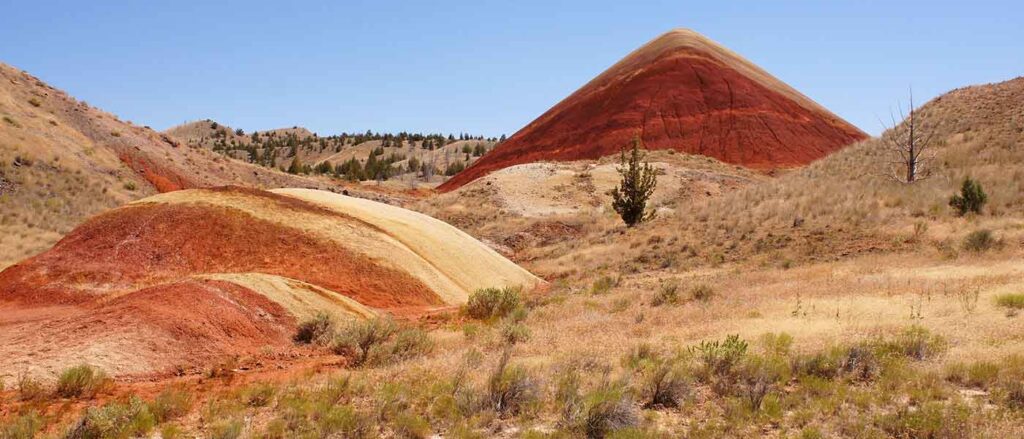

One of our campsites was at the end of a hostile run of unpaved road. We realized how ill-chosen our car was but pressed on, wincing at every scrape and scuff that resonated throughout the Jetta’s frame. When C— parked, I stepped out to see that the splatter shield was twenty feet behind us. The door’s hinges were choked with dust and no longer fit into the frame. Across the river from where we made camp, beyond a wire fence, stood a stratovolcano in miniature. We marveled at its perfect conical shape. Like the Painted Hills, it was a high piling of brilliant red ashes that came from the eruptions of the Oligocene 40 million years ago, with the white silica sprinkled on top. B— was enraptured. “It’s just like Hokusai’s Red Fuji,” she said. “Just a big red mountain. It looks so soft you could take a spoonful. Can we get up there?”

I remember the chalky streak of a plane’s vapor trail, the only blemish in a sky that was deep blue from rim to rim; the reports of rifle shots echoing through the valley; and deep concussions rolling through the grounds. “Wackos setting off pipe bombs,” C— said. The scalding sunlight reduced my body to a stupor and turned my mind into a smithy.

In the trunk were six one-gallon jugs of drinking water, a small mason jar stuffed with a bag of pot, and a large mason jar filled with mescaline. C— decanted the juice, a viscous swill the color of spinach, into a plastic cup and held it before us theatrically. “Okay, I don’t know if I prepared this right. Could do nothing, could destroy our minds.”

“You boiled it for six hours, right?” B— took the cup. “Well, if everything fails, we still have the pulp. I’m down to eat that too. I wanna forget who I am.” She turned to me and said, “I’m warning you, this shit literally smells like puke.”

I didn’t believe her at first, but the odor that affronted me now was unmistakable: sweet and acidic.

My resolve wasn’t strong enough. “I’ll stay sober and be a spotter, loves,” I said. “Better to be safe.”

B— gave me a sweet look. “You sure? You guys are skinny, unlike me; you can probably split what’s left after my half of the dose. But I guess it’s better to be safe out in the desert.”

“It’s more of a semi-desert, really,” I said.

They drank it. Some time passed; the juice didn’t seem to take effect. B— went on to the cactus pulp from which the juice was strained. Its stink was even more offensive, but she gnawed and sucked on the fibrous mush, sauntered over to the back of C—’s car, and profusely vomited.

C—’s face, round and bearded, darkened slightly. His voice, already baritone, was reduced to a morose rumbling. He’d spent our last night in Portland hogging our kitchen with a pot of San Pedro cactus chips about the size of my hand, which boiled for hours on end while we packed. A pall fell on us now, which in hindsight was hard to blame on the disappointment, or on being chemically transported after all. B— sat like a Buddha behind the tent, then walked a circuitous path to the river bank and waded in without a word. (“I’m pretty sure I thought I was a deer,” she later said.)

The river was bustling with trout. C— and I joined B— in the stream, and the fish swam between our ankles. We smoked joints while knee-deep in the water and stared at the massive hills of clay behind the tent, shrubs of cheat-grass spattered on the slopes like poppy seeds. The only way I could mark time was by immersing myself in the waters and then going back onto land. The cotton shirt and booty shorts I wore would dry off completely, and I’d return for another baptism.

“What is that?”

Around the fourth or fifth time I did this, B—, who has sharp eyes, noticed a tiny dimple making its way toward us in the middle of the stream.

“A piece of driftwood?”

“But it’s going against the current.”

It came closer and looked like a dark marble, stately rolling on the water’s surface. In a few seconds we could make out a flat protruding object. It cruised past us.

We knew the John Day fossil beds were rattlesnake country, but we didn’t expect to encounter one swimming up the river.

In the national park’s paleontology center, large painted murals depict mammals, 56 million years ago, grazing, hunting, and fleeing from fissures in the earth and violent eruptions whose ashes cover the sky. Plaster rock walls are helpfully color-coded to denote the corresponding geologic era and the color of volcanic rock it produced, and behind plexi-glass and in drawers are samples of where plants, shellfish, reptiles, and mammals have left their inscriptions. A tortoise shell twice the size of a rugby ball was included. Canned soundscapes of wildlife emanated from tiny speakers mounted in the ceiling corners. The space led us through a narrow curving tunnel of such exhibits.

Thinking about the museum brings to mind the theory of sphere inversion — more properly eversion — in which that shape is turned inside-out while still conforming to the laws of physics. One such proof by the mathematician Bill Thurston shows the outside of the sphere coiling into a tight band, like the cable of an old telephone receiver, with the inside bubbling up through the center. When I am “inside” these exhibits of the past in air-conditioned facilities, I feel as if I were placed “outside” a true contact with them, as if the only way to make the past comprehensible is to place us outside of its continuing influence.

Once, C— drove me on a September Friday evening to Halsey and 16th Avenue in northeast Portland. Sun rays screened through the coils and grids of a power station across the street. A small gathering of a few white men and one black woman were already there.

On May 12, 2010, a 25-year-old black man named Keaton Otis was pulled over on this road by Portland Police’s “Gang-Enforcement” squad because he looked “like a gangster,” as the bureau stated afterward. Keaton was driving a silver Toyota Corolla, which belonged to his mother; perhaps the vehicle appeared to the cops like something above this man’s station. Four police cruisers surrounded Keaton’s car. They put 23 bullets into his body out of 32 rounds fired. The bullet marks in the now vacant brick building along which Keaton parked are still there — I moved my thumb over one of them, felt the roughness of the grains. On the twelfth of every month, a vigil is held in the space where this state-sanctioned murder occurred.

As I studied the bullet marks, a voice behind me said, “I think it happened next to this tree.” I turned to see a bearded white man looking with a solemn face at an ash planted on the sidewalk. Someone had brought a large signboard reading JUSTICE FOR KEATON OTIS. It had a collage of pictures, including one of his father, who had died of a broken heart shortly after his son was taken from him. Another attendant had his phone out, filming for a live stream, and C— and I tried our best to stay out of his shot. Copies of the current issues of Rose City Cop Watch were passed around. The sun sank behind the power station, and a lattice of shadows slid over the vigil. We had an amiable conversation with a pair of anti-racist activists C— knew from another organization, one of whom was a court advocate for juveniles.

“The cops will handcuff kids as young as nine years old, perp-walk them out of school, and drive them to juvie,” she said. “It’s never white kids. And this is for just ordinary school fights or things like that. They bring the cops in as soon as they think they can.”

C— looked at the power station and said, “Kill ‘em all.” He turned his head to us. “The cops, I mean.”

We all turned our heads to mark a police officer who cruised down Halsey on a bicycle. Three months later, the “Gang-Enforcement” police made themselves seen at a Black Lives Matter protest near downtown Portland.

On the third night in the John Day basin, we passed around C—’s pipe and hot-boxed our tent. A few months ago, B— badly injured her back while lifting boxes at work. The management gave her just enough hours to avoid paying benefits. Then came worker’s comp, perfunctory doctor’s appointments, and pills, which did nothing for the pain. She took to popping Vicodin and smoking weed.

“It’s the worst in my shoulder blades, but also in all of my joints,” she said before taking another hit. “It’s so fucked, my body already feels ruined; everything pops when I try to move. The pain never really goes away when I toke, just helps me ignore it.”

I was hard on myself for offering so little to B— beyond emotional support and pitching in on weed. C— at least had the car. I was gone except for weekends. Our ranting against the capitalist system, which escalated from all of us as we got higher, did little material good.

“Sometimes you just kinda freeze and you’re like, entire societies can be taken over and enslaved by a fruit company,” she said, looking at me. “I can’t believe that this is all there is, A—. Why was I born, just to wear out my bones and makes some fucker richer?” C— did a long pull and blew out a flurry of rings.

“Why do I have to live in constant terror of men?” she went on. “When I was waiting in the car for C— to finish his work, some asshole came up and knocked on the window at me. And I’m sorry but he was brown. There isn’t a damn thing anyone can do about this.”

“You had to be the adult in your family for your whole life,” C— said while stroking her thigh. “I never had to cook for my folks, but they bent me straight the second they saw anything queer. They almost broke me in.”

“You ever get a sense that ordinary folks think it’s always been this way,” I said, “and that things will be this way forever, even when you know it can’t go on like this?” I hit the pipe, exhaled, and went on. “Religion used to give structure to the violence of history. In its wake came secular rationality and science with its technological progress and enlightenment. But after the century of massacres, gulags, and the bomb, that’s all been put to bed. So all that’s left is the chaos.”

B— held the lighter askew to the bowl with a practiced air, and the flame lit up her green eyes. I followed the burning cherry’s glow as it passed hands. “I write in my grant applications that I want to tell the stories of the oppressed and that’s all good and liberal, but what does that accomplish other than a cruel mimicry of oppression? How did history ever get so credible when it’s so much fabulation?”

“It’s all just myth,” C— said.

I thought of the glaciers, rivaling the tallest skyscrapers on earth, leveling the rock and baring its strata; of the layers of national crimes we sat on.

Life became heavy again as we drove on Highway 20 back to Portland. Strip malls, motels, fast-food joints, and short-term loan stores passed us by. As civilization accumulated, the world only seemed more abandoned. But the trip had emptied me of ossified thoughts, had opened up a new landscape of thought when the violence in Portland, spectacular and mundane, was threatening us with total despair.

There is a passage from Camus that haunts me: “Blood and hatred lay bare the heart itself; the long demand for justice exhausts even the love that gave it birth. In the clamor we live in, love is impossible and justice not enough.” In his essay “Return to Tipasa,” Camus has come back to his adolescent stomping grounds in Algeria after taking part in the French resistance during the War. He and his comrades had put collaborators to death, and now he wonders whether or not this was evil; the answers evade him. But returning to the sunny Mediterranean gives him respite from fascist Europe, and though he skirts past the issue of himself being a settler in a colonized land, it recharges a deep-seated thirst for justice and love. “I discovered one must keep a freshness and a source of joy intact within, loving the daylight that injustice leaves unscathed, and returning to the fray with this light as a trophy.”

In my own dualism of the hateful city and the semi-desert, I also carry a light with me back home. We can’t abandon history. The past is not past, but a persistent rumor through these objects and places in my life — in the river’s fish, in the vibrant strata and pumice, or in the fossils of the museum and bullet marks in the wall. I have to believe that a dialogue can take place with these rumors, beyond commemorating mass murderers and forgetting their victims.