Picking at the Seeds

I have always felt a visceral lifting in my stomach when I watch my mother peel pomegranates. They are impossible to separate neatly — their insides rip like Velcro-lined jewels, pieces of the white foam-like rind stuck to the seeds. We are queens of the underworld with the seeds in our teeth and my mother’s fingernails stained with the juices. Somehow these fruits, like carmine breasts, hang from the memories of my mother’s family tree. They are an ancient and Near Eastern fruit, what Eve really liked to eat instead of little figs. Maybe it’s because my mother grew up eating them in Iran and brought that with her when she wove her life here, along with gold coins and the Persian New Year.

I wrote a poem about this once, what my mother brought with her to give to me. Among the poem’s images of double pomegranates and hearts, full moons, and a flying mother, there is a stanza about my birth:

Already when she knew me as a stomach moth

With alloy wings, wrapped up in her modern daughter.

Already she had plucked her heart from its humid strings, put it on my pillow.

I appear again in the poem in the last stanza:

My mother shouldered her heart and learned

To windsurf, just in case.

To tell me, This is yours.

To have a daughter, sitting in a moth-eaten closet, her nose

In the perfume of a doppelganger.

The windsurfing is my mother’s idea of how to escape in case the Iranian revolution ever happened again. And the part when I’m a moth in my mother’s stomach isn’t real, but I do have two hearts: my mother’s and my own. So I sit in her closet and lift her silk scarves to my face, breathing in all that is my background. It smells something like pomegranate.

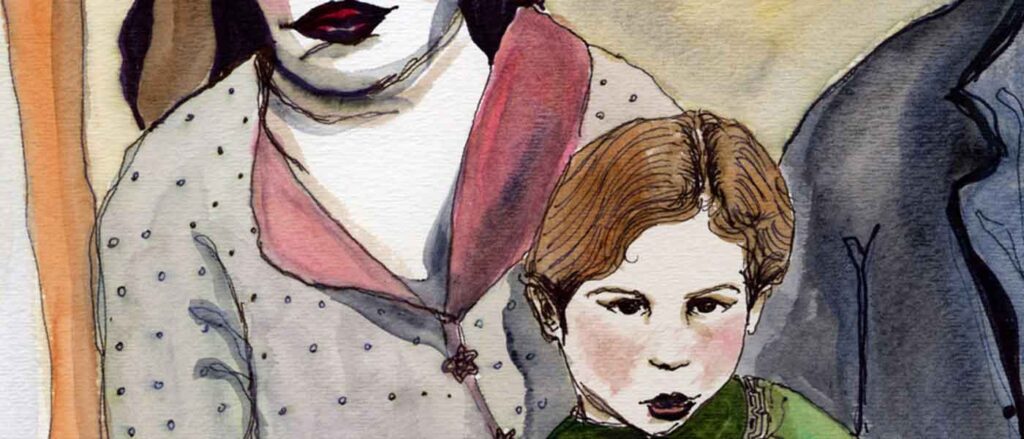

My mother’s mother visited us once in Miami. She left Kurdish carpets and the strong scent of soap in the guest room. I read once that soap can be made of solidified animal fats, and I was sure they still made them like that in Iran. This pig-soap, I was sure, produced that sweet smell, and as a 10-year-old, I was repulsed. Once I went in to say goodnight to my grandmother and she clawed at my pajama bottoms, asking me in Farsi if my underwear was fresh. I hardly speak Farsi and she was hardly anything more than a stranger. We called her Mamanjoon, “dear mother,” but I didn’t know her, and she barely knew my mother, whose name, Elahe, means goddess. The youngest of nine children, my goddess mother was watched by village maids in Tehran to make sure she didn’t drink Coca-Cola while her landowner-father and this mother traveled and lived in a villa by the Caspian Sea. I would never eat a fruit peeled by my grandmother.

We visited Mamanjoon in Iran once, the summer of 2003. Every morning she would offer me and my brother bread and sheep’s cheese, and all we would want was tea. Then she’d smack her chest hard and wail. I brushed her hair gently one afternoon near the end of the trip while she chatted with my mother in loud and happy Farsi. She was nearly deaf and looked so small sitting on the bed in the grand Tehran house. I loved her, distantly and without language. When she died in August of 2005, I was in Germany visiting my other grandmother. And I cried in the shower, dropping a bar of soap so many times. I recently discovered that Mamanjoon had married in her childhood. It came to me how, in Miami, she had loved one of my dolls and taken it to her room. I found the doll on my bed later with a small pair of clumsy Kurdish pants on. There was a small hat too, a strange round cap with colored silk and rough black cloth on the sides. I realized later that it was not made for the doll, but for me.

If the story of my grandmother were a fairy tale, it would begin: “Once upon a girl, a marriage was forced.” The way my mother tells it, there is still a happy ending. But there is no way of knowing that, when you start at the beginning. In time, truths swell like ripe fruit and drop on your head when you half-expect them to. Mamanjoon was 12 years old when she was spotted by a Kurdish tribal leader and his 16-year-old son riding through her village. The son, Bahador, found my grandmother, Saleme, wildly beautiful and wanted to marry her at once, to carry her away on a horse covered in poppy flowers. These are my images — I don’t know where the poppies come from. From what I’ve been told of that Kurdish province, I see sloping hills and, for miles, millions of strawberries dotting the grassy landscape. On one of the occasions when my mother and the other children went to visit their parents in the north, they went for a picnic. My mother, dreamy and restless, wandered off and stumbled upon acres of wild strawberries. She came back to the picnic and everyone followed her to the strawberries. Her father, a tribal leader, named the area after my mother: Elahieh. Even after the revolution, it is still called Elahieh, my mother’s beautiful place: strawberries are as close to poppies as fruit can get to flowers.

Fruit orchards line the properties that my grandmother owned. Now most of that land is in custody of the Islamic Republic of Iran, confiscated by the many bearded mullahs in the revolution. But when I visited, I still had an orchard to wander: a dense garden of trees and small bridges. This last piece of Khazai land is more marvelous than the stories my mother would tell me. Khazai was my mother’s last name. When my grandmother was born, there were no last names. At some point after her marriage to Bahador, they were asked to choose last names to be documented by the Shah. Bahador was traveling and could not contact his wife, but the clear choice of name was Khazai, their tribe. So he had his papers made, confident that Saleme was doing the same. Meanwhile, my grandmother had her papers made in this name: Saleme Ruyani. A respectable, common name, it came from another village and tribe and she enjoyed the sound of it. For the rest of her life, my grandmother was a Ruyani among Khazais.

In Farsi, there is a word for being untrue for the sake of being polite. It is used as a verb — to taroff. When my mother visits her sister’s house and is offered tea, she says no. Even though she’d like some, and she knows she will drink some, she taroffs: it is a little dance. Her sister knows she is taroffing, and will pour her some tea in theatrical protest. And in the middle of the cries for and against tea, my mother will take a sip and it will be over. By offering bread and cheese, and prune jam, and dried quince or chickpea cookies with poppy seeds on top, my grandmother’s heart was tarrofing for me. I said no, but she kept offering.

My mother loves the imaginary Iran she remembers, taroff dance and all. This magical Persia of her childhood is a cross between Paris and strawberry fields forever: when she was a teenager, before she knew English, she would sing the Beatles’ song “Can’t Buy Me Love.” The lyrics go, “Money can’t buy me love, can’t buy me looooove!” And in Iran at the time there was a brand of infants’ powdered milk called “Enfamilo.” So my teenage mother would sing to herself, “Money enfamilo, enfamilooooo!” wondering why Beatles were singing about milk. I went to Iran with the light of these stories dancing in my mind and came back with nightmares for months afterwards. I would wake up in night sweats, sure I had forgotten my scarf and black-cloaked men were after me. I didn’t like eating dusty chickpea cookies and wearing a hot coat in the middle of the summer. My brother had an easier time, and we both love Persian cheese, but we didn’t want to be offered it every time we climbed down the pomegranate tree and entered our grandmother’s house. We wanted to be left alone. According to our mother, feeding someone is a sign of love. In that case, my grandmother was trying to make up for lost time.

Sweet Lemons, Strange Hybrids

My grandmother, Mamanjoon, had little farmer’s hands and terrible handwriting. In her small childhood village, there was only one schoolhouse to fit every age. On the day she met Bahador, she was not in school, but washing Persian carpets in the river with the other village girls. When Bahador and Mamanjoon married, they moved to Tehran and my grandfather sent her to school right away, “to be up to par with him,” as my mother tells me. They even had to hide the fact that she was married, because she was very young, but he insisted she go to school anyway. These young marriages weren’t typical in the city, and if it were a typical young marriage, it would be a traditional family who wouldn’t want their daughter to go to school. My grandparents had their sons and daughters educated in Tehran and later, in the States. My educated mother inherited her mother’s handwriting, so I know I have too — a haphazard, expressive line-drawing of a handwriting that is completely coherent to us — proving to me that this handwriting has nothing to do with my grandmother’s late and little education.

So even if Mamanjoon had not become pregnant a few years into her Tehran schooling and left, her handwriting may have never improved. She might have been asked to leave, or maybe she was happy to do it. My mother refers to Mamanjoon’s first pregnancy as getting her “off the hook — she wasn’t really into school.” Decades later, when Mamanjoon visited us in Miami, she turned to my mother out of the blue and said, “I wish I’d gone back to school.” There was a look on her face that my mother replied to: “Well, you had one of the most amazing rose gardens, you won all those prizes for your horticulture.” Somehow I never heard this before, but maybe knew it all along. I knew my grandmother had loved something, and it’s been hanging over my head all this time. When I was climbing trees as a child, it was there, dangling in front of my face. When I sat under trees all the time, it was there, some of it already fallen and waiting on the ground. Like fruit, round bright fruit like oranges, it was easy to see.

There is a reason our house is filled with strange fruit — oranges that should be sweet, lemons that should be sour — and it has nothing to do with tradition. My grandmother was her own kind of free spirit, living in a space of painful and beautiful paradox: she got married unconventionally early, had ten children out of love, and didn’t concern herself with so many of the cultural customs that governed the people in Iran those days. She planted fruit trees and she liked to create something with them: sour orange and sweet lemon. My mother doesn’t always remember what it’s called: “There is a word, you can look it up, for taking the branch of one tree and putting it on another tree and creating mixed fruit. She did that with fruits that you’re not supposed to mix.”

She worked these unorthodox experiments on citrus fruits and came up with new lines of hybrids. “It’s called hybrid!” And there is something common in Iran called sour orange, a fast-growing version of the leisurely original orange: “So what they did was they would plant a lot of sour orange, and in two years it will have a huge body. Then at that point, she does the transplanting — one fruit on the body of another, but it has to be the same family, like citrus. And on this branch there would be a hybrid fruit, and it would be as good as the orange, but it would be a lot faster growing.” So everybody in Iran did this, but Mamanjoon said, “Why shall I just do orange, when I can do lemon, and I can do sweet lemon, and I can do pomelo…”

My poor mother had to eat these magic and unpredictable fruits: “In our house we had oranges that really were bitter and miserable because of her mixture, but every once in a while there would be these amazing things.” The excitement for strange botany spread in the family: one of my mother’s sisters brought the first kiwis into Iran, and another one tried to bring the first orchids. “And also artichokes — we didn’t have artichokes in Iran, Mahin brought them to plant. So they were aware of these contests, where you take your fruits and the Ministry of Agriculture would give you prizes for the best this or that.” My grandmother just introduced a couple of her hybrids and she won, and was very proud of it. “And she just did that, you know, whenever we had any fruit that had a seed — wherever we were, she would take the seed and put it in her Chanel bags.”

I never associated Chanel with my villager grandmother standing in the orchards and making orange hybrids. But she had Chanel bags, my mother laughs, “And the reason was, people brought presents for my father, or when my brothers and sisters, whenever they felt fancy and they wanted to impress her, like on mother’s day… she had one Chanel suit.” This shook my vague and dreamy version of an Iran of glassy chessboard rice-fields and adobe houses and fading pink metal gates and cows in the street and third-world sandals on everybody’s feet – they had Chanel stores in Iran? Of course not. “Somebody went to France, and my father gave him money and said, ‘Bring the best for her.’”

But my grandmother still did the things she liked to do in her designer clothes: “She had no idea, she would wear her Chanel suit and then go to the kitchen and start messing around and everybody would shout, ‘Don’t do that with your Chanel suit!’” It was the classic black-and-white checkered jacket, with the trimming around. My mother makes a point to note: “It was extra large. I’m just thinking, they must have really let it out! But there was a period when she could fit into all these things when her kids were all grown up.” And she wore it out in her beautiful garden, and put seeds in the pockets of her Chanel suit.

Flowers or fruits? “Oh, anything! If you had a melon, there are a thousand melon seeds, right — she would keep the entire thousand, dry it, and plant it somewhere. And something would come.” She put seeds in her pockets and carried possibilities everywhere. When she visited us in Miami, she planted one of her traveling seeds in our backyard and government officials had to come later to cut our trees because of citrus disease. My mother decided, “Chances are it was her tree that started all this tree disease, because you’re not supposed to bring in seeds — but she smuggled seeds everywhere.” When my grandmother had to leave revolutionary Iran and took refuge in my mother’s apartment in California, she took over the balcony. “She had planters with all sorts of things growing.” And in her suitcases — who knows.

My mother sees her secular Persian mother, somehow, in a story from the Torah: “Somebody is planting a carob tree, and he’s seventy years old. Someone comes by and asks him, ‘Why are you planting a carob tree? It takes seventy years before it gives fruit.’ And he says, ‘So? When I was a child, I climbed carob trees. And I’m planting it for the future children.’” My grandmother’s visit to Miami destroyed all our citrus trees, but I climbed the trees she planted in Iran when I visited her once. And I didn’t even know they came from her pockets and hands: “And this was her thing — you plant seeds! You don’t know which one is going to grow, but if you don’t, nothing will!”

What she would do, in order not to lose the seeds she hoarded, was to make little bundles in her bag where it was tied, and then tie it some more, and then tie it even more: “And whenever we were at customs, they would think they had found someone with drugs. And they would open this, and then underneath there’d be another knot and then another knot and then there’d be seeds. And they were miserable. But it wasn’t against the law to bring seeds.” Anyhow, she found a way to take her seeds to our house.

All throughout Mamanjoon’s life, anybody who ever really felt loving with her would collect seeds and give them to her. Now when my mother asks any of the relatives about Mamanjoon, there is a shift: “They have to spend a few minutes thinking about this woman as a human being, not just in relation to them. Somebody who a book is going to be written about.” My mother says this with new feeling. “The idea alone is enough.” She gives me a brilliant image that comes to her right then, of her mother seeing a seed like a drawing in a science book. They show a thing with a triangle coming to your eyes, and from your eyes to your brain, and there’s a new image of this thing in your mind. “In my mother’s mind, she would see a seed with her eyes, and from her eyes to her brain, it would transform into this little branch, with the flowers, and the plants.”

My mother thinks for a moment, then goes on: “Imagine — I’m a hybrid… you’re a hybrid. How you put two things that are not supposed to go together, together.” My grandmother’s sweet citrus hybrids, from the same family, can be symbols. But they’re also real, the real fruit and the real details that are the most magical. I couldn’t have come up with something better in the best dream, these images my mother never forgets: “In the north, Shomal, it usually didn’t snow. But this was one November and the trees were bright green, with huge bright orange and yellow fruits. And one day, it snowed. And Mamanjoon woke up and saw the snow and she knew that the trees could break from the weight of snow. So she went outside, and she started shaking every tree with her little hands, to make sure that the snow doesn’t break them. And I remember this vision of it, it was white, it was bright green, and it was bright orange.” There she was, small in the middle of it all.

Excerpts from a Hybrid Story by Lilian Mehrel.