Busted furniture. Building materials. Car guts. Then a few feet away, loads more: old clothing, broken toys, soiled diapers. Roam farther and memories litter about, whipped by wind – diaries, grocery lists, photographs. Even decomposed bodies of four-legged companions illegally scatter across this land.

This land. A 583-square-mile belt named the Gila River Indian Community, home of the Pima tribe, located south of Phoenix, Arizona. For this pilgrimage I seek a parcel, 0.4% of the homeland hidden in indigenous wilderness.

It’s a settlement Dad once led me to as a boy, its history stretching back to when Nazis invaded Czechoslovakia, Austria, Denmark, France, and so forth. In the same era, Benito Mussolini formed an alliance with Nazi Germany and declared war on the United States. Elsewhere, Imperial Japan invaded the Pacific, overtaking northern Indochina, leading, eventually, to a surprise assault on Pearl Harbor where over 2,000 U.S. military lives ended. From there, tensions raged. And that’s the evidence I search for, decisions from World War II dumped on this land. Butte Camp, as it is remembered, an internment camp for Japanese Americans.

The camp’s whereabouts, however, are forgotten. All I remember is that it’s south of Casa Blanca nested by a plain-looking hill.

My drive follows stretches of canals webbed across the desert frontier. I then fly along an overpass and enter private property, so I flip around, consult a map, reroute the itinerary, and sink deeper into farmland until, thirty minutes on, I’m utterly lost. Shit. Where’s the past Dad drove me to? My rental car scrapes brush, moans through potholes. This section of rezland, a sparse valley of crops, dirt roads, and tumbleweed, is unfamiliar. I’m disoriented in the homeland. Luckily, impatience pulls me over to some strange fellow bathing in canal water.

“Excuse me,” I say, stepping out of the car. “Do you know where I can find the Japanese Internment Camp?” The strange fellow, a pelican-looking bird, flies to a seed-sown field. Not a peep. This is silly, of course, which is why I continue. “My father took me there when I was about eight years old,” I explain. “It’s been awhile and I need to go back.”

The pelican-looking bird flutters a half-a-mile out. Motherfucker.

Down the dirt road is another opportunity, a scraggy jackrabbit who vanishes before my window rolls down. Then a mile later, a quail, so flustered it can’t pick a direction to flee, panics in circles before I’m abandoned for a third time.

No one is helping. No one can. It’s just me, so I must help myself by remembering the route back to Butte Camp. Loosen up. Focus. Dig. What do I remember? Only that Dad warned me to fight back. Fight who? Details are absent.

There’s only one option. Leave no hill unsearched.

Driving around a boulder-spackled hill, zilch. Onto the next mini mountain. Nope. The third hill? A dead-end. There must be a dozen hillsides within close driving distance and an endless horizon pimpled with more. By the fourth hillock I’m done. Then I smell it. The memory. A springtime aroma rushes through a cracked window. Like magic, Dad’s Chevy revs in my mind. He’s driving and talking and warning me to fight the White Man. “They’re going to pull you down,” he advises. “Fight back” — Oh, his clear baritone — “Fight. Back.”

I grip the steering wheel. The accelerator hits the floor. Dust kicks up. I know where to go.

With windows rolled down, orange blossoms return me to boyhood — and if I could return, would Dad be waiting for me there? — to a moment when I stretched outside Dad’s Chevy to snatch blossoms from citrus trees lining the dusty road.

“You’re going to have a tough life,” Dad once said. “Tough because of the White Man.” His warning was weekend propaganda shared between a brown man and his son. And out here, abroad a people-less frontier, Dad was eternally frank and nervous — paranoid even — about the modern era he had brought me into, an era he’d exit early.

Interrupting my thoughts, another jackrabbit, one big sonofabitch, skirts in front of me and sprints as if to lead the way. I drive and chase the jackrabbit, for we are late, two-and-a-half decades too late.

Road-dust streaks a bright blue sky. The sun, slightly hot, slightly tolerable, invigorates the wildland. Parked at the base of the plain-looking hill, fragrant citrus sweeps across the 0.4% of reservation that, in its day from 1942 to 1945, incarcerated 13,000 Japanese Americans.

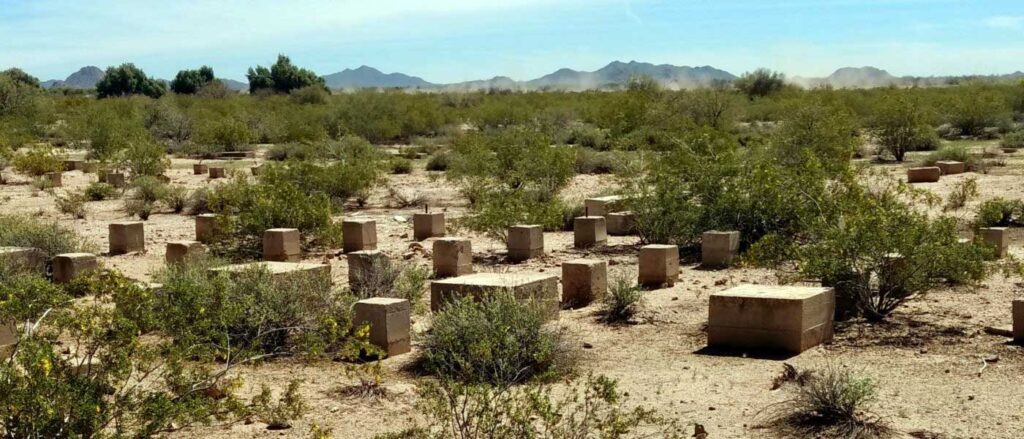

There’s not much left standing, however. Just architectural stains. Where barracks once amassed families during the camp’s three-year tenure, sun-cracked foundations are broken with green growth taking over. Greasewood bushes, weeds, long grasses, and other spring things sprout through asphalt. Gone are the walls, roofs, doors, beds, and families forcibly relocated — mostly from California — to our indigenous homeland. Despite tribal protest, the U.S. Government built the camp anyway. By Executive Order 9066. Signed and issued by President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

But it’s kaput. The barracks. Lookout tower. Staff facilities. Water storage. Mess hall. All 821 structures are missing at Butte Camp.

I discover a pebbled-path nearly healed back into earth. The straightforward track is unnatural in Nature — are humans the only creature codependent on linear direction? — but it’s the exact path thousands obeyed for three years. Children. Mothers. Teachers. Toddlers. Aunts. Scientists. Elderly. Athletes. Preteens. Veterans. Philanthropists. And before he was Mr. Miyagi from The Karate Kid, an eleven-year old Noriyuki “Pat” Morita was hit by the brunt of the Gila River sun. Thousands marched where I do — to fish in the canal, eat at the dining hall, or play at the baseball diamond or small theatre — until a fork traps me. Intersecting directions beg me to choose. This way or the other? Neither suit me. Into the brush this pilgrim goes.

Small stuff stops me: mesh netting fuses with stubborn soil; crowbar claws from dirt like fingers of the living dead; quills sprinkle about that, on closer inspection, are rusty nails; a tin can with a label long gone; a roof tile, just one; a sewage hole (I think) buzzing with mosquito water; and not so small is a mound of big things busted, mostly asphalt. It’s a worthy heap o’ rubble to climb that I decide against as sweat drips off my chest. But if these walls could talk, if indeed that’s what the rubble pile once was, the walls would say they were broken, and that’s what it feels like out here. Not much has changed since boyhood. Then again, how could it?

“The Japanese were sent here without a choice,” Dad had said. “Just like us,” — us meaning the Pima tribe.

“But why?”

What he said is gone; I’d ask his ghost but folklore is an outdated way to lie.

This land, the land of our mothers and fathers, is a dumping ground and human evidence doesn’t wash away so easily in the arid wild.

There are cubic and rectangular-cuboid shaped slabs of cement, some a foot high, others two feet, whose purpose I’m not exactly sure of. I sit and count the columns around me. Forty-seven. The asphalt blocks remind me of the Berlin memorial for Jews murdered during the Holocaust, a sloped grid covered with thousands of coffin-sized, concrete pillars of varying heights, the shortest eight inches, with the tallest towering at fifteen feet. When I visited Denkmal für die ermordeten Juden Europas the year before, I sunk deep into the Berlin memorial and passed pillars taller than the last as if drowning in an asphalt forest. There’s a snapshot of me among the concrete slabs with a mug hesitant to smile and reluctant to frown, as if I was stuck in between. Aren’t those the hours? Stuck in between here and there? In between memorials? In between our parents’ bodies and their grandchildren’s?

Across the Berlin memorial was another, this one dedicated to homosexuals persecuted by Nazis. It’s a massive asphalt cuboid built with an internal video screen broadcasting, at the time, two men kissing.

Two men kissing. I would have been persecuted by the Nazis for that alone, if Dad didn’t get to me first.

The homeland pushes against me. The citrus-scented breeze. A high-noon sun. Bugs, the bzzzzing kind. The concrete slab beneath me. A premonition drifting about.

As Dad warned me to fight the White Man, he brought those battles home. When my teenage sister dated a mullet-draped white boy, for instance, Dad violently threatened my sister’s boyfriend for nearly a decade. What would Dad say when it’d eventually be my turn to date a similar type, sans mullet? Sneaking out, running away, then leaving the house at sixteen, my sister and Dad had years of silence, followed by college graduations, marriage, and then a grandbaby for Dad, his first, which softened most of his rough edges — if only I could have rounded the rest of his corners — but as a preteen I threw a fit for reasons unremembered and Dad revealed there was no guidebook to fatherhood. “Junior, I’m making it up as I go along,” he lamented.

Fatherly temperament and improvisation — the crux of life (and its flaw).

Atop the plain-looking hill is a plaque dedicated to Japanese American soldiers killed during WWII. According to the plaque, over a thousand internees entered military service. An acknowledgement identifies soldiers who sacrificed their lives: “Some names may be unlisted by choice while others were not located. But they are all equally honored.” When Dad and I hiked this hill two-and-a-half decades ago, twenty-three Japanese names were spray painted over. “No respect,” Dad muttered.

Now my father’s age, I study the plaque. The spray paint is gone.

The scars they tended — evicted from homes, forced to sell their possessions and businesses, shipped in trains like cattle, then imprisoned behind barbed-wire for years, only to be released into the American wild, which is more prejudice than the natural wild — some internees returned home to discover their property in the hands of new ownership, while others settled near towns the internment camps hosted. Then the predictable — bigotry, vandalism, gunfire, and brimstone — continued for Japanese American families. Four men, for instance, set off an explosion on the Doi family farm in California in 1945. Despite one of the men implicating the other men, and with a Doi son serving in the U.S. military overseas, a defense attorney argued “[t]his is white man’s country.” All four men were acquitted.

Butte Camp was shut down 10 November 1945. Ninety days later, an atomic bomb annihilated Hiroshima. Three days after, Nagasaki flash-burned, too. Japan surrendered. WWII ended. The scarring I reference: does the White Man, the very same Dad warned me about, stitch the wounds their trickery inflicts?

There’s a panoramic view of the handsome desert. Citrus groves, cotton or alfalfa fields, I can’t tell, whatever is farmed in spring, then more fields beyond that, followed by mobile homes, adobe houses, and villages, Casa Blanca among them. I don’t stay too long because the sun is brutal and so is time. The ripples hit the hardest, ripples of eras that are not my own. The desert does this to me and I don’t know why. It’s as if I’m a pebble skipping across dimensions, exploring histories not belonging to me, and I come out the other side jetlagged in my own time, worn, chipped, going mad I suspect.

Dad guided me through these era-skippings nearly every weekend. Venturing together in the homeland was critical for him. Why? Never mind, because just like the debris out here, I’ve been discarded with the rest of the fatherless.

The desert is a dumping ground. Living involves gestation, birth, procreation, expiration, and, inconveniently, disposal. There’s no alternative to the seasons. Yet, trusty spring is here.

What I mean is that I went to Hiroshima to tie it all together: beneath an ordinary sky, where the atom bomb detonated 1,900 feet above a medical clinic, I imagined hell spewing across the city, unfolding from the epicenter where mothers and children burned in seconds; then the outer ring roared and leveled curves, both natural and manmade, boiling skin with cloth and steel; at last, radiation fell like rain and poisoned everything with a heartbeat. I was not prepared for this. Neither were the victims. But survivors rebuilt the city I wept in. Things grew back. And spring, she helps by covering old things up.

Then again, it’s the young who do that best, even if, and at their peak, it’s temporary relief.

This is an excerpt from a memoir-in-progress titled One Pima Pilgrim, which chronicles pilgrimages to my tribal motherland through four seasons in 2016. This piece is a sprig from springtime.