What makes a country great? Surely the answer doesn’t lie in vast tracts of forest land that have been converted into concrete megastructures, economic prosperity, or the waging and winning of wars. Great countries, in fact, are made from the culmination of various human experiences, traditions, and histories. They are, for better or worse, a collection of the lives that have been built within them in their all-encompassing humanness. In a country like India, there are so many layers and stories stacked one atop the other, and with my work, I am trying to unearth them in a manner that makes my audience pause and take notice.

My practice is rooted deeply in the exploration of themes based on liminality, and the feelings of ambiguity or displacement that occur amongst people that inhabit these transitional spaces. Most often, my projects are focused on investigating the different rites of passage that are found in these in-between worlds, encompassed by the narratives of their inhabitants. Case in point: the visual stories I documented with the nomadic Lamani tribe, in Goa.

These photographs are a documentation of my family’s journey as we relocated our lives from Maharashtra to Karnataka in the month of May: a total distance of 1,052 kilometers or about 654 miles covered in the middle of the nationwide lockdown. We had to cover this distance in one stretch spanning 20 hours of driving, all while juggling a myriad of emotions. There was so much anxiety around the journey itself, the dread of contracting the virus, the shock from suddenly shifting base in the middle of the pandemic, and the fear of not being allowed to cross state borders every time we came across a checkpoint. This sudden displacement occurred because my mother lost her job due to the pandemic, like so many others in our country, and the lease for the house we were living in came to an end, leaving us to pack our things in a rush and make our way towards our hometown of Karnataka while the state borders were still open.

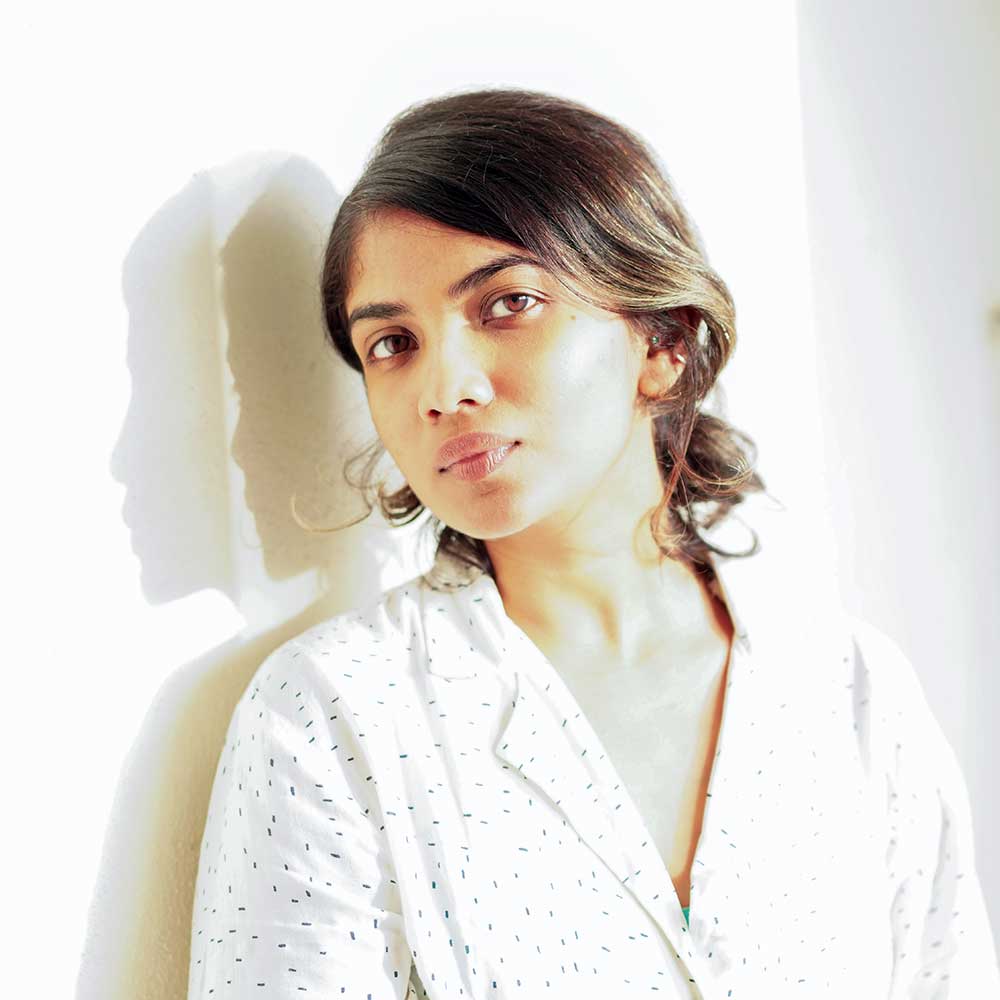

This story is a first-person narrative, nestled in between our initial disillusionment once we realized our freedom and security had been temporarily disrupted and the gradual process of regaining stability. I want to use this story not just to discuss the distance that we covered physically, but also to focus on the emotional journey of moving homes in the middle of a pandemic with its multiple triggers. I want to show you how this journey led me to subsequently take a hard, unwavering, and painful look at what’s happening around me and use this moment of clarity to unpack my privilege as a middle-class citizen of India.

India, like so many other developing nations, has been riddled with a multitude of humanitarian crises for decades now, but the pandemic has played the role of a catalyst in bringing all these issues to the forefront. The biggest of these has been the large scale displacement of its internal migrant workers from the time the pandemic was announced and throughout the strict nationwide lockdown. An estimated 100 million laborers have been displaced or trapped in cities far from home and deprived of work and the chance to sustain their livelihoods. With most transport links shut down, these internal migrants have been forced to make their arduous journeys back home on foot, covering hundreds of kilometers, due to the lack of functional government infrastructure to assist them.

The challenges my family and I faced on our journey are not even remotely comparable to what these internal migrant laborers in my country have been going through in their attempts to get back to their homes. Even though these daily wage workers make up over 20 percent of our country’s workforce; working either in construction, sanitation, and industrial hubs, or taking up other dangerous or low-income jobs; they are still a political “blindspot.” Understanding and observing the differences in both our journeys home made me acutely aware of our privilege as middle-class citizens of India, and many other aspects of this crisis, like the ever-growing chasm between the rich and poor. None of these observations would have come to me as honestly had it not been for our own displacement.

Turning the lens on my parents and myself and holding this space between observer and participant helped me move through this situation more truthfully. It also made me notice and question things I would have normally overlooked, like what it means to truly “belong” somewhere, or what it means to be “from” somewhere. Throughout our journey, and even after, the word safety kept making an appearance. I found myself torn between the hope that we would get home safely and the uncomfortable realization that for so many people in my country, the idea of safety remains merely that — an idea that doesn’t translate into protection. This reminded me of how, throughout history, both safety and the power to control your own narrative have been commodities available only to the privileged.

And so, with these images, I am trying to shed some light on the fragility of belonging, the part our flawed social systems play in this instability, and their colossal unseen effects. I want to facilitate discourse on why it’s important to eradicate these old systems that don’t serve our marginalized communities, that have never served them, and to think toward how to rebuild new ones. To conclude, I’ll leave you with something Olivia Laing said in an article for The Guardian that I resonated with very deeply.

“Art can’t forcibly induce a change in behavior. It is not a re-education pill. Empathy is not something that happens to us when we read War and Peace. Its work, for which art can, however, provide us with radiant materials. Art can’t win an election or bring down a president. It can’t stop the climate crisis or cure a virus or raise the dead. What it can do is serve as an antidote to times of chaos. It can be a route to clarity and it can be a force of resistance and repair, providing new registers, new languages in which to think.”

Please swipe through the images.

All images in this piece ©Vanmayi Shetty.