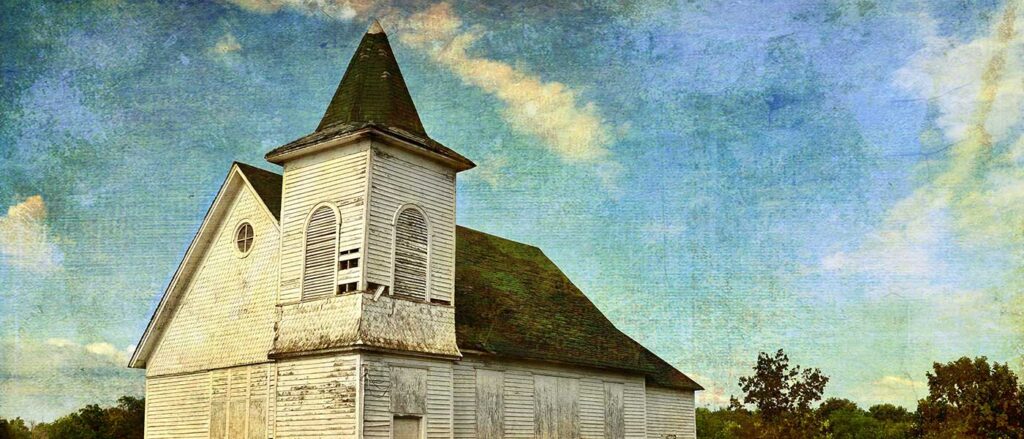

Out past the bridge, past the edge of town where the old houses give way to the stretch of firs that continues for a few miles before dissolving into shrubland, there is a little church, rundown but still standing, on its third or fourth life, passed from one denomination to another. The pastor there now is an older woman, Pastor GJ they call her, although no one could tell you what the letters stand for. She lives in the cottage at the far end of the property, down the hill from the back of the church with its scattering of picnic tables and the loose bricks of a fire pit left over from the previous congregation’s weekly summer clambakes.

Only thirteen people come to Sunday service each week, a few more if there are visitors or stragglers. But that’s thirteen more than Pastor GJ had by the time she left her previous post, five hours and three state lines away, in a town she’d lived in for twenty years, a place she thought was home. In its prime, there had been nearly a hundred members, a real community — a family even — nothing like GJ had experienced growing up in the church. But, like family might, everyone left when the truth came out. And the truth was that she had met someone, and that someone was a woman, and a congregant besides. Gloria, she was called, like something out of a psalm. The two of them had been meeting in secret, stealing moments in the church kitchen together and long afternoons in the parsonage, feeling every bit like teenagers. They spent several tense weeks feigning normalcy at coffee hour, and then cloistering themselves in GJ’s den at night, barely sleeping, trying to decide if it was the right thing to tell the church, exhausted from all the hiding, or from midnight, neither could tell which.

On the Sunday they chose, Gloria had been sitting in the second row in her bright blue blazer, the one GJ loved so much, and Gloria had looked at her up on the chancel like she could do anything, like they could survive anything. They had run through outcomes in their heads — ideal ones, and good ones, and less-than-desired ones — but neither of them had prepared for this. As GJ spoke, up there in front of her congregation, people began shaking their heads, shuffling in their seats, throwing glances down their pews. When the first person stood, it was like a seal breaking, and before GJ could collect herself, before Gloria even thought to turn in her seat and look behind her, half the congregation had begun to walk out, and then more than half. GJ coughed involuntarily into the microphone, and a scream of feedback filled the hall. Some of the congregants turned back to look at her as they left, but their faces were like faces she had once known, each one a picture of disappointment. She tried to continue, but she found herself stuttering like she had as a child, and so she stopped altogether. The room grew quiet as it emptied, and soon it was just the Pastor at the lectern, and her lover in the second row, weeping into the heels of her hands.

Three weeks after her people left her, GJ moved to the little church beyond the bridge, in a state she’d never been to. It hadn’t been the same between her and Gloria after that Sunday morning. They had sacrificed everything for each other, and Gloria couldn’t shake the feeling that maybe it hadn’t been worth it. So the quiet around GJ grew quieter still, and when the texts went unanswered, and the phone didn’t ring, she packed up her old red Outback with her prayer books and her box of stoles, and set out for something else, some slower way of life.

The people who came to her services now were mostly elderly folks, lifelong residents of the town and the miles of unbothered land around it, old men in old denim, arm in arm with their wives, no-nonsense women who nevertheless trembled as they walked. GJ wasn’t sure she’d seen someone under the age of sixty since she set foot in the state, with the exception of one young woman who showed up every few weeks, looking like a child next to the rest of them, but probably in her early thirties. GJ tried to smile extra sweetly in her direction, be particularly pastoral to her when she greeted everyone on their way out. She told herself that she was only recruiting, hoping the young woman would become a regular, maybe bring along a friend or two, grow a younger base, one with children perhaps, generational potential.

But then GJ would switch off the lights in the church, retreat through the overgrown yard to her cottage, find herself something to eat, a peach maybe, a handful of strawberries. Even when she pushed back the curtains as far as they would go, not much light made its way into her rooms, and so, she would often enough end up sitting on her front step, the wood warm against her thighs, peach juice dripping between her knees into the grass as she ate. God was there in those moments, she was sure of it — like a blanket, like the sun itself — but still, a worm of worry found her. That soon everyone in this large, rolling, silent state would take their last breaths, return to the earth, or the sky, and she would be left on her own again.