blended my performance, my drawing, and my critique by intersecting flâneurism, dandyism, performance, and race.

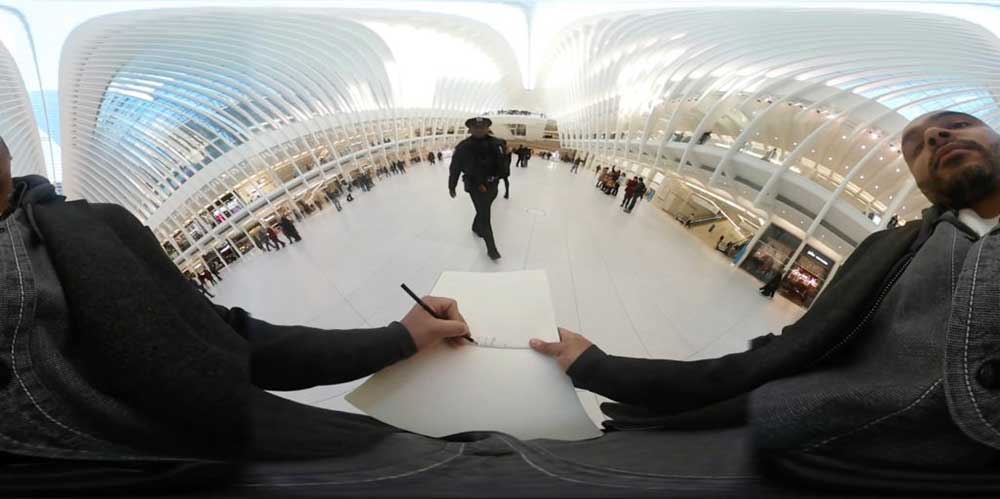

The modus operandi of flânerie let me expose how the act of observation and idle behavior would be met with suspicion. I would go out in public, wear nice clothes, and don wearable technology such as body cameras and audio recording devices, directing friends to take photographs of me while I performed (read: while I drew). Almost always, the cameras were concealed or not in plain sight. In light of the #livingwhileblack hashtag, which is punctuated by implicit racial biases, and the “see something, say something”4 campaign that has come to define our observational habits, I wanted to point to the absurdity of what it means to see and be seen, and exploit the role of the flâneur to clearly show how others would react to my body based upon my gender, race, and profession as an artist. My renegade methods (sketching in a notebook and/or recording with wearable technology) gave me a baseline to investigate urbanity, and my intention was to find spaces where I could stand in contrast to our fast-paced lifestyle and interrupt the movements of people within shared spaces by unobtrusively inserting my body.

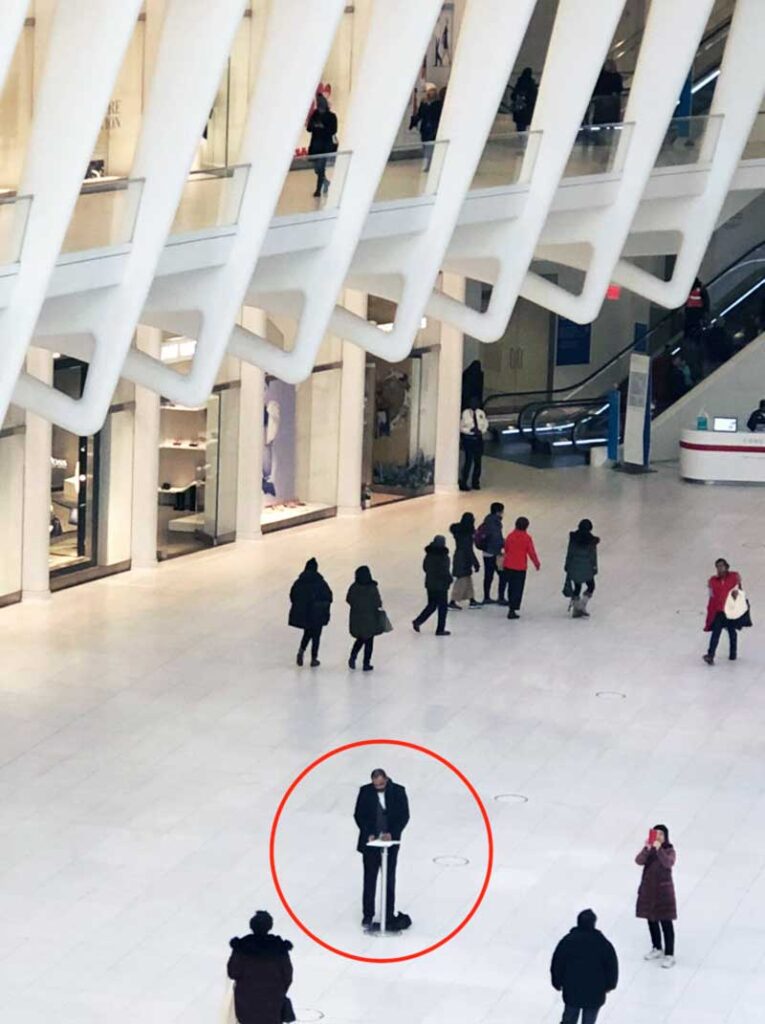

In the winter of 2018, I went to the Oculus Hub in New York City to once again test my methods. I didn’t even have time to turn on my camera before law enforcement approached me. Most of the interactions were with black security guards, but the power dynamics still validated how misguided our trust is in each other. Even when it’s between black men, those in authority seek to suppress the observational gaze. In the span of fifteen minutes, six guards interrupted my attempt to idly stand and draw.

“Sorry brother, you can’t do that here,” one guard said.

“Excuse me sir, can you tell me what are your activities at the moment?” another questioned only minutes later.

“I’m drawing and recording myself draw, I replied.

The security guard parroted my response over a walkie-talkie to others who watched me from afar. SWAT, New York Port Authority Police, Army personnel, and mall security patrol the Oculus Hub. A stanchion, a small spherical camera, and my sketchbook were the three objects that provoked interactions. Some officers thought that the stanchion was an easel that I brought myself. In fact, it was the property of The Port Authority of New York and had been bolted to the ground; they removed it that day.

The performance was a statement about how my experience of seeing stands as an example of “sousveillance.” Sociologist Simone Browne describes sousveillance, a term originally coined by artist-scientist Steve Mann, as “a way of naming an active inversion of the power relations that surveillance entails.”5 For Mann, the phenomenon involves acts of “observation or recording by an entity not in a position of power or authority over the subject of the veillance.” [my italics] And “veillance,” as Browne points out, is “often done through the use of handheld or wearable cameras.”6 It was my intention to observe their actions and I was ready for them to approach me.

The video I shot at the Oculus Hub is not just a documentation of my role as a flâneur (and sousveilleur, to some degree), but also a lens into the extremely sensitive idea of what acts of observation and recording activate in the rest of us. I also want to stress that it is not about technology, for if I had not been wearing the camera, the police would have still stopped me, because I was drawing atop the property of the Port Authority of New York, the stanchion. And if the stanchion had not existed, then my sketchbook would still have activated — as it did with Officer Weatherbee — a reason to interact. By making marks into a book, I was causing trouble — righteously making the pen mightier than the sword, if you will. I feel vindicated by my performances, even though they are in direct opposition of the “see something, say something” rhetoric.

Specific outlines on the Department of Homeland Security’s website insists that when someone sketches, observes, or pays “unusual attention to facilities or buildings beyond a casual or professional interest,”7 then it should be reported. This need to investigate drawing interferes with what artists consider acute observation. Still, a larger theme looms over who gets to enforce the surveillance and what actions should be questioned as unusual, unprofessional, or incendiary.

The performance lends itself to a much larger dialogue about the observational gaze and how surveillance can be traced to stereotypes or unremarkable behaviors in public and shared space. When I take on the act of drawing, it is to signal how idleness provokes an authoritative response. Of course, we are now so entrenched in a system of surveillance that those in authority will scrutinize any suspicious action from afar, resulting in the fact that very little is accepted as normal behavior. What’s more, we live in a system where power has been so seemingly democratized that overseers encourage the surveilled to share in the overseers’ work.

There is no question that in today’s public centers, we’ve sacrificed certain ideals of pedestrian freedom. Communal trust is eroding amid sweeping revisions to security laws in urban environments. Even though these officers are rightfully doing a job to protect civilians, where do we draw a line? Loitering without explanation is also outlined by the Department of Homeland Security as an activity that the public should report for police investigation. Consequently, waiting for a friend in Starbucks, sleeping in the common area of a dorm room, or even barbecuing in a public park provokes not only a police response, but cultural fissures. The ways in which we engage in scrutinizing others in public space have been transformed — and made perverse, really — in this hyper-secured and surveilled age. Above all else, these days, when I go out in public to draw, I’m standing there and saying, “I’m here. Let me be here.”

1 “As late as 1951, a farmer named Matt Ingram was convicted for assaulting a white woman in North Carolina because she had not liked the way he had looked at her from a distance of sixty-five feet. This monitoring of the look was retained in the Abu Ghraib phase of the war in Iraq (2003– 2004), when detainees were forcefully told ‘don’t eyeball me!’” Nicholas Mirzoeff, The Right to Look: A Counterhistory of Visuality (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011), 483.

2 Nicholas Mirzoeff, 482.

3 Lewis, Shantrelle P. Dandy Lion: The Black Dandy and Street Style. New York: Aperture Foundation, 2017.

4 The slogan “see something, say something” was coined by chief executive Allen Kay of the Manhattan advertising agency Korey Kay & Partners one day after the Sept 11th 2001 terrorist attacks.

5 Browne, Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness (Durham: Duke University Press, 2015), 19. The origins of the word surveillance are rooted in the early nineteenth-century French words sur- (over, above) and –veiller (to watch) from Latin vigilare (keep watch). Steve Mann, often considered the design pioneer of wearable computing, substituted sous- (under, below) for sur- when coining the term sousveillance.

6 Steve Mann, “Veillance and Reciprocal Transparency: Surveillance versus Souveillance, AR Glass, Lifelogging and Wearable Computing,” in 2013 IEEE International Symposium on Technology and Society (ISTAS), June 27-39, 2013, 3. http://wearcam.org/veillance/veillance.pdf

7 https://www.dhs.gov/see-something-say-something/what-suspicious-activity