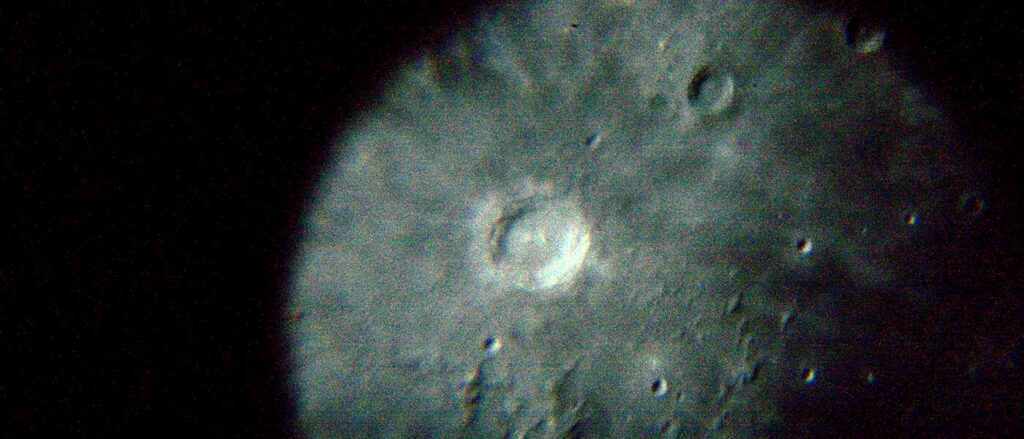

Jenny’s first change, like everybody else’s, was expected. After the requisite meetings with the school’s gender counselor and milk crates of journals full of her weighing the pros and cons of boy or girl, she called her parents Jack and Queenie into the kitchen on the eve of her 11th birthday. They sat tense and watched their only child announce to them, betraying no sign of her fast-pumping heart, that he had decided he would like to be a boy. In a tearful hug the trio came together — not out of relief, for Jack and Queenie would have been happy and supportive had their only child decided to be a girl instead — but because they were caught up in the fluttery pathos that accompanies the first of many such moments for a family. Queenie called her sisters and Jenny’s phone was soon flooded with OMG BOYZ 2GETHER and WOAH, I WOULD HAVE THOUGHT . . . , all of which she ignored by powering down its lithium ion battery and crawling onto the roof outside her bedroom window where the night was just beginning and she could watch the full moon rise over the ridge of mountains like a broken saucer, thin crater lines like spider cracks where it had been glued back together, whole.

The second change, Jenny might have predicted, but nonetheless she tried to avoid it until it was clear there was no other option.

Jenny played basketball with the other boys. Jack showed Jenny how to change the oil and gave him his first car. Jack kept a specialty garage that worked on small engines and did good business because all the other white men in their small New England town trusted him easily. Queenie was a geologist, the first black woman hired by the university to study rocks, and one of her favorite things to say when she came home fuming was, “We can choose our gender, but let a black woman near a seismograph and people lose their shit.” When everyone started pairing off to go to junior prom, Jenny had his mom call the mother of his date and explain that he had come down with strep throat and would be unable to attend. Queenie hung up the receiver and said to no one in particular, “Why bother becoming a boy at all if you’re going to treat a young woman like that?”

It was her mother’s comment that started Jenny thinking that maybe she was wasting her time trying to fit into the decision she’d made. High school passed in a blur of boring afternoons and trysts uneasy and confusing, until finally, she was living on her own, growing out her hair, going weeks without coming home, getting braids and manicures and avoiding Queenie’s text messages. When Jack finally did stop by his son’s apartment one day, Jenny was on her way to work, and they nearly collided in the driveway. Jack got out to apologize to what he assumed to be his son’s girlfriend or attractive female roommate for almost causing a fender-bender. Jenny watched Jack approach in the rearview mirror. He got as far as “My apologies, Miss — ” before he realized he was talking to his son. Jenny stared straight ahead while Jack pieced it all together, then got back in his car and drove away without another word. Jenny hyperventilated a bit, then cried, blew her nose, and drove to work.

It wasn’t unheard of for people to change their minds after the big announcement. Eleven was very young to make a lifelong decision — many in the medical community had long and unsuccessfully petitioned to raise the age of gender declaration for just this reason: too many variables, too many families ripped apart when the choice many parents assumed to be forever crumbles and they’re thrust into years of therapy. All of this is what Queenie said to Jack when he reported back to her that afternoon. She hadn’t been consciously expecting this kind of revision, but once Jack told her the news that their son was now their daughter, she felt a great relief. No more waiting to see what would happen, to see if years of doubts and wondering would be born out. She called Jenny right away and left a voicemail to the effect of we still love you, we will always love you, why don’t you come over for dinner and we’ll work this out.

Jenny did, in fact, leave work ten minutes early to make it to Jack and Queenie’s on time for six o’clock dinner that night. Jack pulled on his mustache nervously, but he used the right pronoun and he was eager to hug when the time called for it, although his body felt tremblingly slight. But somewhere between the pot roast and the apple pie, more effort than Queenie had put into a single meal in a long time since she’d gone up for tenure, Jenny realized she still felt just as trapped as she had on the roof that night before 11.

It was at a bar where Jenny met Zef. They bonded early over the fact that Zef, too, had made changes to his initial declaration of gender. He had become a boy, and was the first white boy she’d ever dated. When she introduced Zef to her parents, Queenie joked about looking in a mirror. Jenny made sure they had lunch out, at a cafe with a patio that bordered the street and where she could glimpse the sky if she leaned out from under the awning. She wasn’t ready to be inside her parents’ home with Zef. After lunch, everyone hugged and went their separate ways: Queenie to her office, Jack to his garage, and Zef and Jenny back to their apartment, where they had recently moved in together.

“Queenie’s happy I’m with a man,” said Jenny, brooding. “She doesn’t know you’re trans, too.”

“Should we tell her?”

“The appearance of straightness!” Jenny said. Her laugh was sharp and barbed. She shrugged, “I don’t know. I like the calm for now.”

When they reached the apartment, Jenny handed Zef her keys and bounced in place.

“You’re not coming in?” he asked. She shook her head.

“I’m too antsy. I think I’ll just go for a quick jog.”

“You’re wearing sandals.”

They both looked down at her strappy shoes that came halfway up her calves. She crouched to undo the tiny silver buckles and handed the tangle of straps to Zef, who took them like a fragile gift. It had been a long time since he’d held women’s shoes, and they intrigued him. Jenny ran to where their cul-de-sac ended in front of the woods, which at that time of day were dark and deep, unpenetrated by the sun. At home, Zef sat on the edge of the bed and held the sandals, feeling their soft faux leather and intricate stitching. Jenny stepped over the curb and climbed a deer path, stepping barefoot over roots and rocks, feeling against her face the wet slap of leaves that held onto yesterday’s rain. In front of the mirror Zef perched on the edge of the bed and laced the straps around his ankles, every third wrap pinching his leg hair. Pausing where the trees began to thin and bare rock gave the impression of a summit with a view of the ridgeline in the afternoon haze, Jenny felt a deep thrumming through the center of her chest down to her toes, her own heart a boulder erratically thumping. A woodpecker startled her with its beat. Zef stood in the bedroom turning left and right, getting a look at his legs sheathed in the delicate straps.

When Jenny came home, Zef said nothing about the twigs caught in her braids, or the scratches on her arms left by the pricker bushes, and Jenny didn’t mention the red lines crisscrossing Zef’s shins. They fucked that night like two cockroaches getting ready for the end of the world inside a black bowl spinning faster than the speed of sound.

What Zef didn’t say to Jenny after they got up and she began watering the houseplants was that he sometimes longed for more options, too; and yet, despite this, he was afraid of losing the Jenny he knew to new changes. So he remained quiet and followed Jenny through the house turning off lights, leaving one incandescent bulb aglow in the hall. Later, when Jenny went to the bathroom, she turned off the light before coming back to bed. Zef knew she’d flipped the switch out of habit, and had he asked her to leave it on she would have apologized and brought the light back. But he didn’t want to admit to being afraid.

Zef didn’t notice the third change until Jenny came home from one of her walks a little taller. Zef was at the stove and Jenny, smelling of pine sap, wrapped her arms around him from behind. Together they stirred the eggplant, purple-black like the cosmos, one of Jenny’s own from the garden. Jenny had always been taller than Zef. But in front of the stove he thought that perhaps her arms hit higher on his chest than usual; her forearms were almost a shelf for his chin to rest on, when normally they were lower down where his binder stopped just above his belly button. He didn’t think much of it then. He leaned back and enjoyed her solidity.

Weeks passed. When Jenny could no longer fit in the yellow bucket seat, Zef took over mowing the lawn. She snapped plastic patio chairs like potato chips. Zef didn’t want to make her uncomfortable, and so he didn’t mention it until one day when he called down from upstairs for a hammer so he could finish the plywood extension for their bed. Standing on the ground floor, Jenny easily handed the hammer to Zef, her head and shoulders stooped against the ceiling. Zef asked casually if she’d noticed anything different. Jenny sat down on the floor, shaking the foundation.

“I don’t know what’s happening to me!” she said. Zef rushed downstairs to comfort her, stopping on the landing so he would be level with her eyes, which were by now the size of saucers.

“It’s okay, it’s okay. There’s nothing wrong with you,” Zef said, stroking her hair.

“Was it something I ate? Are we using new detergent?” They went over everything they could think of as a possible variable: vitamins, new clothes, old clothes, curses, allergies, Mercury in retrograde, fumes, chemical reactions, hormones. But nothing had changed; the skies were clear, planets misaligned as usual, and Jenny had been on the same dose of estrogen for years. The only difference was Jenny.

When Jenny reached the size of the courthouse, she became very slow. She moved like you would expect a giantess to move in a world where everything is very far away and tiny: carefully, every gesture performed at the speed of a grocery conveyor belt. She napped on the lawn because she could no longer fit through the door, and she liked being able to stay with her garden at all hours of the day, watching its miniature vegetables grow and spread. She kept the crows away easily with a wave of her hand.

As her naps became longer, small colonies of lichen grew on her back, her thighs, showing up on a zephyr and taking Jenny over until she was covered in scales of blue and gray, like a stone from the old rock walls that ran across the property. One day Zef was lying out in the sun next to Jenny when he felt a stirring in the ground: Jenny was standing up. Sheets of lichen hung from her legs, clods of dirt and worms rained down as she stretched to her fully impossible height, or what looked impossible now that Zef had grown used to seeing her nestled in child’s pose. Her head was far above the chimney, making it difficult to hear what she was saying even though Zef could see her lips moving around the cave of her mouth. Zef waved his arms until Jenny understood and began the process of kneeling. She brought her head down close to the ground. Zef could almost fit inside her ear.

“What are we going to do?” Zef asked her.

“I don’t know,” she whispered. She shed a tear that watered the garden for a month.

“We’ll figure something out,” Zef said, leaning into her hair. A praying mantis clung to one braid and he flicked it away. “We always have before.”

“It feels different now,” she said. “It takes everything in me not to be a rock.”

“Then you can’t fight it,” Zef said. “Just be a rock. I’ll still love you.”

“But I don’t even know if I’ll be able to love you back. I don’t know if I can still have a family as a rock.”

“I’ll deal. We all will. We love you, and you’ll still feel that.”

Jenny wiped her eyes.

“I hope so. Tell Queenie that I love her. Jack, too.”

Jenny stood up and strode off. Zef watched to see where she would stop — about half a mile away where the highway cut through a deposit of limestone — and then he started walking, taking a brief detour to the dollar store. By the time he got there she was motionless, curled up against the exposed cliff, soaking up the sun with the hint of a smile. With his dollar store spray paint, Zef began marking out JENNY on the part of her hip he could reach from the ground. She gave no indication that she felt the aerosol tickling her rock-hardened skin.

Jack and Queenie nodded and looked grim as Zef told them what had happened. Jack retreated to his garage. Queenie wanted to see where her daughter had petrified, so Zef took her to the cut.

“She makes a fine rock,” said Queenie, shielding her eyes against the sun while gazing up at Jenny.

“She does,” said Zef. To his shock, Queenie leaned in to lick Jenny.

“Igneous or metamorphic?” she asked.

“Sorry?”

“I’m wondering what type of rock my daughter is. Metamorphic is buried and subjected to intense heat and weight. Igneous is explosive force pushing molten rock into hidden places or out the earth’s crust. I’m wondering what sort of pressure she was under.”

Zef and Queenie looked at Jenny closely: great boulders, small pebbles, even imprinted fossils were all mish-mashed into her surface.

“Sedimentary,” said Queenie, putting one hand on her daughter’s thigh, the size of a house and rough to the touch. “Layering over time until she became a mix of something else.”

“Just like she wanted.”

At Queenie’s urging, they opened up a roadside attraction at the cut, a small building attached to where Jenny’s left ankle jutted out of the cliff. Zef ran the front desk and the gift shop. On weekends at 10 and 2, Queenie led informative hikes along the ridge of Jenny’s spine while her students surreptitiously pocketed samples from Jenny’s shoulder blades, and she lectured on the jitters of the seismograph she’d built and its meticulous record of the tiniest vibrations. Queenie was sure the jagged red line left behind was her daughter’s way of communicating. Jack towed an old railcar to the cut and opened a diner next door. Soon Rock Jenny’s grew a reliable crop of old timers who depended on the black coffee and Canadian bacon to keep them going through the work week, and every fall and spring the students would come in loudly at midnight to sober up with waffles. Jack served them all, while Queenie and Zef slept in the back.

Several years passed before the fourth change, in which time Rock Jenny’s had become an established local landmark. When the first tremors began, they snapped the needle on the seismograph. Queenie rushed to the roof of the diner to investigate. She almost fell over from shock when Jenny picked her head up, blinking her lids like tectonic plates.

“I would love some coffee.”

Jack dumped pot after pot into the rain barrel while Jenny stretched out, making sure her limbs weren’t blocking any roadways. She rested her head on her forearms. Zef joined Queenie on the roof.

“Zef, Mom. It’s nice to see you two getting along so well.”

“I’ve missed you, honey,” Queenie said, glancing at Zef. “We all have.”

“I’m sorry I’ve missed so much” said Jenny. Each time she nodded her head it blocked out the sun. She looked sad. “I know you might think I’ve made some selfish choices, but I hope someday you can understand that I’m just seeking my truth, like all of you. Mine’s just been a little bit harder to find.”

Zef shook his head.

“We’ve managed pretty well, considering,” he said, gesturing at the diner, the gift shop, the dirt-packed life they had built together.

“Yes, this place is adorable.” Jenny said, looking around. She slurped Jack’s coffee through a PVC pipe.

“Which is why I’m afraid to tell you,” she said, “but I think I’ve made a mistake.”

“A mistake?” said Queenie.

“Well . . .” Jenny looked up at the sky. “I thought I wanted to be a mountain, but why not the moon?”

“But Jenny. We’re established now. You can’t go.”

Jenny frowned.

“I know. And I don’t begrudge you that. You made do with what you had: a mountain, which when viewed in just the right light looked like a girl. That’s a good angle and you worked it. So did I. But we were only making do. It feels like my whole life I’ve just been making do.”

“But . . . I’ll miss you, sweetie.”

“I’ll keep in touch, Mom.”

Jenny rumbled. She shook so hard that great chunks of her dislodged and hit the ground like meteors. At full height, Jenny could see Canada. She crouched low, and then sprung up into the air, continued rising until she disappeared in the sky. She left behind a crater the size of several swimming pools.

Shortly after, Queenie erected a contraption that allowed her to filter from the air infinitesimally small particles of sand, which she said were tiny pieces of Jenny born on the wind. The sand got caught in a large web of gossamer and collected in a small glass beaker. Sometimes Queenie would pick up the tiny beach of Jenny and give it a shake — she could hear an echo of her laughter that way.

Every couple of months they talked about what to do with the crater — turn it into a pool, a manmade lake with a beach, sell the natural gas rights and profit — but ultimately, they let it sit as a testament to their loss and to Jenny’s many transformations. Jenny’s crater changed on its own in a succession of tiny grasses, followed by weeds, clumps of purple vetch, daisies, and cattails that loved the damp bottom. Eventually baby maples and oaks took root, and it grew into a deep, impenetrable forest.